You're sitting there, scrolling, maybe sipping coffee, and inside your skull, trillions of tiny sparks are flying. It’s chaotic. It’s silent. And honestly, it’s the only reason you can even feel the weight of the phone in your hand. This whole process, transmission at a synapse, is basically the postal service of the nervous system, but way faster and with a lot more drama. If one tiny chemical messenger gets lost or shows up too late, everything from your mood to your ability to wiggle your toes starts to glitch.

Think of your brain as a dense forest of 86 billion trees. These trees—neurons—don't actually touch. There’s a microscopic gap between them called the synaptic cleft. It’s an incredibly small space, about 20 to 40 nanometers wide. For perspective, a human hair is roughly 80,000 nanometers thick. So, how does a signal jump that gap? It can’t just leap. It has to change form. It’s like a runner reaching a river and having to hop into a boat to get to the other side before jumping back out to keep running.

🔗 Read more: Calories 1 cup cherries: What the Labels Often Miss

The Moment of Impact: How the Spark Happens

Everything starts with an electrical impulse called an action potential. This is a "do or die" moment. The neuron doesn't do "maybe." It either fires at full strength or it doesn't fire at all. When that electrical wave hits the end of the line—the axon terminal—it triggers a massive change in the neighborhood.

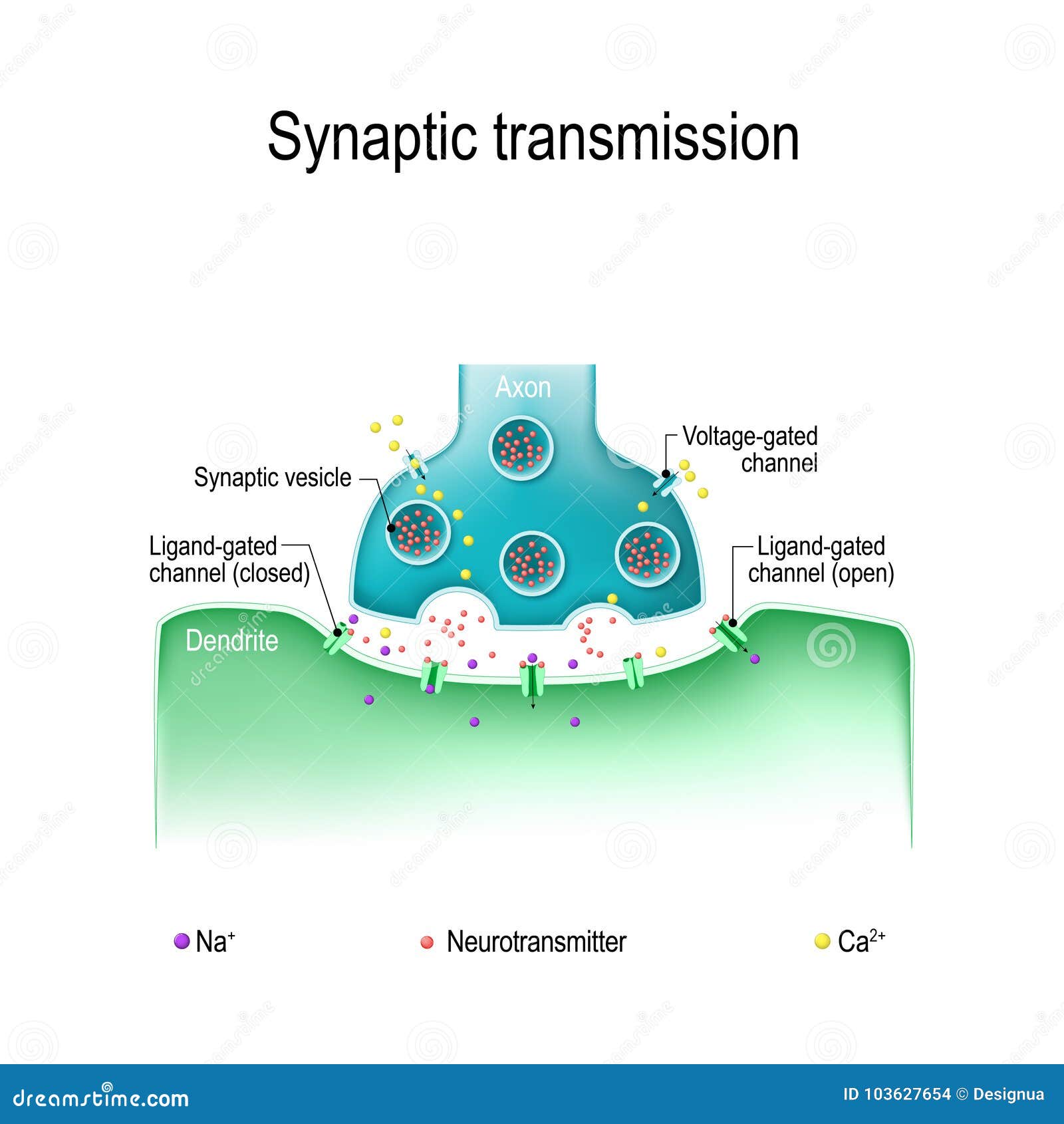

Suddenly, voltage-gated calcium channels fly open. Calcium ions ($Ca^{2+}$) rush into the cell like fans at a sold-out concert. This influx is the signal for the neurotransmitters, which are hanging out in little storage bubbles called vesicles, to move toward the edge. They fuse with the membrane and dump their contents into the gap. This process is called exocytosis. It’s messy, fast, and incredibly precise.

