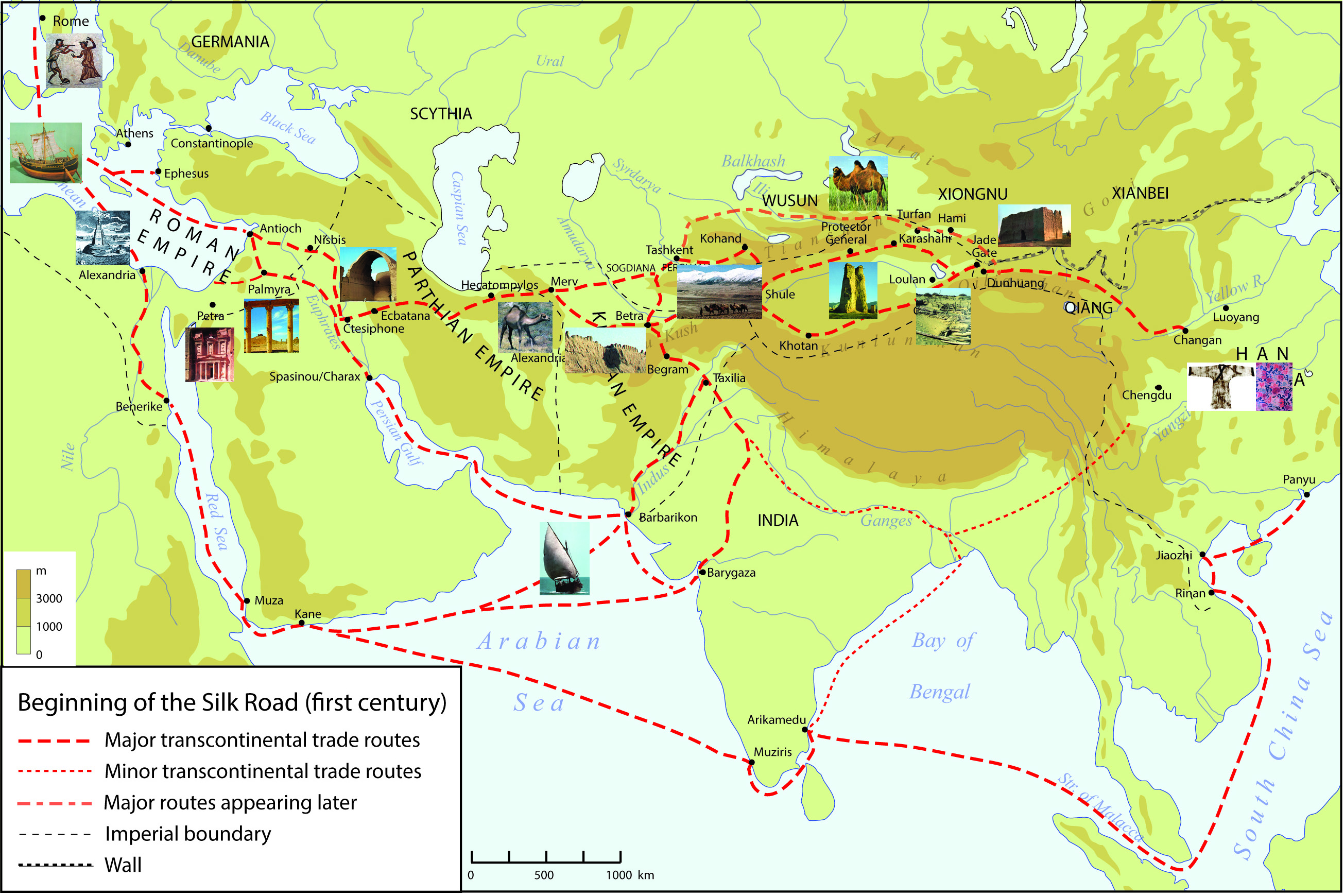

If you look at a modern route of the silk road on map, you might expect a single, bold line connecting Rome to Xi'an. It wasn’t like that. Honestly, the "Silk Road" is a bit of a marketing gimmick coined by a German geographer named Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877. He called it Seidenstraße. Before that? It was just "the road to Samarkand" or "the way east." It was a massive, shifting web of trails, mountain passes, and sea lanes that didn't just carry silk, but also plague, religion, and the secret to making paper.

People often get the geography wrong. They think it's just a straight shot through the desert. In reality, the route of the silk road on map looks more like a nervous system than a highway.

Where the journey actually started

Most historians agree the eastern terminus was Chang'an, which we now call Xi'an. If you go there today, you can still see the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, built to house the Buddhist sutras that the monk Xuanzang brought back from India via these very trails. From Xi'an, the path squeezed through the Hexi Corridor. This was a narrow string of oases tucked between the massive Gobi Desert and the high Tibetan Plateau. It was a bottleneck. If you controlled the Hexi Corridor, you controlled the world’s wealth.

Then things got complicated. Once you hit Dunhuang, the map splits like a frayed rope.

The Taklamakan Desert is one of the most inhospitable places on the planet. Its name roughly translates to "go in and you won't come out." Merchants had to choose: do you go north of the desert or south? The northern route hugged the Tianshan Mountains, passing through places like Turpan. The southern route skirted the Kunlun Mountains. Both were terrifying. You weren't traveling in a vacuum; you were moving from one "micro-state" to another, paying protection money to local warlords and hoping your camels didn't die of thirst.

