You’re staring at a lab report or a chemistry quiz. The number is 500. Is it one significant figure? Is it three? Suddenly, your brain feels like it’s short-circuiting because your teacher said one thing, but the textbook says "it depends." Honestly, trailing zeros significant figures are the bane of every science student's existence. It’s the one part of precision measurement that feels more like a grammar rule than actual math.

But here’s the thing. Precision isn’t just about being "right." It’s about not lying to whoever reads your data. When you write down a number, you're making a claim about how well you actually measured that thing. If you say a gold bar weighs 400 grams, but your scale is a cheap kitchen model from the 90s, claiming 400.00 grams is basically scientific fraud.

Why Trailing Zeros Drive Everyone Crazy

Most people get leading zeros. They’re just placeholders. $0.005$ has one sig fig. Easy. Most people get "sandwich" zeros. $505$ has three. Also easy. But trailing zeros? They’re the chameleons of the math world.

The fundamental rule you've probably heard is that trailing zeros are only significant if there is a decimal point. So, in the number 120.0, all four digits matter. In 120, maybe only two do. It’s a distinction that seems small until you’re calculating the structural integrity of a bridge or the dosage of a high-potency medication.

Think about a standard ruler. If it only has marks for every centimeter, and an object lands exactly on the 10 mark, you can't honestly say it's 10.00 cm. You didn't measure the millimeters. You only know it's roughly 10. That's why trailing zeros significant figures matter—they communicate the "honesty" of your measurement tool.

The Decimal Point Power Move

If there is a decimal point anywhere in the number, those trailing zeros are suddenly "on the clock." They are working. They represent a deliberate choice by the person who recorded the data to say, "I checked this specific decimal place, and it was a zero."

Take the number 45.00. This has four significant figures. Those two zeros at the end aren't there for decoration. They tell us that the measurement was precise to the hundredths place. If the person had just written 45, they’d be saying they only checked the whole numbers. It’s a huge difference in the world of engineering. If you’re machining a part for a SpaceX Raptor engine, 45mm and 45.00mm are worlds apart. One might fit; the other might cause a catastrophic failure.

Ambiguity: The 500 Problem

What happens when you write 500? No decimal. No overbar. Just 500.

🔗 Read more: Hubble telescope real pictures: What the public often gets wrong about those colors

This is where it gets messy. In a strictly academic sense, 500 has only one significant figure: the 5. The zeros are just there to tell you the magnitude. They’re placeholders. They’re saying "this is in the hundreds," but we aren't sure about the tens or the ones.

But wait. What if you actually measured exactly 500?

Some scientists use a "check" or a bar over the last significant zero to show it counts. Others just put a decimal at the very end like this: 500. That little dot turns those two lazy zeros into high-functioning significant figures. It’s a shorthand that saves lives—or at least saves grades.

Real-World Stakes: Science Isn't Just Paperwork

Let's look at the work of someone like Dr. John Taylor, who wrote An Introduction to Error Analysis. He spent an entire career explaining that measurements are never "perfect." They are always an interval.

When we talk about trailing zeros significant figures, we are defining that interval.

If a chemist at a company like Pfizer is measuring an active ingredient and writes "100 mg," they are implying an uncertainty. If the rule says trailing zeros without a decimal aren't significant, that "100" could technically mean anything from 50 to 149 depending on how you round. That's a massive range for a drug. This is why you will almost always see 100.0 mg or scientific notation in professional settings.

