If you think transportation during the Industrial Revolution was just about a bunch of guys in top hats watching a steam engine chug along a track, you're missing the most chaotic part of the story. It wasn't a clean, linear progression. It was a mess. Imagine a world where moving a ton of coal ten miles cost more than the coal itself. That was the reality in the mid-1700s. People were desperate. They needed a way to move stuff without horses sinking knee-deep in mud every time it drizzled.

The sheer scale of the shift is hard to wrap your head around. Honestly, we talk about the "digital revolution" today like it's the biggest thing ever, but the jump from a packhorse to a locomotive was arguably more jarring. It changed how people perceived time itself. Before this, "fast" meant how long a horse could gallop before its heart gave out. Afterward? Speed was limited only by how much coal you could shove into a furnace.

The Canal Fever That Almost Broke Britain

Before the tracks, there was the water. You’ve probably heard of the Bridgewater Canal. It’s basically the "startup" that proved the concept. The Duke of Bridgewater had a coal mine in Worsley and a big problem: getting that coal to Manchester was expensive and slow. He hired James Brindley—a man who was supposedly illiterate but a total genius with water levels—to build a "bridge" for boats. When the Bridgewater Canal opened in 1761, the price of coal in Manchester literally dropped by half overnight.

Investors went nuts.

It was called "Canal Mania." Everyone with a spare shilling started throwing money at ditch-digging projects. Some were brilliant. Others were total scams or just poorly planned disasters that ended up as stagnant trenches. But the result was a massive, interconnected spiderweb of waterways across Britain. For the first time, you could move heavy, bulky goods like pottery from Josiah Wedgwood’s factories without half of it breaking on the bumpy dirt roads. These canals were the literal arteries of the early Industrial Revolution.

But they had a flaw. They were slow.

If a canal froze in winter, your supply chain died. If there was a drought in summer, the boats scraped the bottom. You were at the mercy of the weather, which is exactly what the new industrial class hated. They wanted control. They wanted a machine that didn't need to rest or drink water.

Why the Steam Engine Wasn't Just for Factories

We usually associate James Watt with factory chimneys, but the application of steam to transportation during the Industrial Revolution is where things got wild. It didn't start on tracks. It started with "road locomotives"—essentially terrifying, high-pressure steam carriages that would occasionally explode and scare the absolute life out of horses and pedestrians.

👉 See also: How to delete comments on Facebook: The stuff nobody tells you about cleaning up your timeline

Richard Trevithick is the name you should know here. He was a giant of a man, a Cornish wrestler, and a brilliant engineer who didn't get nearly enough credit because he was terrible at business. In 1801, he built the "Puffing Devil." It was a steam-powered carriage. He took it for a spin on Christmas Eve, drove it up a hill, and then—in a move that feels very human—parked it in a shed and went to a pub to celebrate. While he was drinking, the water boiled off, the engine overheated, and the whole thing burned to the ground.

That didn't stop him. By 1804, he put a steam engine on rails at the Penydarren Ironworks in Wales. It worked, but it was too heavy for the cast-iron rails of the time. They kept snapping. It took George Stephenson—the "Father of Railways"—to realize that you couldn't just build a better engine; you had to build a better system. The "Permanent Way."

