You’re at a party, or maybe you’re traveling in a region where the local spirits are distilled in a backyard shed rather than a regulated facility. You take a drink. It tastes a bit off—maybe a little "chemical"—but you shrug it off. Within 12 to 24 hours, the world starts looking like it’s covered in snow. Your head thumps. You feel like you've been hit by a truck. This isn't just a bad hangover. This is a medical emergency that can cost you your sight or your life.

Treatment for methanol poisoning isn't just about "getting the alcohol out." It is a high-stakes race against biology. Methanol itself—the simplest alcohol, often found in antifreeze, paint thinner, and bootleg liquor—isn't actually what kills you. It’s what your liver turns it into. Your body uses an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to break it down. Sounds helpful, right? Wrong. The process converts methanol into formaldehyde and then into formic acid. Formic acid is the real villain here. It attacks the optic nerve and causes metabolic acidosis, which basically means your blood becomes too acidic for your organs to function.

The First Line of Defense: Blocking the Enzyme

The core strategy for any effective treatment for methanol poisoning is simple: stop the conversion. If you can prevent the liver from turning methanol into formic acid, the body can eventually clear the methanol out through the lungs and kidneys without the toxic fallout.

Historically, doctors used ethanol—yes, regular drinking alcohol—to do this. It sounds crazy, but ADH has a much higher affinity for ethanol than methanol. If you saturate the system with ethanol, the enzyme stays busy with the "good" alcohol and ignores the "bad" one. But managing an IV drip of ethanol is a nightmare. Patients get drunk, they get rowdy, and their blood sugar can tank.

Nowadays, the gold standard is Fomepizole (Antizol). It’s a competitive inhibitor of ADH. It’s way easier to dose than ethanol and doesn't cause the central nervous system depression that makes ethanol so tricky to manage in a clinical setting. The problem? It’s incredibly expensive. Many hospitals in developing nations, where methanol outbreaks are most common due to "moonshine" or adulterated liquor, simply can't afford to keep it on the shelf. In those cases, doctors still reach for the whiskey or medical-grade ethanol. It’s a literal life-saver.

Correcting the Acidosis and Saving the Eyes

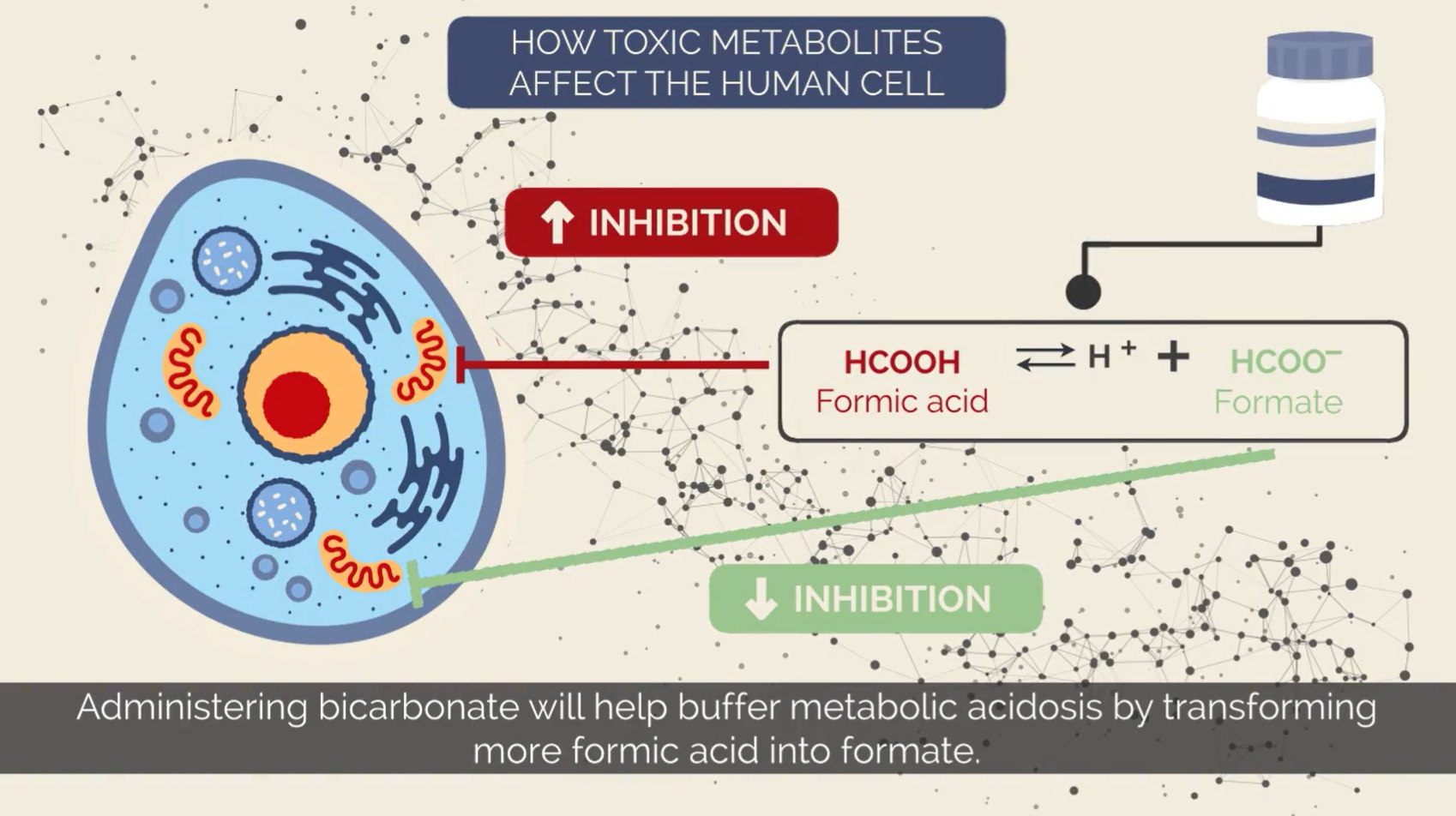

While blocking the enzyme is crucial, you also have to deal with the damage already done. Once formic acid starts building up, the blood’s pH drops. This is a crisis.

