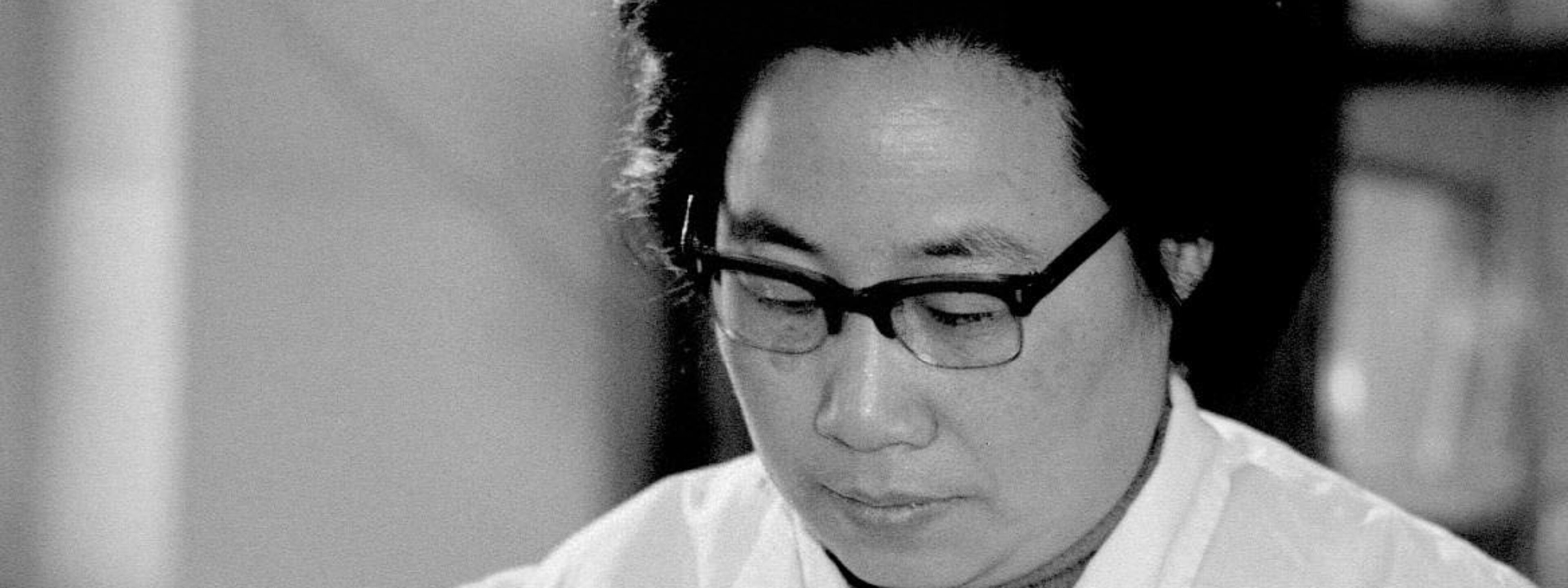

Imagine being a scientist in the middle of a political revolution, handed a secret mission by the government, and told to solve a disease that was killing soldiers faster than bullets. That was the reality for Tu Youyou in 1969. She didn’t have a PhD. She had never studied abroad. In fact, she was later nicknamed the "Three-Nos" scientist because she lacked a doctorate, a medical degree, and membership in any national academy. Yet, she ended up winning the Tu Youyou Nobel Prize in 2015 for a discovery that basically changed the face of global health.

Malaria was the monster. In the late 60s, the parasites causing it had become resistant to chloroquine, which was the standard treatment at the time. It was a crisis. North Vietnam was losing so many troops to the disease that they begged China for help. That’s how Project 523 was born—a top-secret military program named after the date it started, May 23.

The Secret Hunt in Ancient Scrolls

Tu Youyou didn't just look at modern chemicals. Honestly, most scientists already had. They’d screened over 240,000 compounds and found nothing that worked. So, she did something kinda radical: she went backward. She spent years scouring ancient Chinese medical texts, some over 2,000 years old.

She collected 2,000 potential herbal recipes. Her team made 380 extracts from 200 different herbs. It was exhausting, slow work. Eventually, they found a lead in a 4th-century manual called "The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies" by Ge Hong. It mentioned Qinghao (sweet wormwood) as a treatment for "intermittent fevers."

But here’s the weird part.

Initially, the extracts didn't work. The results were inconsistent.

✨ Don't miss: Horizon Treadmill 7.0 AT: What Most People Get Wrong

Tu Youyou went back to the text and noticed a specific instruction: "Soak a handful of qinghao in two litres of water, strain the juice and drink it all."

She realized they were boiling the herb and destroying the active ingredient with heat. She switched to an ether-based solvent that boiled at a much lower temperature. It worked. In 1971, they had a compound that was 100% effective against malaria in mice and monkeys.

Taking the Ultimate Risk

Before you can give a new drug to patients, you have to know it’s safe. Tu Youyou didn't wait for a committee. She volunteered to be the first human subject. "As the head of this research group, I had the responsibility," she said later. She and two colleagues took the extract themselves to prove it wasn't toxic.

Once they knew it was safe, they headed to Hainan Island. It was a tropical hotspot for malaria. They tested it on 21 patients. Every single one of them recovered.

🔗 Read more: How to Treat Uneven Skin Tone Without Wasting a Fortune on TikTok Trends

The Long Road to the Tu Youyou Nobel Prize

Even though the discovery happened in the early 70s, the world didn't really know about it for a long time. China was isolated. The work was kept secret. When it was finally published in 1977, it was under an anonymous collective name.

It took decades for the World Health Organization (WHO) to fully embrace artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) as the primary treatment for malaria. Once they did, the impact was staggering. Mortality rates for malaria plummeted, especially in Africa and Southeast Asia.

- 1967: Project 523 begins.

- 1971: Tu Youyou isolates artemisinin using low-temperature extraction.

- 1972: First successful human trials in Hainan.

- 2011: Tu wins the Lasker Award, often a precursor to the Nobel.

- 2015: The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is officially awarded to her.

Winning the Tu Youyou Nobel Prize wasn't just a personal win. It was a massive validation of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) integrated with modern pharmacology. She famously called artemisinin "a gift from traditional Chinese medicine to the world."

Why It Still Matters Today

We aren't out of the woods yet. Parasites are starting to show resistance to artemisinin in parts of Southeast Asia and Africa. This is why her story is more than just a history lesson. It’s a reminder that we need to keep looking in unexpected places for the next big breakthrough.

💡 You might also like: My eye keeps twitching for days: When to ignore it and when to actually worry

The Nobel committee recognized her because her work led to the survival of millions of people. It’s arguably one of the most significant pharmaceutical interventions of the last half-century.

If you’re interested in how this affects current health policy or want to understand the science of plant-based medicine better, here’s what you can do next:

- Check the latest WHO Malaria Report to see how ACTs are performing against new resistant strains.

- Research "ethnobotany" to see how other scientists are currently using ancient texts to find modern cures for diseases like cancer or Alzheimer's.

- Support organizations like the Against Malaria Foundation, which distributes bed nets and treatments in high-risk areas.

Tu Youyou’s journey proves that sometimes the future of medicine is hidden in the past. You just have to know how to read the instructions correctly.