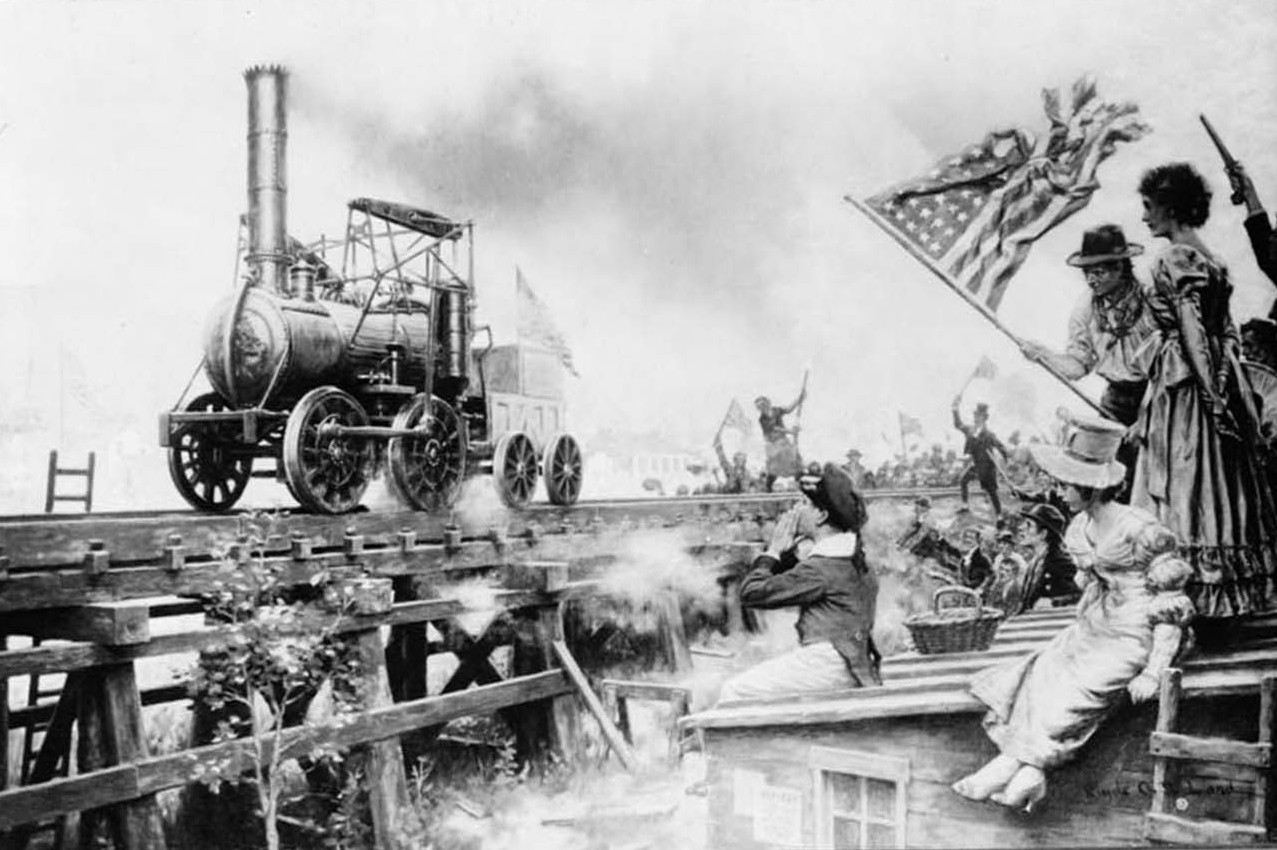

The Day the World Changed: 1830

If there’s one date that marks the birth of the modern world, it’s September 15, 1830. The opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. This wasn't just another mine-to-port line. It was the first "inter-city" railway. It carried people.

The Rocket, designed by Robert Stephenson (George’s son), won the Rainhill Trials by hitting the "blistering" speed of 29 mph. People were terrified. Some doctors actually claimed that the human frame couldn't withstand traveling at 30 miles per hour; they thought your brain might melt or you’d suffocate because the air would be pushed out of your lungs.

Obviously, that didn't happen.

Instead, what happened was the total annihilation of distance. Before the L&M Railway, a stagecoach trip between these two cities took about four hours on a good day. The train did it in under two. This created a weird psychological shift. Suddenly, people started thinking in minutes, not miles.

The Dark Side of the Tracks

Let’s be real for a second. It wasn't all progress and cheering crowds. Building these lines was brutal. The "navvies"—short for navigators—were the manual laborers who dug the tunnels and laid the ballast. They lived in squalid shanty towns, worked in incredibly dangerous conditions, and died by the thousands from accidents and cholera.