The Central Asian Hubs: Why Samarkand is the key

If you’re tracing the route of the silk road on map, the absolute centerpiece is Central Asia—modern-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. This was the land of the Sogdians. You’ve probably never heard of them, but they were the middle-men of the ancient world. They were the ones actually moving the freight while the Chinese and Romans just sat at either end wondering where their luxury goods were coming from.

🔗 Read more: The Eloise Room at The Plaza: What Most People Get Wrong

Samarkand and Bukhara weren't just stops. They were the New York and London of the 8th century.

- Samarkand: Known for its blue-tiled mosques and as the capital of Timur's empire.

- Merv: Once the largest city in the world before the Mongols leveled it in 1221.

- The Pamir Mountains: Often called the "Roof of the World," this was the most grueling climb for any caravan.

The geography here dictated everything. You couldn't just "drive" through. You waited for seasons to change. You waited for wars to end. Sometimes a caravan would sit in a Caravanserai (ancient roadside inns) for months. These buildings were spaced about 20 to 30 miles apart—the distance a camel can walk in a day. You can still see the ruins of these stone forts dotting the map from Turkey to Western China.

Mapping the sea: The maritime silk road

We can't just talk about dirt and camels. A huge chunk of the route of the silk road on map happens in the water.

While the land routes were getting dangerous due to the decline of the Abbasid Caliphate or the rise of the Mongols, the sea routes exploded. This "Maritime Silk Road" connected Quanzhou in China to Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, and the Persian Gulf. This is how spices moved. Nutmeg, cloves, and pepper were often more valuable than silk.

The ships—junks and dhows—relied entirely on the Monsoon winds. If you timed it wrong, you were stuck in a foreign port for six months waiting for the wind to blow the other way. This forced a massive cultural exchange. Arab traders lived in China; Chinese sailors lived in India. It wasn't just trade; it was a total blurring of borders.

💡 You might also like: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the map shifted over time

Maps aren't static. The route of the silk road on map changed based on who was winning which war. When the Han Dynasty was strong, the road was safe. When the Roman Empire collapsed, the demand for silk in the West plummeted, and the routes withered.

The biggest shift came with the Mongol Empire.

Genghis Khan and his successors did something wild: they put the entire route under one administration. This was the Pax Mongolica. For a brief window in the 13th and 14th centuries, a traveler like Marco Polo could walk from Venice to Beijing with a "paiza" (a golden tablet that acted as a VIP passport) and not get robbed. It was the first time the map was truly "open." But that same openness allowed the Black Death to travel from the steppes of Central Asia to the ports of Europe, killing off a third of the population. Trade has a dark side.

The Persian and Anatolian stretch

As the routes moved west from Central Asia, they converged in Rayy (near modern Tehran) and then headed toward Baghdad. Baghdad was the intellectual heart of the road. While Europe was in the Dark Ages, the House of Wisdom in Baghdad was translating Greek texts into Arabic, funded by the taxes levied on Silk Road trade.

Finally, the goods reached Constantinople (Istanbul) or Antioch. This was the finish line for the Eastern goods and the starting line for European merchants. The Silk Road didn't "end" at a wall; it dissolved into the Mediterranean Sea.

📖 Related: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

Realities of the journey (What the maps don't show)

- Average speed: 15-20 miles per day.

- Total distance: Roughly 4,000 miles.

- The "Cargo": It wasn't just silk. It was cobalt for blue porcelain, horses from the Fergana Valley, and glass from Rome.

- The Language: Sogdian was the lingua franca for centuries, later replaced by Persian and Turkic dialects.

Modern-day implications: The Belt and Road

You can't look at a route of the silk road on map today without seeing the "New Silk Road" or the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China is spending trillions to rebuild these ancient corridors with high-speed rail and deep-water ports. They are literally paving over the old camel tracks with asphalt and steel.

Places like Khorgos, a massive "dry port" on the border of Kazakhstan and China, are the new Samarkands. It’s a surreal landscape of cranes and shipping containers in the middle of a desert where nomads used to graze sheep. The geopolitics haven't changed much; it's still about who controls the gates between the East and the West.

How to use this knowledge

If you're a traveler, researcher, or just a map nerd, understanding these routes requires looking past the lines.

- Check the topography: Open Google Earth and look at the Khyber Pass or the Wakhan Corridor. You’ll quickly see why the roads went where they did. Geography was destiny.

- Visit the "Second Cities": Don't just go to Xi'an or Istanbul. Visit Khiva in Uzbekistan or Merv in Turkmenistan. These are the "ghost" nodes of the map that offer the most authentic glimpse into the past.

- Follow the DNA: The Silk Road is visible in the people. You'll find blue-eyed Tajiks and Chinese-looking Hazaras in Afghanistan. The map is written in the genetics of the people living along these routes.

- Trace the religion: Look at how Buddhism moved from India to Japan, or how Islam moved from Arabia to Indonesia. The map of world religions is almost an exact overlay of the Silk Road trade routes.

The Silk Road was never a place. It was a process. It was the first time the world became "global," and even though the camels are gone, the paths they wore into the earth still dictate where the world’s power flows today.