Walk through the streets of Asmara on a Sunday morning and you'll see it. It’s hard to miss. Amidst the Art Deco architecture and the scent of roasting coffee, there is a specific, shimmering whiteness that defines the landscape. This is the traditional dress of Eritrea. It isn't just a costume for a museum or a relic of the past. It's alive. While many cultures have swapped their ancestral garments for fast-fashion hoodies and jeans, Eritreans have held onto the Zuria and the Kidan Habesha with a grip that borders on the sacred. Honestly, it’s one of the few places where the ancient feels more fashionable than the new.

Identity is a tricky thing. For a nation that fought for decades for its independence, what you wear isn't just a style choice; it’s a political statement and a cultural anchor. The white cotton cloth—woven by hand, often by male weavers known as Shemane—represents a continuity of history that predates modern borders.

The Fabric of the Zuria and Why White is Everything

You’ve probably noticed that almost every traditional Eritrean outfit is white. This isn't an accident. In the Eritrean highlands, white symbolizes purity, peace, and the divine. The fabric itself is called Shemma. It’s a thin, hand-spun cotton that feels surprisingly light but offers enough warmth for those chilly Highland nights.

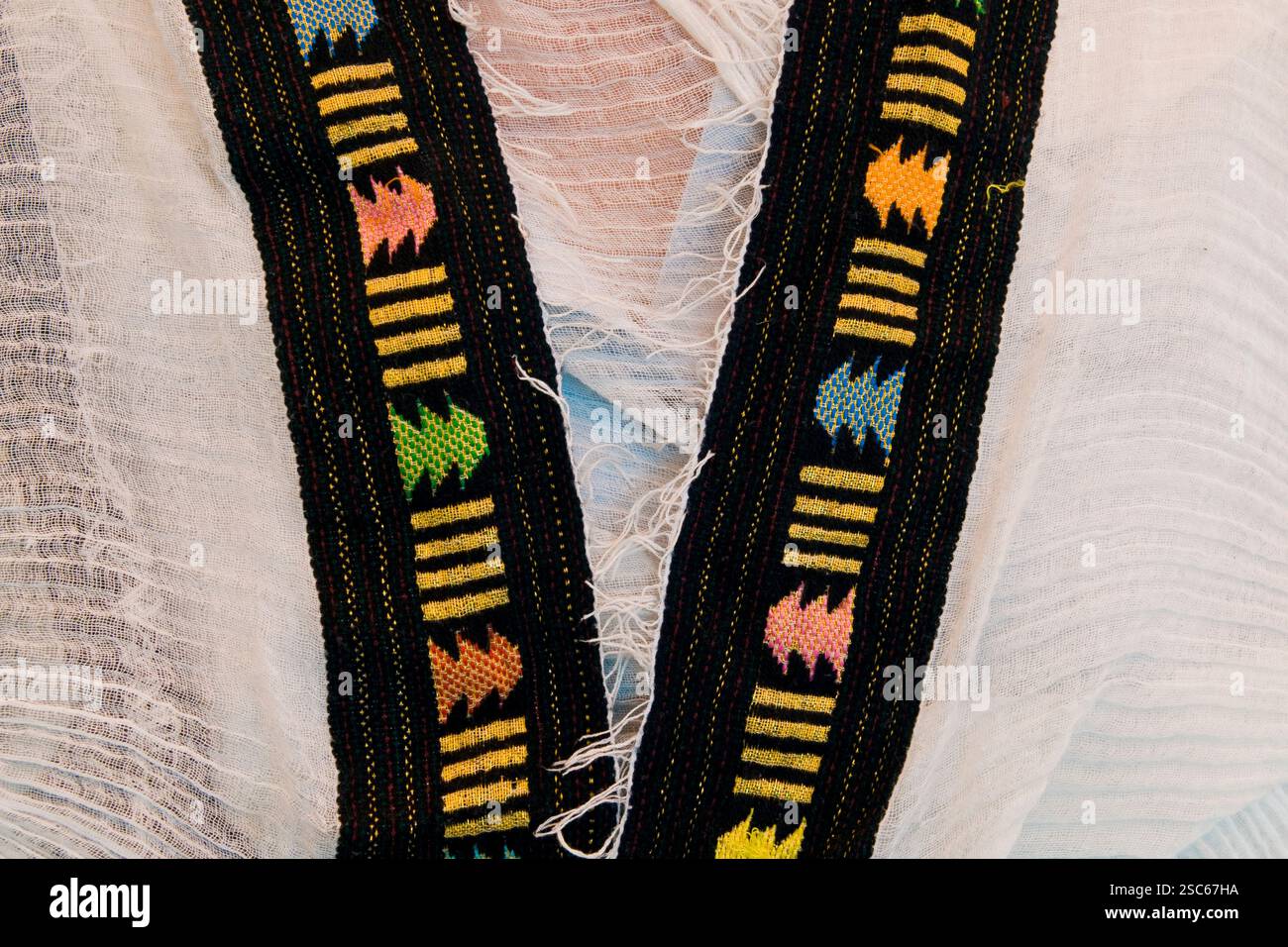

There’s a nuance here most people miss. Not all white dresses are created equal. A true traditional dress of Eritrea is defined by the Mek'ennet (a belt) and the Netela (a delicate shawl). The Netela is basically the Swiss Army knife of Eritrean fashion. Depending on how you drape it—over one shoulder, both shoulders, or over the head—you are communicating your social status or your mood. If you’re at a funeral, you wear it one way. At a wedding? Completely different. It’s a silent language.

