You’re standing on the sand at Waikiki. The water is turquoise, the surfers are catching waist-high peelers, and everything feels solid. But Hawaii has a secret history written in salt and debris. When people talk about tsunami wave height Hawaii, they usually picture a Hollywood-style vertical wall of water. The reality? It’s much weirder. And honestly, way more dangerous.

Most people think a 10-foot tsunami is like a 10-foot surf wave. It isn't. Not even close.

🔗 Read more: Mexican Hot Chocolate Cookies: Why Your Spices Probably Aren't Working

A surf wave is a surface event. A tsunami is the entire ocean moving. Imagine the difference between a cup of water being splashed at you and a whole bathtub being dumped on your head. Now, imagine that bathtub is the size of the Pacific.

What People Get Wrong About Tsunami Wave Height Hawaii

When a warning goes out, the first thing everyone asks is "How big?" But "height" in the context of a tsunami is a bit of a moving target. Scientists use terms like "amplitude" and "run-up," and if you don't know the difference, you might stay in the splash zone when you should be at high elevation.

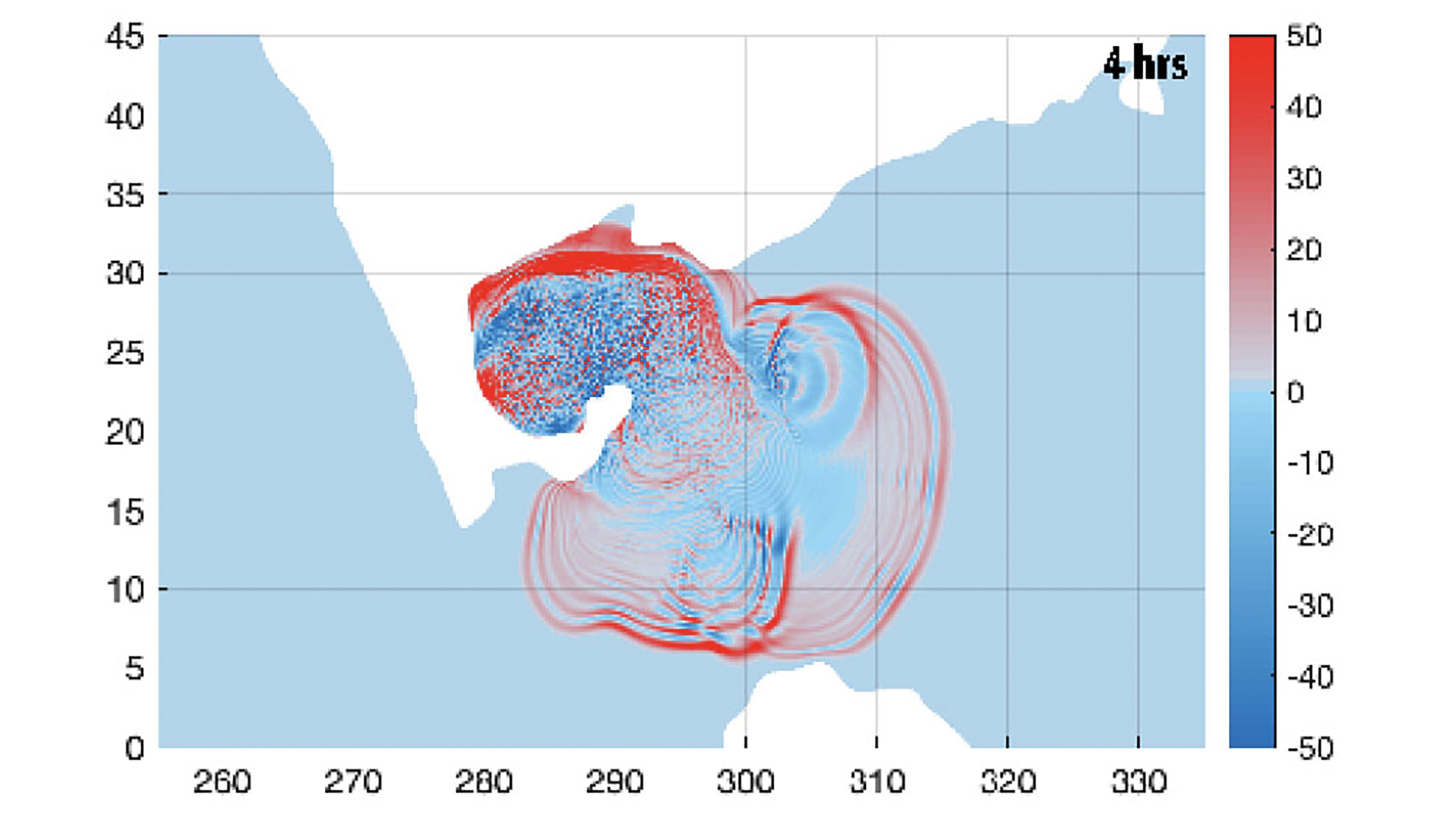

Amplitude is the height of the wave above the normal sea level as it travels through the open ocean. In the deep sea, a tsunami might only be a foot high. You could be on a boat and not even feel it. But as it hits the shallow shelf of the Hawaiian Islands, that energy has nowhere to go but up.