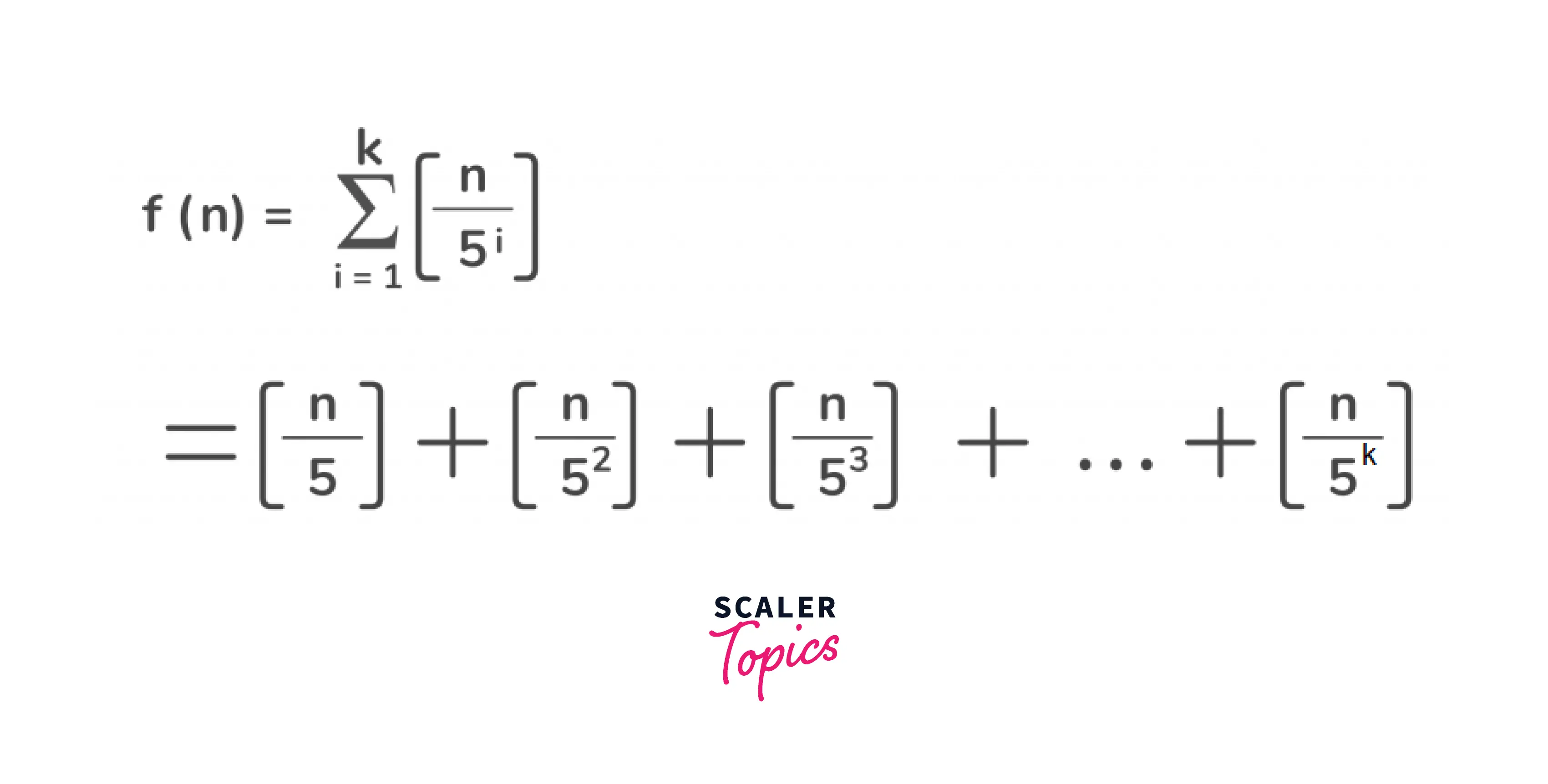

Scientific notation is the "clean" way out of this mess. Instead of arguing over 5,000, you write $5.0 \times 10^3$ for two sig figs or $5.000 \times 10^3$ for four. It’s unambiguous. It’s precise. It’s also a bit of a pain to write out every time, which is why we still struggle with the shorthand.

The Rules (Varying as They Are)

Let's break down how this actually looks in practice. No fancy tables, just the raw logic.

📖 Related: Apple Arden Fair Sacramento CA: What Most People Get Wrong

If you have a number like 0.00450, you have three significant figures. The first three zeros are "leading"—they don't count toward precision. The 4 and 5 obviously count. That last zero? It’s a trailing zero after a decimal. It counts. It shows the measurement went one step beyond the 5.

Now, look at 450,000. Unless there’s a decimal point at the end, this has only two significant figures. The zeros are just filling space so we know the number isn't 45. It feels weird to ignore four digits, but in the eyes of a physicist, those digits are "unreliable" data points.

Sorta makes sense, right? If you hear someone say a stadium holds 50,000 people, you don't assume there are exactly 50,000.0 individuals. You assume it’s a rounded estimate. That’s the "intuition" behind the sig fig rules.

Common Pitfalls and Why They Happen

A lot of students get tripped up by "exact numbers."

If you have 12 eggs in a dozen, how many sig figs is that? It’s infinite. You can't have 12.1 eggs. Trailing zeros significant figures don't apply to counted items or defined constants. If you’re converting meters to centimeters and use the number 100, that 100 is "perfect." It doesn't limit the precision of your final answer.

The real trouble starts in multi-step calculations. If you’re multiplying $2.50$ (three sig figs) by $40$ (one sig fig), your answer can only have one significant figure.

$2.50 \times 40 = 100$

Mathematically, it's 100. But in terms of sig figs, you’d have to write it as 100 (which conveniently has one sig fig). If the 40 had been 40.0, your answer would be 100. (with a decimal) or $1.00 \times 10^2$. This is where people lose points on exams and where engineers occasionally make expensive mistakes.

🔗 Read more: Galaxy Note 3: Why This Weirdly Leather-Stitched Phone Still Matters

Accuracy vs. Precision: The Secret Context

We use these terms interchangeably in casual talk, but they’re different.

Accuracy is how close you are to the "true" value.

Precision is how consistent your measurements are—and sig figs are the language of precision.

Trailing zeros are the indicators of that precision. When you see $1.0000$ grams, you are looking at a measurement made with a very expensive, very sensitive analytical balance. When you see $1$ gram, you’re looking at something weighed on a scale that might as well be a seesaw.

The NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) has incredibly strict guidelines on this. They don't just "guess" about trailing zeros. They use specific uncertainty budgets. For the rest of us, sticking to the standard sig fig rules is the best way to ensure our data isn't misleading.

Getting It Right Every Time

If you're ever in doubt, convert the number to scientific notation. It’s the ultimate "BS detector" for trailing zeros.

- Identify if there is a visible decimal point.

- If yes, every zero at the end is significant.

- If no, the trailing zeros are just placeholders.

- Check if the number is an "exact count" (like 5 people) or a definition (1km = 1000m). If it is, ignore sig fig rules for that number.

- When in doubt, use scientific notation to be crystal clear.

Instead of writing 1200, write $1.2 \times 10^3$. If those zeros actually matter, write $1.200 \times 10^3$. It removes the guesswork and makes you look like you actually know what you're doing in the lab.

Actionable Steps for Better Data

Start by auditing your own measurement tools. If you're using a digital scale that reads to two decimal places, your data should always reflect that, even if the numbers are zeros. Writing "5g" when your scale says "5.00g" is actually throwing away valuable information.

Next, when performing calculations, always wait until the very last step to round. If you round your trailing zeros too early, you'll introduce "rounding error," which compounds. Keep all your digits in the calculator, then apply the trailing zeros significant figures rules at the end to determine where to cut the number off.

Finally, adopt the habit of using the decimal point for clarity. If you mean exactly one hundred, write "100." with the decimal. It’s a small mark that changes the entire meaning of your data. It moves you from "guessing" to "measuring," and that's a shift that defines professional work in any technical field.