You’ve probably seen the paintings. Those haunting images of people wrapped in blankets, trudging through snow, looking utterly defeated. It’s the standard visual for the Trail of Tears. But there is a massive part of the story that gets skipped in most history books. What happened when they actually stepped foot in what we now call Oklahoma?

It wasn’t just an ending. Honestly, for the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw, it was a brutal, chaotic new beginning in a place that looked nothing like the lush, mountainous homes they were forced to leave behind in the Southeast.

The Trail of Tears Oklahoma wasn't a single path. It was a messy, state-sponsored catastrophe. People arrived at different times, in different conditions, and with very different ideas about how to survive. Some were "voluntary" emigrants who left early to secure better land, while others were prodded at bayonet point into what was then called Indian Territory.

The Arrival No One Prepared For

Imagine walking 1,000 miles. Your shoes are gone. You’ve buried your grandmother by the side of a road you didn't want to be on. Then, you cross a line into a dusty, unfamiliar prairie, and a government agent basically says, "Okay, you're here. Good luck."

That was the reality.

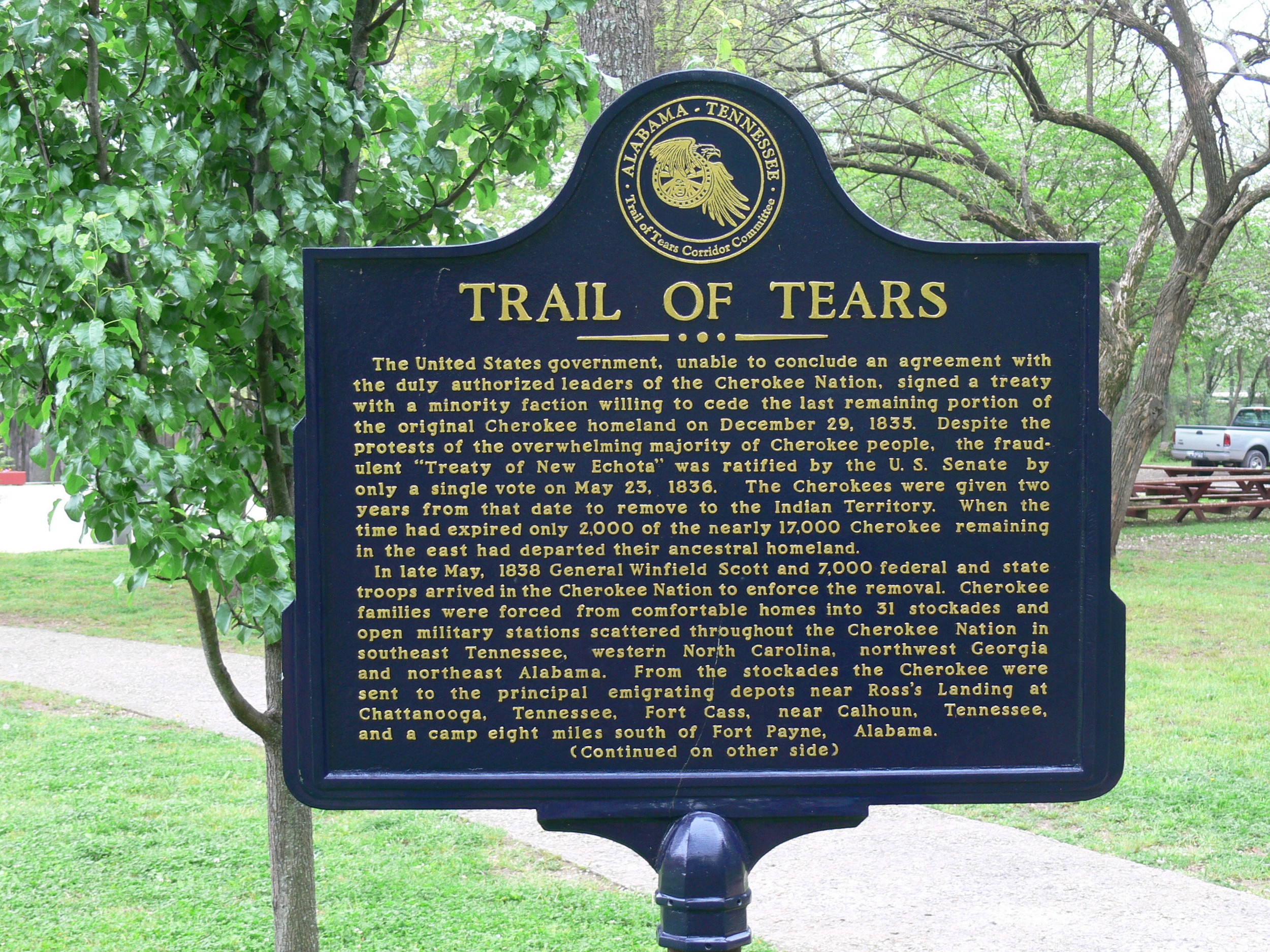

When the main detachments of the Cherokee arrived in 1839, they didn't find a land of milk and honey. They found a political powder charge. The "Old Settlers"—Cherokees who had moved west years earlier—already had a government and a way of life in place. Suddenly, thousands of traumatized, starving newcomers showed up, led by Chief John Ross. Tensions didn't just simmer; they boiled over. Within months, several leaders who had signed the Treaty of New Echota—the document that legally (if fraudulently) authorized the removal—were assassinated. Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot were killed on the same day in coordinated strikes.

The Trail of Tears Oklahoma era was defined by this internal civil war as much as it was by the struggle against the elements.