The Run-up Reality

Run-up is the number that actually matters to you. This is the maximum vertical height the water reaches above sea level once it hits land.

- 1946 Aleutian Tsunami: Recorded run-ups of 55 feet at Pololu Valley on the Big Island.

- 1957 Andreanof Islands Tsunami: Saw a staggering 52-foot (16m) surge on Kauai.

- 1960 Chile Tsunami: Hit Hilo with a 35-foot wall of water that froze the town clock at 1:04 AM.

These aren't just waves. They are surges. They look like a tide that won't stop rising, or a "bore"—a churning wall of debris-filled water that moves faster than you can run.

Why Hilo Is a Tsunami Magnet

If you look at the history of Hawaii, Hilo gets hammered. It's kinda tragic. The bay is shaped like a funnel, which is basically the worst-case scenario for a tsunami. As the water enters the narrowing bay, the energy is compressed, forcing the wave height to skyrocket.

In 1960, the tsunami from Chile took 15 hours to reach Hawaii. People had time. Some even went down to the shore to watch. That was a fatal mistake. The third wave was the killer, a massive bore that pushed nearly 240 hectares of water inland.

The Mystery of the 500-Year Mammoth

Scientists like Rhett Butler from the University of Hawaii have found evidence of something even scarier. In a sinkhole on Kauai, they found a massive pile of marine debris—sediment, shells, and coral—nearly 30 feet above sea level.

👉 See also: Why November 11 Matters Way More Than Just a Day Off

Carbon dating suggests this happened about 500 years ago. This wasn't a "normal" tsunami. It was likely three times the size of the 1946 disaster. We're talking about a wave height in Hawaii that would overtop most coastal infrastructure today. It's a reminder that the "worst on record" isn't necessarily the worst possible.

How We Measure This Stuff Today

We've come a long way from just looking at watermarks on trees. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Honolulu is the nerve center. They use a mix of:

- DART Buoys: Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis. These sit on the ocean floor and measure pressure changes. They can detect a tsunami only millimeters high in the open sea.

- GNSS Satellites: Researchers like Tony Song at NASA have been using GPS to measure how the seafloor actually moves during an earthquake. If the ground slips 30 feet, that’s a lot of water being displaced.

- Tide Gauges: These are located in harbors and give real-time data on how the sea level is fluctuating.

Survival Isn't About the Height

Honestly, focusing solely on the predicted height can be a trap. A 3-foot tsunami sounds small, right? But a 3-foot tsunami can have enough force to move cars and destroy piers. The water is heavy. It's full of "stuff"—wood, cars, pieces of houses—that acts like a giant abrasive.

📖 Related: Homemade Olive Oil Mayonnaise: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Steps for Hawaii Residents and Visitors

If you're in Hawaii, you need a plan that doesn't rely on a "perfect" prediction.

- Know Your Zone: Use the Tsunami Aware tool. Enter your address. If you're in the red, you need to be ready to move the moment a warning is issued.

- Identify Your High Ground: You don't need to go to the top of a mountain. You just need to get out of the inundation zone. In many places, this is just a few blocks inland or up to the 4th floor of a reinforced concrete building.

- Watch the Water: If the ocean suddenly recedes—leaving fish flopping on the reef—don't go out to look. Run. That's the "trough" of the wave, and the "crest" is minutes away.

- The First Wave is Never the Only Wave: Tsunamis are a series of waves. Sometimes the second or fourth wave is the largest. Wait for the "all clear" from Civil Defense before you even think about heading back.

The ocean is part of the beauty of the islands, but it’s a powerful neighbor. Respecting the potential for extreme tsunami wave height in Hawaii isn't about being scared; it's about being smart.

Next Steps for You

Grab your phone right now and look up the evacuation map for your specific area. If you're staying in a hotel, look at the back of the door—they usually have the evacuation routes posted there. Don't wait for the sirens to find out where the "blue line" of safety is.