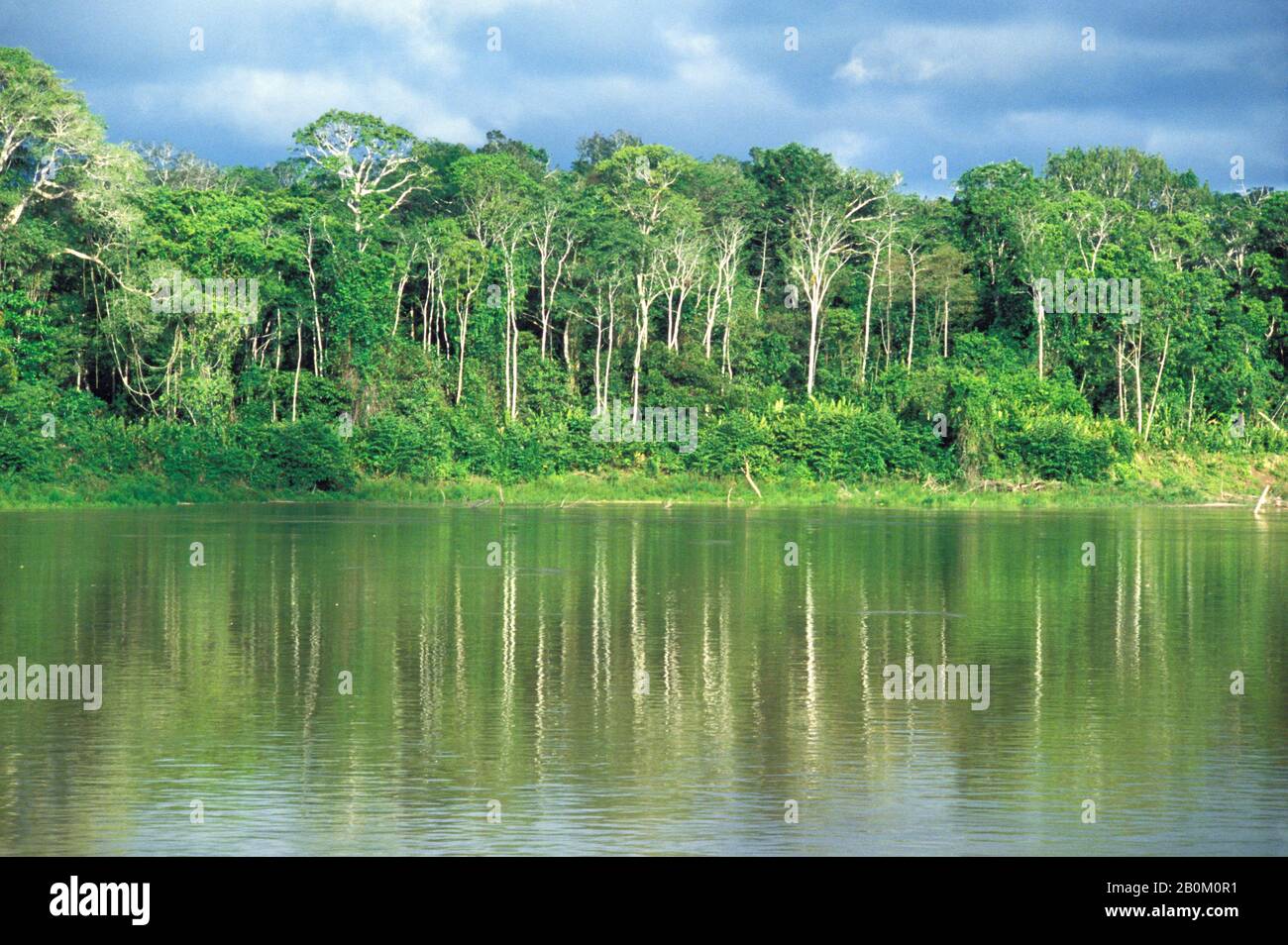

You’ve seen the photos. Those sweeping, emerald-green aerial shots that make the lungs of the earth look like a thick, uniform carpet. But if you actually stand at the base of a Kapok tree, looking up through the humidity, the scale of trees in the Amazon rain forest starts to feel a bit crushing. It’s not just "a lot of wood." It’s an architectural nightmare of competition.

Trees here don't just grow; they fight.

Actually, the Amazon is home to roughly 16,000 different tree species. That is a staggering number. To put it in perspective, if you walked through a temperate forest in North America or Europe, you might see ten or twenty species in a square mile. In the Amazon, scientists like Hans ter Steege have found hundreds of species packed into a single hectare. It’s chaotic.

The Giants Holding Up the Sky

The canopy isn't a flat roof. It’s a jagged, multi-layered mess. At the very top, you have the emergents. These are the "hyperdominants." While there are thousands of species, just about 227 species make up half of all the trees in the Amazon rain forest.

