You’ve probably seen them in history textbooks or during a late-night scroll through a historical "oddities" forum. Grainy, black-and-white images showing lines of indigenous people wrapped in blankets, trudging through the snow. Maybe there’s a caption that makes your heart sink, claiming these are trail of tears photos captured during the forced removal of the Cherokee or Choctaw. It feels real. It looks real.

Except it isn't. Not really.

The timing is just wrong. History is messy like that. The primary removals of the "Five Civilized Tribes"—the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw—took place roughly between 1830 and 1850. Louis Daguerre didn't even introduce his daguerreotype process to the world until 1839. Photography was in its absolute infancy, a novelty for the wealthy in Parisian studios or New York galleries, not a portable tool for documenting human rights abuses in the American wilderness.

The ghost in the lens: Why there are no trail of tears photos

Think about the gear. Early photography wasn't just "pointing and clicking." It involved massive wooden boxes, fragile glass plates, and volatile chemicals that had to be mixed on the spot. It was physically impossible to lug that equipment alongside the forced marches through the swamps of the South or the frozen terrain of Illinois and Missouri.

There are zero—literally zero—authenticated photographs of the 1838 Cherokee removal.

When people search for trail of tears photos, they usually find images from the 1890s or early 1900s. These are often photos of the Navajo "Long Walk" or much later resettlements in Oklahoma. Sometimes, they are staged reenactments from the early days of cinema. We want to see the evidence. We crave that visual connection to the tragedy. But the lack of photos is actually a testament to how early this horror occurred in the timeline of American expansion.

The famous "Trail of Tears" painting that everyone thinks is a photo

If you close your eyes and picture the removal, you’re likely seeing Robert Lindneux’s work. He painted "The Trail of Tears" in 1942. Yes, 1942. That’s over a hundred years after the event. Lindneux was a prolific painter of the American West, and while his work is emotionally resonant and based on historical accounts, it's a mid-20th-century interpretation.

It’s iconic. It’s on the cover of half the books on the subject.

📖 Related: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

But it’s a painting.

We often mistake well-rendered historical art for "visual proof," but every brushstroke in that image was a choice made by an artist who wasn't there. He wasn't standing in the cold. He was in a studio, trying to piece together a narrative for a public that had largely forgotten the specifics of the 1830s.

If the photos aren't real, what are we actually looking at?

Search results for trail of tears photos often serve up the work of Edward S. Curtis. Curtis is a controversial figure in the world of ethnography. Between 1900 and 1930, he took thousands of photos of Native Americans. His goal was to document a "vanishing race," a concept that is deeply problematic and arguably racist in its premise.

Curtis often carried a "costume trunk."

He would ask his subjects to remove their modern clothes—the denim and cotton shirts they actually wore in 1905—and put on traditional buckskins or headdresses that they hadn't worn in generations. He wanted to capture an "authentic" past that didn't exist anymore. When you see a high-contrast, beautiful portrait of a Cherokee elder and it’s labeled as a "removal photo," you’re looking at a Curtis-style romanticized recreation, not a documentary snapshot of 1838.

Then there are the photos of the "Land Run" in Oklahoma.

By the late 1880s and 1890s, cameras were everywhere. You’ll see photos of indigenous people being moved again or standing outside of government allotment offices. These are tragic, and they represent the continuation of the same policy, but they aren't the Trail of Tears. Confusing the two eras actually does a disservice to the survivors. It collapses a century of distinct struggles into one single, blurry moment.

👉 See also: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

The geography of memory: Landscapes as "photos"

Since we can't look at the people through a lens, historians and descendants have turned to the land. This is "landscape as witness."

The Mantle Rock site

In Smithland, Kentucky, there is a massive sandstone arch known as Mantle Rock. During the winter of 1838–1839, thousands of Cherokee were stranded there because the Ohio River was frozen solid, preventing the ferry from crossing. They camped in the bitter cold. People died there every single day.

If you take a photo of Mantle Rock today, you aren't seeing people in blankets. You’re seeing the silence they left behind. To many, these "place-based" trail of tears photos are more haunting than any staged reenactment. The moss on the rocks and the stillness of the woods carry the weight of the 4,000 lives lost during the Cherokee removal alone.