Not just a walk in the woods

We often focus on the walking. But the water routes were arguably worse. Steamboats like the Monmouth were death traps. In 1837, the Monmouth collided with another ship on the Mississippi River while carrying over 600 Creek Indians. Over 300 of them drowned. If you survived the river, you still had to face the "fever" of the lowlands once you hit the Arkansas border.

The geography of Oklahoma itself was a shock. The eastern part of the state, where the tribes were settled, has the Ozark plateau and the Ouachita Mountains, but it was a far cry from the deep woods of Georgia or the Everglades of Florida.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Rebuilding from the Dirt Up

How do you build a nation when you have nothing? You start with the law.

Despite the trauma, the Five Tribes (often called "Civilized" by white settlers of the time, though they had their own complex social structures long before contact) were incredibly resilient. They built Tahlequah. They built Tuskahoma. They established the Cherokee Female Seminary in 1851—the first higher education institution for women west of the Mississippi.

It’s kinda wild to think about.

In less than twenty years after the last survivor limped into the territory, they had newspapers like the Cherokee Advocate printing in both English and the Sequoyah syllabary. They weren't just "surviving." They were asserting sovereignty in a way that terrified the surrounding states.

But it wasn't equal. We have to be honest here. The tribes brought their own complexities with them, including enslaved African Americans. The "Trail of Tears" wasn't just a Native American journey; it included hundreds of Black people who were forced West alongside their masters. This created a unique, often painful legacy in Oklahoma that people are still unpacking today regarding the "Freedmen" and tribal citizenship.

The Geography of Loss

If you drive through eastern Oklahoma today, you’ll see the markers. Park Hill. Fort Gibson. These aren't just dots on a map; they were the arrival hubs.

- Tahlequah: Became the capital of the Cherokee Nation.

- Okmulgee: The heartbeat of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

- Tishomingo: The seat of the Chickasaw.

The land was divided up, but it wasn't yours to keep forever. That’s the kicker. The US government promised this land would be theirs "as long as grass grows and water runs."

Spoiler: It wasn't.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

By the late 1800s, the Dawes Act moved in to break up communal tribal lands into individual allotments. The goal? To weaken tribal governments and open up "surplus" land for white settlers. This led to the Land Runs, which basically erased the borders of the "Indian Territory" the tribes had died to reach.

Why the "Trail of Tears Oklahoma" Story Still Rattles Us

Most people think of history as something that happened to people who are long gone. In Oklahoma, the Trail is yesterday. You talk to a Cherokee citizen today, and they can tell you exactly which detachment their family was in. They might tell you about the "White Path" or the "Northern Route."

It’s personal.

There’s also the legal side. You might remember the McGirt v. Oklahoma Supreme Court case from 2020. That case basically hinged on the fact that the reservations established after the Trail of Tears were never technically disestablished by Congress. It turned the legal world upside down because it acknowledged that, legally speaking, a huge chunk of eastern Oklahoma is still Indian Country.

That doesn't happen if the history is dead. It only happens because the treaties signed during the removal era still carry the weight of federal law.

Common Misconceptions to Toss Out

- It was only the Cherokee. Nope. While the Cherokee experience is the most documented, the Choctaw were actually the first to be moved under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. They lost thousands to cholera and exposure.

- They were all poor. Many members of the tribes were wealthy planters and businessmen. They lost mansions, ferries, and businesses. The removal was a massive redistribution of wealth from Native hands to white speculators.

- Oklahoma was empty. It definitely wasn't. The Osage and Quapaw already lived there. Forcing the Southeastern tribes into Oklahoma created decades of conflict between "immigrant" tribes and "indigenous" Plains tribes.

Practical Ways to Trace the History

If you actually want to understand the Trail of Tears Oklahoma, you can't just read a Wikipedia page. You have to see the physical reality of the arrival.

First, head to the Cherokee National Capitol in Tahlequah. It’s not a museum piece; it’s a living part of a city. You can feel the weight of the reconstruction there.

Next, check out the Hunter’s Home (formerly the George M. Murrell Home) in Park Hill. It’s the only surviving antebellum plantation mansion in Oklahoma owned by a Cherokee family. It gives you a stark look at the lifestyle some attempted to transplant from the South.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Finally, visit the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail markers that dot the eastern highways. Standing at a river crossing in the middle of a humidity-soaked July gives you a tiny, tiny fraction of the perspective on what it was like to arrive here with nothing but the clothes on your back.

The Real Actionable Takeaway

History isn't a straight line. The story of the Trail of Tears Oklahoma is a cycle of removal, survival, and legal battles that continue in 2026.

To truly respect this history, move beyond the "victim" narrative. Look at the constitutions the tribes wrote. Look at the languages they preserved despite boarding schools designed to kill them.

Support authentic tribal tourism. Instead of buying a "native-style" trinket at a gas station, go to the Cherokee National Heritage Center. Buy art from actual citizens of the Five Tribes. Read the Cherokee Phoenix, which is still being published today.

The best way to honor those who died on the Trail is to acknowledge the sovereignty of those who survived it. They didn't just come to Oklahoma to disappear; they came to stay, and they are still there, running businesses, practicing law, and keeping their culture alive against odds that would have broken most nations.

Key Steps for Further Research:

- Research the inter-tribal conflicts that occurred immediately following arrival in the 1830s to understand the complexity of the "Old Settler" vs. "Newcomer" dynamics.

- Study the 1866 Treaties, which fundamentally changed tribal borders and rights after the Civil War.

- Map the Northern Route vs. the Water Route to see exactly which Oklahoma counties were most impacted by the initial arrivals.

The arrival in Oklahoma wasn't the end of the Trail of Tears. It was the beginning of a centuries-long fight for the right to exist on the land they were promised. Understanding that distinction is the difference between knowing a fact and understanding history.