The embroidery, or Tilet, is where the personality comes in. This is the colorful border that runs along the edges of the dress and the shawl. In the past, these patterns were relatively simple, but walk into a boutique in the Gejeret neighborhood today and you’ll see neon pinks, deep golds, and intricate geometric shapes that take weeks to stitch. It's a massive industry.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

The Men’s Version: Simplicity and Authority

Men don’t get left out, though their kit is a bit more straightforward. They wear the Kidan Habesha, which usually consists of white trousers and a long-sleeved shirt that reaches the knees. But the real power move is the Gabi.

The Gabi is a much heavier, multi-layered cotton wrap. Think of it as a wearable weighted blanket. It’s thick, it’s warm, and it’s what an elder wears when they are sitting in a communal meeting or "Baito." When a man wraps a Gabi around himself, he’s projecting a sense of authority and calm. It’s the ultimate comfort wear, honestly.

It’s Not Just One Look: Ethnic Diversity in Eritrean Fashion

Wait. We need to stop for a second. Most people outside the Horn of Africa see the Zuria and think that's the whole story. It’s not. Eritrea has nine different ethnic groups, and they don't all wear white cotton.

If you head down from the plateau toward the Red Sea coast or the western lowlands, the fashion changes completely. The Rashaida people, for example, are famous for their incredibly intricate, red and black patterned veils and dresses, often adorned with silver threads and beads. Their look is much closer to what you’d see in the Arabian Peninsula, reflecting their migratory history.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

- The Tigre and Nara: Their styles often incorporate bold colors and different head-wraps.

- The Kunama: Known for using vibrant beads and handmade jewelry that tell stories of lineage.

- The Afar: Their traditional attire is built for the heat of the Danakil Depression, focusing on wraps that allow for airflow while protecting the skin from the brutal sun.

This diversity is what makes the traditional dress of Eritrea so complex. It’s a mosaic. A Tigrinya woman from Mendefera will look nothing like a Hidareb woman from the north, yet both are quintessentially Eritrean.

The Hair: The Shuruba is the Final Touch

You cannot talk about the dress without talking about the hair. The Shuruba (braiding) is an art form that rivals the weaving of the cloth itself. These aren't just braids; they are architectural feats.

The patterns often indicate whether a woman is married, single, or in a state of mourning. For example, the Albaso style involves thick braids that run from the forehead to the nape of the neck, creating a crown-like effect. It’s often paired with a small gold or silver ornament called a Tellal. If you’re attending a Melsi (the second day of a wedding celebration), the hair is just as important as the dress. It can take hours—sometimes a whole day—to get it right. It’s a social event in itself, with women gathering to braid, talk, and drink coffee.

The Modern Shift: From Hand-Loom to High Fashion

Is the tradition dying? Not even close. If anything, it’s evolving. Designers like Milen Emnaye and others in the diaspora are taking the Tilet patterns and putting them on modern silhouettes. You’ll see the traditional embroidery on evening gowns, business suits, and even sneakers.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

However, there is a tension there. The "authentic" traditional dress of Eritrea is expensive. A hand-woven, custom-embroidered Zuria can cost hundreds, even thousands of dollars. Because of this, the market has been flooded with cheaper, machine-made versions imported from abroad. Purists hate them. They say the machine-made fabric doesn't "breathe" like the hand-spun cotton. They’re right, but for the younger generation in the diaspora, these affordable versions are a way to stay connected to their roots without breaking the bank.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Cotton

There's a common misconception that this cotton is fragile. It’s actually surprisingly durable. But you can't just toss a Zuria in a modern washing machine with a tide pod. That’s a recipe for disaster.

The traditional way to clean these garments involves a specific root called Soddo. It acts as a natural detergent that keeps the white fabric bright without the harshness of bleach. If you use bleach on a hand-woven Zuria, the cotton fibers will eventually turn yellow and brittle. It’s all about the chemistry of the natural fibers.

Practical Tips for Sourcing and Wearing Eritrean Traditional Attire

If you're looking to buy or commission a piece, don't just go for the first thing you see online. Here is how you actually handle this.

- Check the weight: Hand-spun cotton (Eti) has a slight irregularity to it. It feels "alive" and has a bit of weight despite being thin. If it feels like a standard bedsheet, it's machine-made.

- Inspect the Tilet: Look at the back of the embroidery. On a high-quality dress, the stitching on the back is almost as clean as the front.

- The Netela test: A real Netela should be sheer enough to see through but strong enough not to tear when you drape it.

- Fit matters: These dresses are meant to be voluminous but cinched at the waist. If it’s not tailored to your height, the embroidery at the bottom (the Zanf) will get ruined on the floor.

Eritrean fashion is a massive point of pride. It survived the colonial era, it survived the war, and it's currently surviving the digital age. When you put on these clothes, you aren't just getting dressed. You’re wearing a story that is thousands of years old, yet still somehow perfect for a wedding in 2026.

To truly respect the craft, look for pieces made by local weavers in Asmara or Keren. Supporting the Shemane ensures that the skill of hand-weaving doesn't vanish. If you own a piece, store it rolled, not folded, to prevent the delicate cotton fibers from breaking along the crease lines over time. This ensures the garment remains an heirloom rather than a one-time outfit.