And then there was the social impact. If you were a small-town innkeeper on an old coaching road, the railway was the end of your world. Overnight, your business vanished as people bypassed your town at 30 mph. The "Railway Mania" of the 1840s was even bigger than the canal craze, and it led to a massive stock market crash. Fortunes were made, but many more were lost in the frenzy to lay tracks to nowhere.

🔗 Read more: Is Carbon Actually the Strongest Element on Earth? What the Science Really Says

Macadam and the Road Revolution

We can't just talk about trains. Transportation during the Industrial Revolution also saw the first major upgrade to roads since the Romans left. Before the 1800s, roads were basically just dirt paths. When it rained, they became quagmires.

Enter John Loudon McAdam.

He had a simple but revolutionary idea: drainage. He realized that if you built a road with a slight camber (a curve) and used layers of small, crushed stones, the weight of the traffic would actually pack the stones together into a solid, waterproof surface. This is where we get the term "macadam."

Telford and McAdam turned road-building into a science. This allowed the "Golden Age of Coaching." Mail coaches could suddenly maintain speeds of 10 mph, which sounds slow now, but was a total game-changer for communication. It meant a letter from London could reach Edinburgh in days rather than weeks. This was the internet of the early 19th century.

The Global Impact: Beyond Britain

While Britain was the laboratory, the sparks flew everywhere. In the United States, the Industrial Revolution and transportation were even more tightly linked because of the sheer size of the continent.

🔗 Read more: Why your phone number with 10 digits looks that way (and how it's actually changing)

- The Erie Canal (1825): This 363-mile "ditch" connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes. It made New York City the economic powerhouse it is today.

- The Steamboat: Robert Fulton’s Clermont proved that you could go against the current on the Hudson River. This changed everything for the Mississippi River trade, turning New Orleans into a massive hub.

- The Transcontinental Railroad: Eventually, the technology perfected in the rainy English countryside allowed the U.S. to stitch together two coasts, effectively ending the "frontier" era.

Nuance: It Wasn't All Steam

It’s easy to get hyper-focused on steam, but for most of the Industrial Revolution, the primary "engine" was still a horse. Even after the railways arrived, the number of horses in cities actually increased. Why? Because someone had to move the goods from the train station to the final shop or home.

The horse was the "last mile" delivery service of the 1800s. The streets of London and New York were packed with thousands of horses, which led to a different kind of crisis: manure. In 1894, The Times of London predicted that by 1950, every street would be buried under nine feet of horse dung. They didn't see the internal combustion engine coming, just like the canal owners didn't see the locomotive coming.

Actionable Insights: Learning from the Past

Looking back at the evolution of transportation during the Industrial Revolution offers some pretty blunt lessons for anyone interested in technology or business today.

- Infrastructure is Destiny: You can have the best invention in the world, but if the "rails" aren't there—whether that's physical tracks, 5G networks, or legal frameworks—it won't scale. Trevithick had the engine, but Stephenson built the system.

- The "S-Curve" of Adoption: New tech rarely replaces the old one instantly. There was a long period where canals, coaches, and trains all operated at once. If you're waiting for a "total" shift in any industry, you'll be waiting a long time.

- Disruption is Violent: The transition to rail destroyed the coaching industry and the canal business models. It didn't "innovate" them; it replaced them. Understanding whether a new technology is an "add-on" or a "replacement" is key to survival.

If you want to dive deeper into this, check out the work of Christian Wolmar—he’s arguably the best historian on how the railways specifically reshaped the modern world. Or, if you're ever in Manchester, visit the Science and Industry Museum. Standing next to a replica of The Rocket gives you a visceral sense of how small, noisy, and incredibly brave those early engineers really were.

They weren't just building machines. They were accidentally building the world we live in now. Every time you order something on Amazon and it shows up two days later, you're seeing the end result of a process that started with a bunch of guys digging a ditch in 1761.