The "Water Route" vs. the "Land Route"

Most people forget there was a water route. The government used steamboats and flatboats to move thousands of people down the Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, and Arkansas rivers. These trips were often faster but equally deadly due to cholera outbreaks and scalding boiler explosions.

We have photos of the riverbanks today. We have sketches made by travelers who passed these boats. But the actual faces of those on the decks? They are lost to time.

The danger of "Historical Mislabeling"

Why does it matter if a photo is labeled correctly? Basically, because truth is the only thing we owe the victims of the removal.

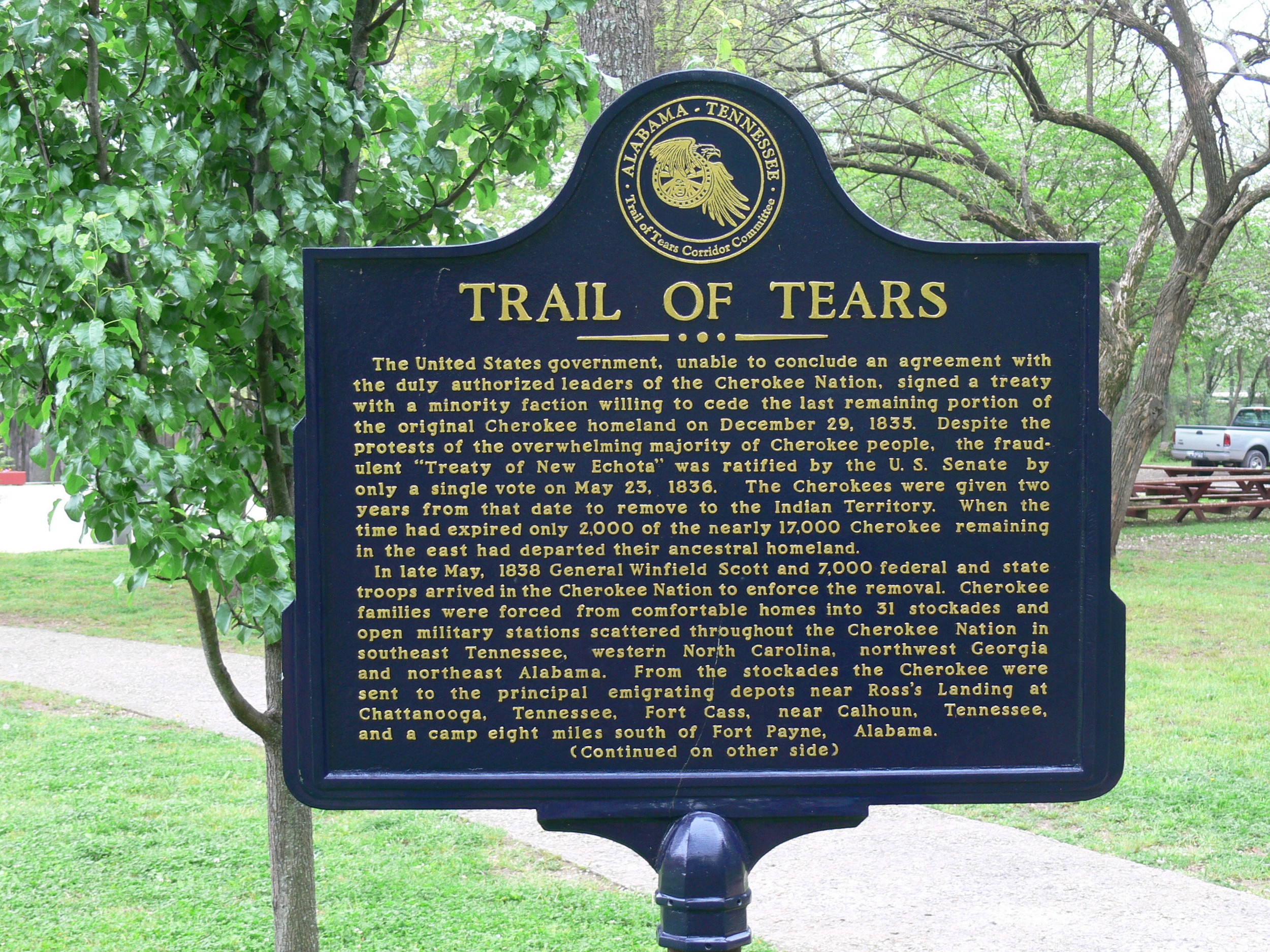

When we circulate a photo from 1910 and call it the Trail of Tears, we are participating in a sort of historical erasure. We are saying that all native suffering looks the same. We are ignoring the specific political climate of the Jacksonian era—a time of intense legal battles, Supreme Court cases (like Worcester v. Georgia), and a very specific type of betrayal by the American government.

