Ever looked at those chaotic lines on a weather map during hurricane season and felt like you were staring at a bowl of neon pasta? We call them spaghetti plots. Most people think those lines are just different guesses, but they’re actually the output of incredibly complex math trying to solve a puzzle that changes every second. Tropical storm prediction models aren't just one "thing"—they are a massive, global network of supercomputers screaming at each other about air pressure and water temperature.

The truth is, even the smartest PhD at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) can't tell you exactly where a storm will land ten days out. Physics won't allow it. It’s chaotic. Basically, if a butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil, it really might change whether a Category 4 hits Miami or veers into the empty Atlantic. We’ve gotten way better at predicting the track, but intensity? Honestly, that’s still a huge headache for the scientific community.

The Two Big Dogs: GFS vs. ECMWF

If you follow weather Twitter—which is a wild place, by the way—you’ve heard of the "American Model" and the "European Model." These are the heavyweights. The GFS (Global Forecast System) is run by NOAA here in the States. Then you’ve got the ECMWF, which is the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

✨ Don't miss: USB to USB Cable: Why Connecting Two PCs Isn't as Simple as You Think

For years, the Euro model basically dunked on the GFS. It famously nailed Hurricane Sandy’s bizarre left hook into New Jersey in 2012 while the GFS was busy dreaming the storm would head out to sea. Why? It comes down to data assimilation. The Euro model traditionally had a better way of "starting" its math by more accurately weighing current satellite data. However, the U.S. has poured billions into upgrades recently. They launched the GFSv16 and now v17, using the FV3 (Finite-Volume Cubed-Sphere) dynamical core. It’s a lot faster now. It’s more granular. But the rivalry is still there, and during any given storm, you’ll see meteorologists arguing over which one is "handling" the ridge over the Atlantic better.

What’s actually under the hood?

Think of a model like a digital grid of the entire planet.

The computer divides the atmosphere into millions of little boxes. Inside each box, it solves the primitive equations—massive calculus problems involving fluid dynamics and thermodynamics. We’re talking about $F = ma$ but for wind. The smaller the boxes, the "higher" the resolution. A high-resolution model might see a small island or a specific mountain range that a low-resolution model just ignores. If the model ignores a mountain, it won't realize the storm's circulation is going to get shredded when it passes over land. That’s how you get a "forecast fail."

Why Intensity is the Final Frontier

Tracking where a storm goes is a "steering" problem. If you put a cork in a river, you just need to know which way the water is moving to know where the cork goes. That’s the track. But intensity? That’s about the internal engine of the storm.