Once those chemicals—think dopamine, serotonin, or glutamate—are in the gap, they float across to the next neuron. They’re looking for a specific lock to fit their key. These are the receptors on the postsynaptic membrane. When they click into place, they open new doors, allowing ions to flow into the next neuron, and the electrical signal starts all over again.

The Mystery of Why Some Signals Just Stop

Not every signal makes it. And that’s a good thing. If every single "fire" command reached its destination, you’d be a shaking, overstimulated mess. This is where the nuance of transmission at a synapse gets interesting.

👉 See also: Home Remedy for Hangover: What Actually Works When Your Head Is Screaming

You have excitatory signals and inhibitory signals.

Glutamate is the big "go" signal. It’s the gas pedal. On the flip side, you have GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), which is the "whoa there" signal. When GABA binds to a receptor, it usually lets in negatively charged chloride ions. This makes the inside of the neuron even more negative, making it harder for an action potential to fire. It’s a literal biological brake system.

Researchers like those at the Max Planck Institute have spent decades trying to map how these balances shift. If you have too much excitation and not enough inhibition, you might see something like a seizure. If it’s the other way around, you get sedation or even coma. Your entire personality, your anxiety levels, and your sleep cycles are just the result of these two forces constantly tugging at each other in the dark.

The Cleanup Crew You Never Think About

What happens to the chemicals left floating in the gap? If they stayed there, the receiving neuron would just keep firing forever. That’s bad. Real bad.

The body has two main ways to fix this. First, there’s "reuptake." The sending neuron basically acts like a vacuum cleaner, sucking the neurotransmitters back up to be recycled and used later. This is exactly what SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) mess with. By slowing down the vacuum, they keep more serotonin in the gap for longer, which helps people struggling with depression.

👉 See also: Standing Dumbbell Flys Chest Secrets: Why Your Form is Probably Killing Your Gains

The second way is enzymatic degradation. Specific enzymes roam the synapse like a cleanup crew, shredding neurotransmitters into pieces so they can't bind to receptors anymore. Acetylcholinesterase does this to acetylcholine, which is the chemical that tells your muscles to contract. If that enzyme didn't work, your muscles would lock up and never relax. Certain nerve gases actually work by blocking this cleanup crew, showing just how vital the "off" switch is to your survival.

Why Synapses Are the Real Stars of Learning

Most people think learning happens by growing new brain cells. It doesn’t. Well, rarely. Learning is actually about changing the strength of the transmission at a synapse. This is called synaptic plasticity.

Donald Hebb, a pioneer in neuropsychology, famously suggested that "neurons that fire together, wire together." When you practice a guitar chord or a new language, you are repeatedly forcing signals across specific synapses. Over time, those synapses get "stronger." They might grow more receptors, or the sending neuron might start releasing more neurotransmitters. This is Long-Term Potentiation (LTP).

It’s why the first time you try to do a squat, you feel wobbly. Your brain is trying to find the right path. By the hundredth time, the synapse is so efficient that the signal glides through. You don’t even have to think about it. The path has been paved.

When Things Go Sideways

When we talk about brain disorders, we're usually talking about a failure in synaptic transmission. It’s rarely the whole brain that’s "broken"—it’s the communication.

- Alzheimer’s: In the early stages, it’s not just that neurons are dying; it’s that the synapses are being pruned away or blocked by amyloid-beta plaques. The "chat room" is getting disconnected.

- Parkinson’s: This is a specific failure in the synapses that use dopamine in the substantia nigra. Without enough dopamine crossing those gaps, the "start moving" signal never quite gets loud enough to work.

- Addiction: Drugs hijack the reward synapse. They flood the gap with dopamine or prevent reuptake, making the "that felt great" signal hit a thousand times harder than it should. The brain reacts by removing receptors to protect itself, which is why addicts eventually need more of the drug just to feel "normal."

Small Gaps, Massive Consequences

It is wild to think that everything you are—your first memory of rain, your fear of spiders, your ability to solve a math problem—exists in these tiny gaps. We aren't just a collection of cells; we are the electrical and chemical "noise" happening between them.

The complexity is staggering. A single neuron can have thousands of synapses connecting to it. It’s constantly weighing all the "go" and "stop" signals it receives, performing a sort of biological calculus every millisecond to decide whether to pass the message along.

If you want to keep your synapses firing well, the science is actually pretty straightforward, even if it sounds like cliché advice. Sleep is the big one. During sleep, your brain literally flushes out metabolic waste that can gunk up the synaptic cleft. Exercise increases Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which is like fertilizer for your synapses, helping them stay "plastic" and ready to learn.

Moving Forward With This Knowledge

Understanding how your brain communicates isn't just for biology exams. It changes how you look at your own habits. If you're trying to learn a skill, don't just "do it." Do it with the intent of strengthening a physical connection in your head.

To optimize your own synaptic health:

- Prioritize deep sleep to allow for "synaptic scaling," where your brain resets the strength of connections so they don't get overloaded.

- Challenge your brain with novel tasks to trigger the formation of new dendritic spines, giving signals more places to land.

- Watch your magnesium levels. Magnesium sits inside certain receptors (like the NMDA receptor) and acts as a gatekeeper, preventing the "fire" signal from being triggered by random background noise. Without enough of it, your synapses can become hyper-excitable, leading to "brain fog" or anxiety.

Focus on the architecture of the signal. Every time you learn something, you are physically remapping your inner world, one tiny chemical splash at a time.