You've probably spent hours scouring the web for a tv show script example that looks like what you see on the screen. It’s frustrating. Most of the "templates" you find on random blogs are formatted like stage plays or weird high school essays. Honestly, if you sent those to a manager or a production company, they’d probably toss them in the trash before finishing page one.

Industry standards are weirdly specific. They're non-negotiable.

Writing for television isn't just about the dialogue; it's about the "white space." If your page is a wall of text, you've already lost. A professional tv show script example needs to breathe. It needs to tell the director where to look without actually telling the director where to look. It’s a blueprint, not a novel.

🔗 Read more: Why Berlin's Take My Breath Away Still Defines the Sound of 1986

The Industry Standard Format (And Why It Matters)

There is a very specific reason why scripts look the way they do. It’s not just to be "fancy." It’s about timing. In the industry, one page of a script roughly equals one minute of screen time. This is the "page-a-minute" rule. If your formatting is off—if your margins are too wide or your font isn't Courier 12pt—your timing is a lie. A 60-page script that’s formatted incorrectly might actually be 80 minutes of television, and that’s a nightmare for a line producer trying to build a budget.

Every real tv show script example starts with a Slugline.

INT. DINER - DAY

That’s it. It’s bold, it’s all caps, and it tells the crew exactly where we are. Is it inside? Outside? What's the location? What's the time? You don't need a paragraph of prose describing the "golden hues of the afternoon sun filtering through the cracked window." Just write "DAY." Let the Cinematographer do their job.

Breaking Down the Anatomy of a Scene

Let's look at an illustrative example of how a scene actually flows on the page.

Imagine a scene in a high-stakes legal drama. We’re in a crowded courtroom.

Action lines come next. These should be lean. Mean. Visual.

"MARCUS (40s) wipes sweat from his brow. He looks at the JURY. They aren't looking back."

See that? It’s punchy. Two-word sentences work. They create rhythm. You want the reader’s eyes to fly down the page. If the reader stops to process a complex metaphor, the momentum dies.

Then comes the Character Name. It’s centered. Well, it’s 3.7 inches from the left, but your software handles that.

Below that is the Dialogue.

Marcus says: "I didn't do it."

Simple.