The Sumaúma, or Kapok (Ceiba pentandra), is the king of these. They can hit 200 feet. They have these massive, flared-out structures at the base called buttress roots. If you’ve ever wondered why they don't just tip over in the thin tropical soil, those roots are the answer. They act like organic kickstands.

Inside the wood, it's not all the same either. Some trees are dense enough to sink in water. Others, like the Balsa, are practically air. You also have the Brazil Nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa). These things are legally protected in Brazil, and for good reason. They can live for 500 to 1,000 years. Imagine a tree that was a sapling when the Black Death was sweeping Europe, still dropping 4-pound pods of nuts today.

Those pods are heavy. Seriously. If one hits you, it’s over.

🔗 Read more: UNESCO World Heritage Places: What Most People Get Wrong About These Landmarks

Why Soil is the Big Lie

Here is something most people get wrong: they think the soil in the Amazon is incredibly fertile because the forest is so lush.

It’s actually the opposite.

The soil is mostly "oxisols"—old, weathered, and remarkably nutrient-poor. The Amazon is essentially a closed-loop system sitting on a desert of dirt. When a leaf falls, it doesn't stay there. Fungi and bacteria break it down almost instantly. The trees in the Amazon rain forest have evolved to suck those nutrients back up before they can wash away in the daily downpours.

This is why deforestation is such a permanent disaster. When you cut the trees, you remove the entire nutrient bank. The soil that’s left behind is basically just orange clay that can’t support much for more than a few seasons.

The Walking Palm and Other Weirdness

Evolution gets weird when you’re desperate for light. Take the Socratea exorrhiza, or the Walking Palm. It has stilt roots that grow out of the trunk several feet above the ground.

Local guides love to tell tourists that these trees "walk" toward the sunlight. Scientists are a bit more skeptical. While the tree doesn't literally stroll across the forest floor, it can grow new roots in the direction of light and let the old ones on the shady side rot away, effectively shifting its position over years. It’s slow-motion survival.

💡 You might also like: Tipos de cangrejos de mar: Lo que nadie te cuenta sobre estos bichos

Then there’s the Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis). This tree literally changed the world’s economy. The "Rubber Boom" of the late 19th century built the Manaus Opera House in the middle of the jungle, but it also led to horrific exploitation of indigenous populations. The sap—latex—is the tree’s defense mechanism against bugs. We just figured out how to make tires out of it.

The Carbon Question

Everyone talks about "carbon sinks."

Basically, trees in the Amazon rain forest store about 150 to 200 billion tons of carbon. That’s a massive buffer against climate change. But it’s a fragile one. Research published in Nature recently suggested that parts of the Amazon are now emitting more CO2 than they absorb.

Why? Because of "dieback."

When the forest gets fragmented, the edges dry out. Trees that are used to a humid, moist interior start to die off. They rot. They release their stored carbon. It’s a feedback loop that’s hard to stop once it starts.

The Realities of Survival

If you're planning to actually see these trees, don't expect a pristine park. It's loud, it's buggy, and it's dark. Only about 2% of sunlight reaches the forest floor. That’s why every sapling is a coiled spring, waiting for a giant to fall so it can race toward the hole in the canopy.

📖 Related: The Rees Hotel Luxury Apartments & Lakeside Residences: Why This Spot Still Wins Queenstown

And the smells? It’s not just "flower" scents. It’s the smell of wet earth, rotting fruit, and sometimes, the pungent stench of the Stinkwood tree.

How to Actually Help (and what to avoid)

If you want to contribute to the preservation of these species, you have to look at the supply chain. Most "save the rain forest" campaigns are vague.

Instead, look for FSC-certified wood products. If you're buying mahogany or cedar that doesn't have a clear origin, there is a very high chance it was poached from indigenous lands.

Also, support the Amazon Sacred Headwaters Alliance. They focus on protecting the areas with the highest biodiversity—where the "mother trees" still stand.

Actionable Steps for the Conscious Traveler or Consumer

- Check your labels: If you buy Brazil nuts, you’re actually helping. These trees only produce fruit in undisturbed, primary forests because they need specific orchid bees for pollination. No forest, no bees, no nuts. Eating them gives the forest economic value.

- Use Satellite Tech: If you're a data nerd, check out Global Forest Watch. You can see near real-time alerts of where trees in the Amazon rain forest are being cleared.

- Diversify your donations: Smaller organizations like Rainforest Trust or Amazon Conservation Team often have lower overhead and work more directly with local communities than the massive "legacy" NGOs.

- Rethink Beef: It sounds cliché, but the vast majority of Amazon clearing is for cattle pasture. Reducing beef consumption, specifically from Brazilian exports, is the most direct way to lower the pressure on the forest frontier.

The Amazon isn't just a backdrop for a documentary. It's a high-stakes, biological machine. Every time a single massive Ceiba falls, the vibration is felt for miles, and the race for the light begins all over again. Understanding that struggle is the first step to actually respecting what’s left of it.