Doctors use sodium bicarbonate to neutralize the acid. It’s basically like giving a massive, medical-grade dose of Alka-Seltzer directly into the veins to bring the body’s chemistry back into balance. If the pH stays too low for too long, cells start dying. The brain and the eyes are the most sensitive.

Then there’s the "folate trick." This is a nuance often missed in basic medical summaries. Formic acid is normally broken down into carbon dioxide and water through a pathway that requires folate (vitamin B9). By giving the patient high doses of folic acid or leucovorin, clinicians can speed up the natural breakdown of the toxin. It’s not the primary cure, but it’s a vital supporting player in the recovery process.

When Dialysis Becomes Mandatory

Sometimes, the levels of methanol in the blood are just too high for medication alone. This is where hemodialysis enters the chat.

Hemodialysis is essentially an external kidney. It filters the blood through a machine to physically remove the methanol and the formic acid. If a patient is showing signs of vision loss, severe acidosis, or if their methanol concentration is above a certain threshold (usually 50 mg/dL), they need a machine. Fast.

- The machine pulls blood from the body.

- It passes the blood through a filter that catches small molecules like methanol.

- It balances the electrolytes and pH.

- The cleaned blood goes back into the patient.

It is highly effective, but it requires specialized equipment and staff. In rural areas or during mass poisoning events—like those seen in parts of Southeast Asia or Eastern Europe—the lack of dialysis machines is often why the mortality rate spikes so high.

The Symptoms You Can't Ignore

Kinda scary, right? The tricky part is the "latent period." You might feel fine for 6 to 30 hours after ingestion. This is because the liver takes time to produce enough formic acid to cause symptoms.

- The Snowstorm: Patients often describe their vision as if they are looking through a blizzard or at a "white-out." This is a classic sign of retinal damage.

- Abdominal Pain: Intense pain in the gut is common, often mistaken for simple food poisoning.

- Hyperventilation: The body tries to get rid of the acid by breathing faster, blowing off $CO_2$.

If you see someone who seems "drunk" but is breathing like they just ran a marathon and complaining they can't see the TV, that is a 911 situation. No exceptions.

Common Misconceptions About Methanol

People often think you can smell the difference. You can't. Methanol smells and looks almost exactly like ethanol. You also can't "burn it off" to check. The old myth that methanol burns with a green flame while ethanol burns blue is mostly a myth—impurities in the alcohol usually dictate the flame color more than the alcohol type itself.

Another big mistake is thinking that if you don't feel sick immediately, you're in the clear. The delay is the trap. By the time you feel the "snowstorm," permanent damage to the optic nerve may have already occurred. Early intervention is the only way to prevent lifelong blindness.

Real-World Logistics: The Oslo Outbreak Lessons

Dr. Knut Erik Hovda, a leading expert from the Oslo University Hospital, has spent years studying mass methanol poisonings. His work has shown that the biggest hurdle isn't the science of the treatment—it’s the logistics. In a mass casualty event, where 50 people show up at a small clinic, you don't have enough dialysis machines.

In these scenarios, the protocol shifts. You use whatever you have. If you have Fomepizole, you give it. If you only have vodka, you use it to keep the patients' ADH enzymes occupied until they can be transferred to a larger facility. It’s messy. It’s high-pressure. But it works.

💡 You might also like: How Much Melatonin Is Safe: The Truth About Those Tiny White Pills

Actionable Next Steps for Safety and Treatment

Methanol poisoning is rare in everyday life but common in specific travel or industrial contexts. Knowing what to do can save a life.

If you suspect someone has ingested methanol:

- Call Emergency Services Immediately: Do not wait for symptoms to appear. The window for blocking the enzyme is narrow.

- Do Not Induce Vomiting: It won't help once the alcohol is absorbed, and it risks aspiration.

- Identify the Source: If there is a bottle or container, bring it to the hospital. Doctors need to know if they are dealing with pure methanol, a mixture, or something else entirely like ethylene glycol (antifreeze).

- Monitor Breathing: If the person starts breathing rapidly, they are likely entering a state of severe acidosis. Keep them calm and upright.

For travelers and DIY enthusiasts:

- Avoid Unlabeled Spirits: If you're in a region known for bootleg alcohol, stick to bottled beer or commercially sealed products from reputable brands.

- Safety Gear: When working with industrial solvents or cleaners containing methanol, use a respirator and gloves. It can be absorbed through the skin or inhaled in high concentrations.

- Education: Ensure everyone in a workplace knows that "wood alcohol" is a deadly poison, not a substitute for cleaning alcohol.

Treatment for methanol poisoning is a miracle of modern toxicology, but it is entirely dependent on speed. The transition from a slight headache to permanent blindness can happen in the span of a single afternoon. If there is even a shred of doubt regarding a substance someone has consumed, seek medical help. Doctors would much rather treat a false alarm than a case of irreversible optic nerve death.