Multi-Cam vs. Single-Cam: The Big Divide

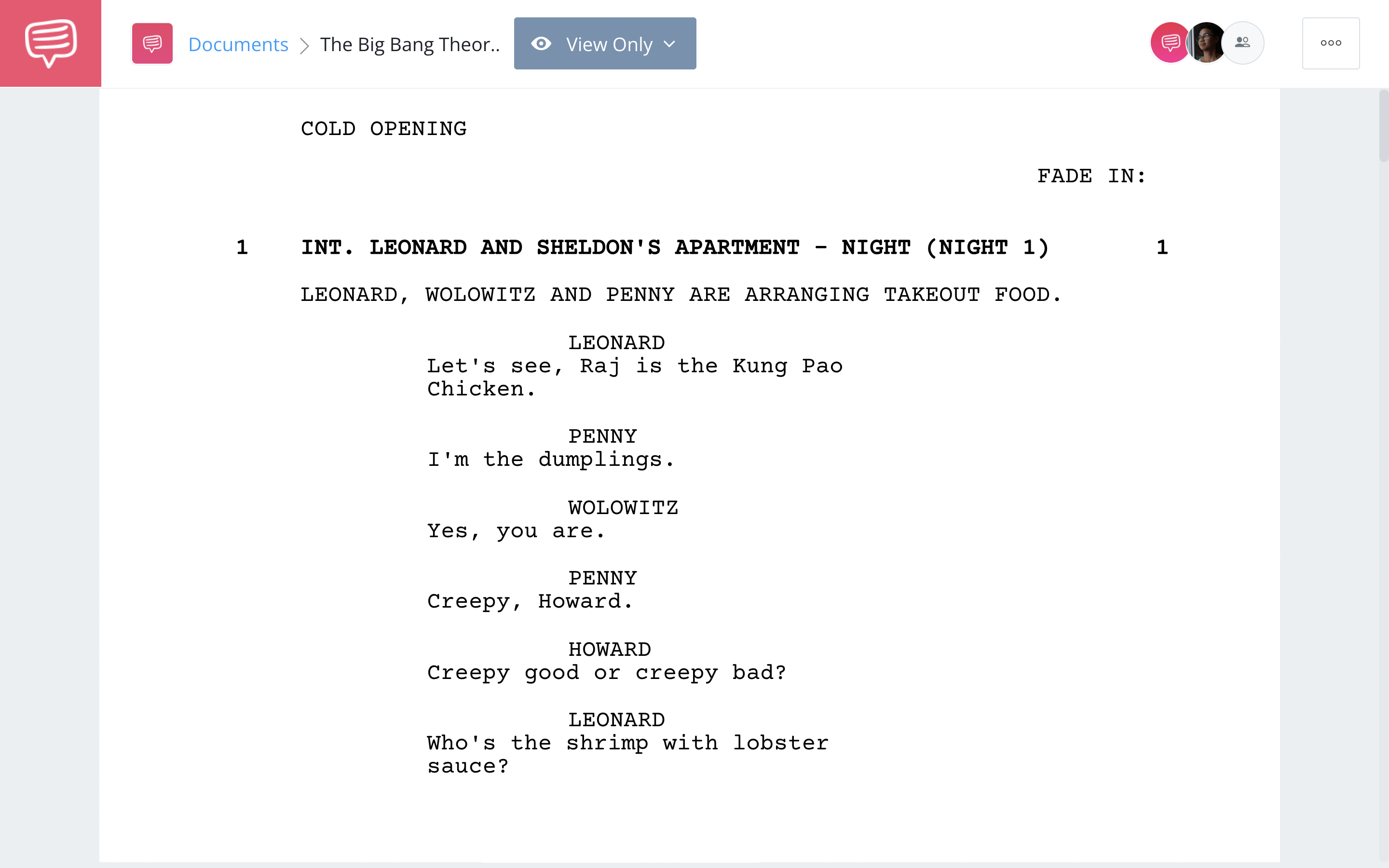

You cannot talk about a tv show script example without acknowledging the massive difference between a sitcom like The Big Bang Theory and a drama like Succession.

Single-cam scripts (the dramas and the "cool" comedies like The Bear) look like movies. They use the standard format I mentioned above. But if you’re looking at a multi-cam script—the ones filmed in front of a live studio audience—the formatting is wild.

In a multi-cam script, the dialogue is often double-spaced. All the action lines are in ALL CAPS. Why? Because the actors and the director need to be able to read their lines from five feet away while standing on a loud, busy stage. It’s purely functional. If you’re writing a pilot, you need to decide which world you’re in before you type a single word. Most newcomers should stick to single-cam formatting unless they are specifically aiming for a traditional network sitcom.

The Pilot Problem: Teasers and Acts

Television scripts are broken down into acts. This is where most people get confused.

A standard hour-long drama usually has a Teaser followed by five acts.

The Teaser is that bit before the opening credits that hooks you. It’s usually 3 to 5 pages. Then you have ACT ONE.

Why do we do this?

Commercials.

Even in the age of Netflix and Max, the act-break structure remains. It creates "cliffhangers" that keep the audience from clicking away. Even if there are no literal commercials, those structural beats help pace the story. If you’re looking at a tv show script example for a show like Grey's Anatomy, you'll see "END OF ACT ONE" centered and underlined. It’s a signal to the reader that a major plot point just landed.

Common Mistakes That Scream "Amateur"

I've read hundreds of scripts. Most of them fail on the first three pages.

One of the biggest red flags? Directing from the page. "The camera pans left to show the gun on the table."

Don't do that.

Instead, write: "A GLOCK 19 sits on the coffee table."

The director knows to show it. You don't need to tell them how to move the camera. It’s insulting to the pros and it clutters the page.

Another one is "unfilmable" action.

"Sarah thinks about her childhood and feels a deep sense of regret."

How do we film that? We can't see "regret" inside someone's head. You have to show it.

"Sarah stares at a dusty teddy bear. She throws it in the trash."

Now we’re cooking. That’s visual storytelling.