✨ Don't miss: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

The Cherokee were a literate nation. They had the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper. They were lawyers, farmers, and printers. A photo from 1838—if it existed—would show people wearing a mix of traditional moccasins and European-style coats, carrying Bibles and legal papers. It wouldn't look like the "wild" imagery we see in late 19th-century westerns.

Real visual artifacts you can actually find

While trail of tears photos don't exist, other visual records do. These are arguably more powerful because they are contemporary to the event.

- The Missionary Journals: Samuel Worcester and others kept meticulous records. Some included small sketches of the camps.

- The Benjamin Reinhardt Portraits: While not of the trail itself, portraits of leaders like John Ross or Major Ridge give us the "who." We can look into the eyes of the men who signed the Treaty of New Echota and those who fought it.

- Physical Objects: The "Trail of Tears" is documented in the quilts carried by women, the small handheld items that survived the 1,000-mile journey, and the handwritten rosters maintained by the conductors of the detachments.

Modern documentary photography

Today, photographers like Tiana Williams-Claussen or those working with the National Trail of Tears Association document the "Commemorative Walks." These are photos of modern descendants retracing the steps of their ancestors.

These are real photos. They are vivid. They show the resilience of the nations that were supposed to have "vanished." Seeing a young Cherokee woman in 2024 walking through a forest in Missouri is a more accurate "photo of the Trail of Tears" in a spiritual sense than a mislabeled 1900s archival shot.

How to spot a fake or mislabeled image

If you're researching for a project or just curious, keep these red flags in mind when you see something claimed as an original Trail of Tears photo:

- The "Film Look": If the image has a cinematic quality or looks like a still from a movie, it probably is. Many people use screengrabs from the 1990s documentary The Trail of Tears: Cherokee Legacy and pass them off as historical.

- Clothing Discrepancies: In the 1830s, Southeast tribes had a very specific style—turban-style headwraps for men and long calico dresses for women. If the people in the photo are wearing Plains-style eagle feather warbonnets, it’s a 100% guarantee it’s not the Trail of Tears.

- The Camera Tech: If the photo is crisp, has a wide depth of field, or shows "action" (people moving quickly without blurring), it’s definitely from a much later era. Early daguerreotypes required subjects to sit perfectly still for long periods.

Moving beyond the search for a snapshot

The obsession with finding trail of tears photos is understandable. We live in a visual age. If we can't see it, we struggle to feel its full weight. But the power of this history lies in the oral traditions and the written records that survived when the people almost didn't.

Instead of looking for a photo that doesn't exist, look at the maps. Look at the primary source documents from the National Archives. Read the letters written by soldiers who were horrified by what they were ordered to do. One soldier, John G. Burnett, later wrote about how he saw "the helpless Cherokee" driven like cattle. His words provide a clearer "picture" than any grainy, mislabeled photograph ever could.

To truly understand the visual history of the removal, start by visiting the actual sites. The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail spans nine states. Standing on the banks of the Mississippi at Trail of Tears State Park in Missouri provides a perspective that a Google Image search never will. You can see the geography that claimed so many lives and realize that the lack of photos doesn't make the history any less present.

Next Steps for Research:

- Verify the Source: Use the National Park Service (NPS) Trail of Tears gallery for authenticated historical sketches and maps.

- Check the Date: If an image is dated before 1840, it's almost certainly a painting or a later lithograph, not a photo.

- Consult Tribal Resources: Visit the official websites of the Cherokee Nation, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, or the Choctaw Nation. They curate their own histories and provide context that external "history" blogs often miss.

- Visit the Museums: The Museum of the Cherokee Indian in North Carolina and the Cherokee National Museum in Oklahoma house the most accurate visual representations of the era.