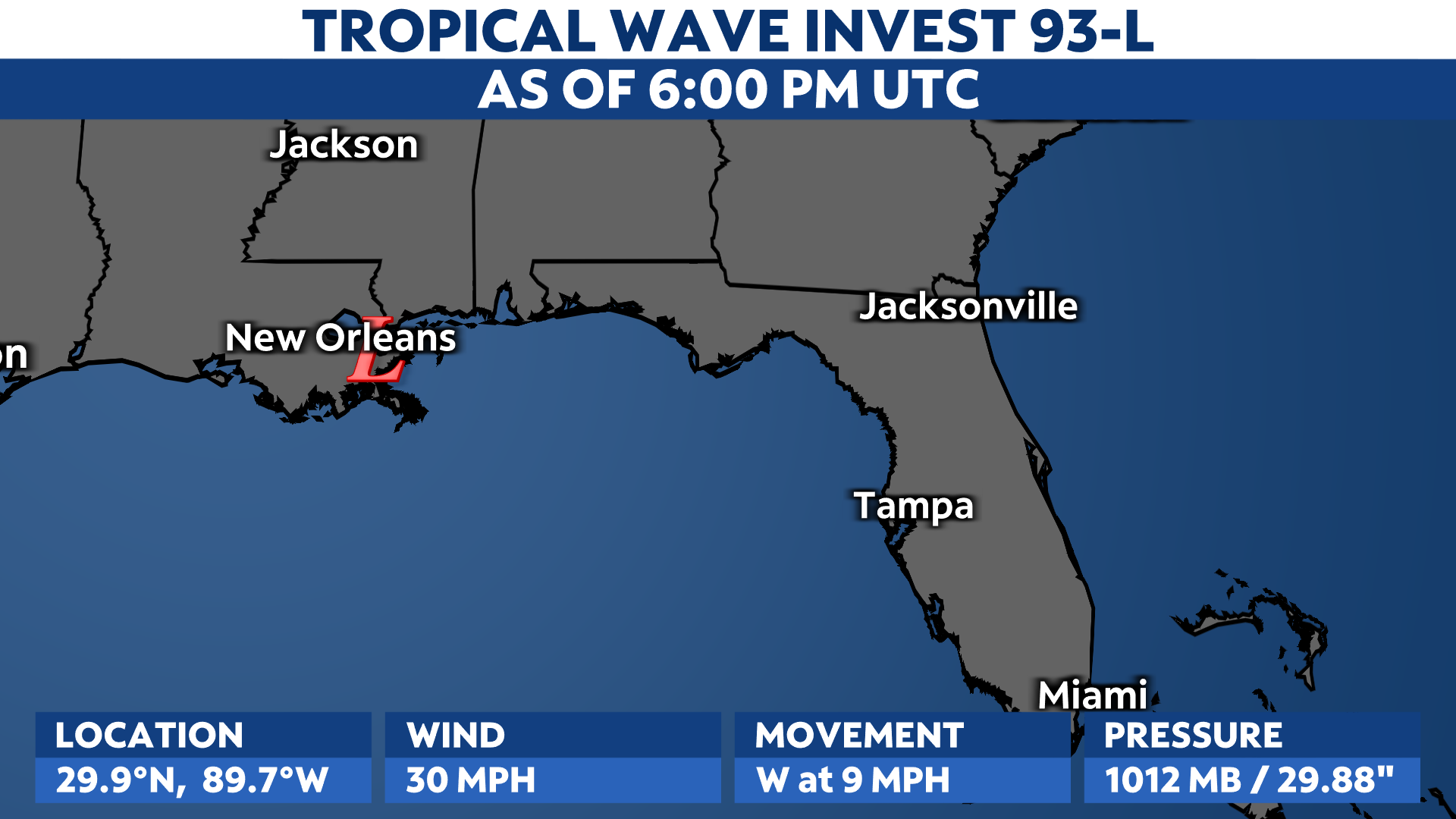

We use specific "regional" models for this, like the HAFS (Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System). Unlike the global models that look at the whole world, HAFS zooms in. It looks at the "eyewall"—that terrifying ring of clouds around the center. It tries to calculate how much heat the storm is sucking up from the ocean. If there’s a pocket of warm water (like a Loop Current eddy in the Gulf of Mexico), the storm can undergo "Rapid Intensification." This is the nightmare scenario for emergency managers. It's when a storm jumps from a Category 1 to a Category 4 in twenty-four hours. Honestly, the models still struggle with this because the data inside the storm is so messy.

We drop "dropsondes" from planes—little sensor packages—directly into the eyewall to get real-time data. But even then, the ocean-atmosphere interface is incredibly hard to simulate.

The "Ensemble" Trick

You've probably noticed that one model run might show a storm hitting New Orleans, and the very next run six hours later shows it hitting Tampa. It’s frustrating. To fix this, scientists use ensembles. Instead of running the model once, they run it 30 or 50 times. Each time, they change the starting conditions just a tiny bit.

- If all 50 runs end up in the same spot, meteorologists have "high confidence."

- If the lines look like a spiderweb exploding in every direction, the confidence is low.

- The "mean" or average of these lines is usually more accurate than any single "deterministic" run.

This is why you should never trust a single "spaghetti" line you see on a random Facebook post. If it’s an outlier, it’s probably wrong. Focus on the "cone of uncertainty." That cone represents where the center of the storm is likely to be 60% to 70% of the time based on historical errors. It doesn't tell you about the size of the storm, just where the middle might go.

Machine Learning is Crashing the Party

In just the last two years, AI has completely flipped the script. Companies like Google (GraphCast) and Nvidia (FourCastNet) have released tropical storm prediction models based on machine learning rather than traditional physics equations.

It sounds like sci-fi, but it’s real. Instead of solving calculus, these AI models look at 40 years of past weather data and say, "Usually, when the clouds look like this and the pressure is that, this happens next." They are shockingly fast. A traditional supercomputer takes an hour to run a 10-day forecast; GraphCast can do it in under a minute on a single desktop-grade machine. In 2023 and 2024, these AI models actually outperformed the Euro and GFS in several track categories. They aren't perfect yet—they tend to "smooth out" the extremes, meaning they might miss the peak intensity of a record-breaking storm—but they are the future.

How to Actually Use This Info

Most people get overwhelmed by the data. If you’re living in a hurricane zone, you don’t need to be a weekend meteorologist, but you do need to know who to listen to.

- Stop "Model Hogging": Don't go looking for the one model that shows the storm missing you just to feel better. That’s "confirmation bias," and it’s dangerous.

- Trust the NHC: The National Hurricane Center forecasters are the "human filter." They look at the GFS, the Euro, the UKMET, and the AI models, and then they use their decades of experience to create the official forecast. Their "Official Forecast" almost always beats any individual model over the long haul.

- Watch the Trends: Don't freak out over one update at 2:00 PM. Look at whether the models are shifting consistently in one direction over 24 to 48 hours.

- The "Dirty Side" Matters: Remember that the track is just a line. Tropical storms are hundreds of miles wide. Even if the model says the center stays offshore, you might still get the "right-front quadrant"—the part of the storm with the highest surge and most tornadoes.

Moving Forward

The tech is moving fast. We’re getting better at "seeing" through the clouds with new microwave satellites, which helps the models start with better data. We’re also seeing more "coupled" models that simulate the ocean and the air at the same time, which is key for intensity.

If you want to stay ahead of the next big one, start following the National Hurricane Center’s Tropical Weather Outlook daily starting in June. Learn to read the "Key Messages" they post. They translate the math into English. Use sites like Tropical Tidbits if you want to see the raw model data for yourself, but always keep a grain of salt handy. The models are just tools, not crystal balls.

Invest in a high-quality weather app that uses ECMWF data—many free ones just use the standard GFS because it’s free for developers to access. Understanding the "why" behind the forecast won't stop the wind from blowing, but it'll definitely stop you from panicking over a "spaghetti" line that doesn't matter. Over the next few years, watch for the integration of AI into your standard weather apps; that's where the most significant jumps in lead time are going to come from.