Real World Examples to Study

If you want to see how the pros do it, don't look at "transcript" sites. Transcripts are just the dialogue typed out by fans. They aren't scripts.

You need to find "FYC" (For Your Consideration) scripts. These are the actual production drafts released by studios during awards season.

- The Bear (Pilot): Incredible use of white space. The action lines are frantic, mirroring the kitchen environment.

- Stranger Things (Pilot): A masterclass in setting tone and atmosphere without overwriting.

- Succession: Watch how they handle overlapping dialogue and "beats."

Reading these will show you that "rules" are more like guidelines once you're a genius, but for the rest of us, the structure is our best friend.

The Software Question

Don't use Word. Just don't.

I know, it’s tempting because you already have it. But trying to tab your way to a professional tv show script example in Microsoft Word is a form of self-torture. It’ll never look quite right.

Use industry-standard software. Final Draft is the big one, but it’s expensive. If you’re just starting, Fade In is excellent and cheaper. If you want free, Celtx or WriterDuet are great cloud-based options. These programs handle the margins, the character names, and the act breaks automatically. You just hit "Tab" or "Enter." It lets you focus on the story instead of the ruler at the top of the screen.

Beyond the Basics: The "Bible" and the Pitch

A script doesn't exist in a vacuum. Especially in TV.

When you see a tv show script example, you're seeing one piece of a larger puzzle. TV is "long-form" storytelling. Producers don't just want to know what happens in the first 30 minutes; they want to know what happens in episode 50.

This is where the Show Bible comes in.

It’s a document that outlines the world, the characters, and the "engine" of the show. The engine is what keeps the show going week after week. In a procedural like Law & Order, the engine is the crime of the week. In a serialized drama like Breaking Bad, the engine is Walter White’s escalating descent into the criminal underworld.

Your pilot script is your calling card, but your understanding of the show's "legs" is what gets you the job.

Writing Dialogue That Doesn't Suck

Dialogue is the hardest part.

New writers often use "on-the-nose" dialogue. This is when characters say exactly what they feel.

"I am very angry at you because you forgot my birthday!"

People don't talk like that. They're passive-aggressive. They lie. They use subtext.

A better version?

"The cake in the fridge is starting to mold. I'll just throw it out."

The anger is there. The "birthday" is implied. The conflict is sharper. When you study a professional tv show script example, look for what the characters aren't saying. That's where the drama lives.

Final Technical Checklist

Before you ever export that PDF to send to an agent or a contest, do a "sweep."

- Check your Sluglines: Are they consistent? Don't call it "KITCHEN" on page 4 and "MOM'S KITCHEN" on page 10.

- Character Cues: Make sure your character names are consistent. If a character is "DAVE," don't switch to "MR. JOHNSON" halfway through unless there's a specific narrative reason.

- The "Orphan" Rule: Don't leave a single line of a scene on the next page. If a scene ends at the top of page 22, try to edit it so it ends at the bottom of page 21.

- Spelling: Use a spellchecker. Seriously. Typoes in a script suggest you don't care about the details, and television is a medium built on details.

Your Next Steps

Stop reading about scripts and start reading the scripts themselves. Go to the Script Lab or the Black List website and download five pilots of shows you actually like. Don't just read them for the story. Read them for the mechanics.

Look at how they handle transitions.

Look at how they introduce characters. Usually, the first time we see a character, their name is ALL CAPS, followed by a brief, evocative description.

"SARAH (28), a woman who looks like she hasn't slept since the Obama administration."

That tells an actor everything they need to know.

Once you’ve read five scripts, open your software of choice. Don't try to write a masterpiece. Just try to write five pages that look exactly like the ones you just read. If you can master the "look" of a tv show script example, you’ve cleared the first hurdle that trips up 90% of aspiring writers.

Start with a Teaser. Three pages. High stakes. No fluff.

The industry moves fast, and it’s looking for people who can tell a story within the rigid confines of the craft. Structure isn't a cage; it’s the skeleton that holds your story up. Master the skeleton, and the rest is just muscle and skin.

Now, get to work. Open a blank document, set your font to Courier, and write your first slugline. The clock is ticking.