Christopher Columbus didn't have GPS. He didn't even have a reliable way to measure longitude, which is basically why he ended up thousands of miles from where he thought he was. When you look at a map of Columbus voyages, you aren't just looking at lines on water; you're looking at a series of massive, expensive, and often desperate guesses.

People think it was just one trip. It wasn't. It was four separate slogs across the Atlantic between 1492 and 1504. Each one had a different vibe, a different goal, and a progressively more stressed-out Columbus trying to prove he hadn't just found a bunch of islands in the middle of nowhere.

The First Path: 1492 and the "Oops" Factor

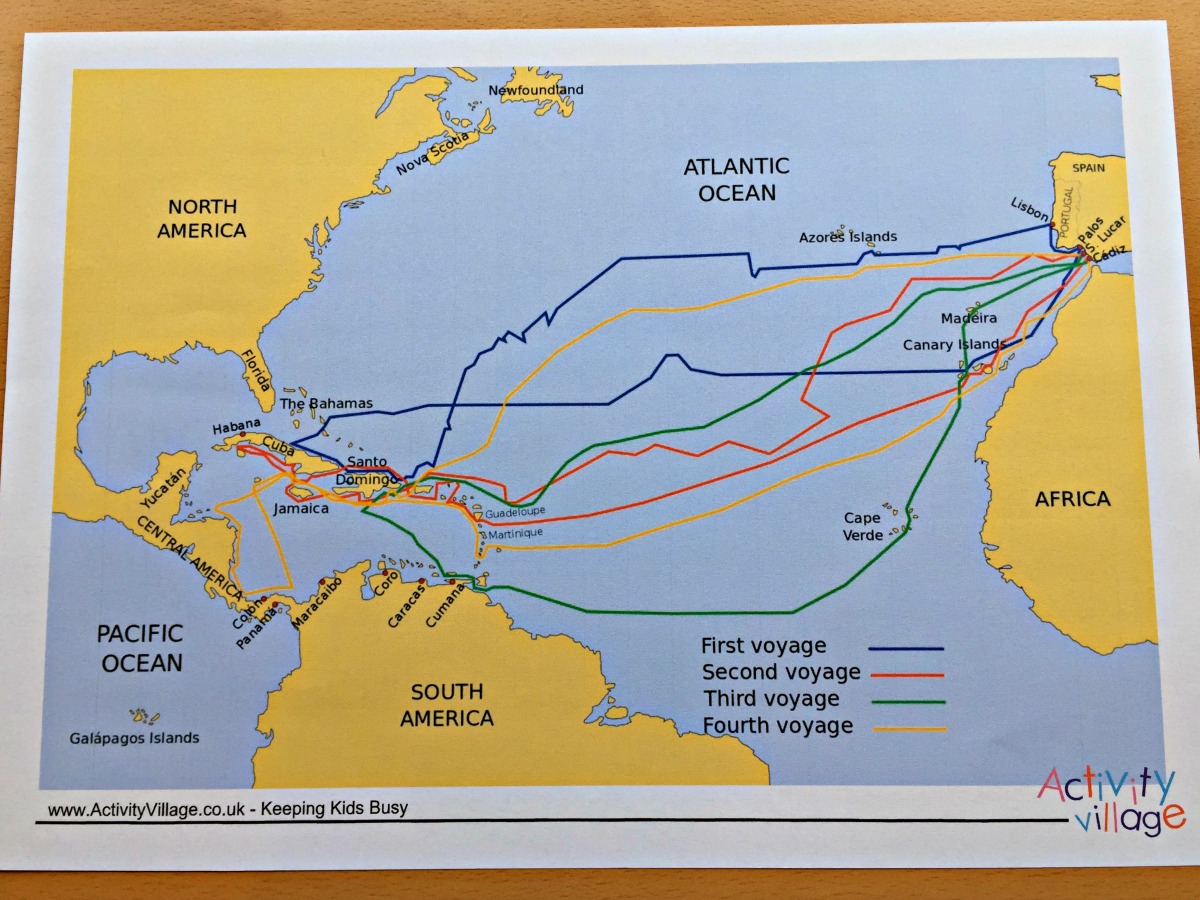

The first line on any map of Columbus voyages is the one everyone knows. He left Palos de la Frontera in August 1492. He stopped at the Canary Islands—this was crucial—because he needed the trade winds. He basically hitched a ride on the North Equatorial Current.

It took five weeks. Imagine sitting on a wooden boat for five weeks with no idea if the world ends or if you're about to hit Japan. On October 12, they hit the Bahamas. Columbus called the island San Salvador, though historians like Samuel Eliot Morison have spent decades arguing over which specific island it actually was (Waitling Island is the top contender).

He then cruised around Cuba and Hispaniola. He lost his flagship, the Santa Maria, because it ran aground on Christmas Day. Not a great holiday. He had to leave 39 men behind in a fort called La Navidad, which, spoiler alert, didn't end well for them. The return trip on the map of Columbus voyages shows him swinging north to catch the westerlies. He knew how to use the wind. He was a brilliant sailor, even if his geography was a mess.

🔗 Read more: The Eloise Room at The Plaza: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the Second Voyage Looked So Different

By 1493, Columbus wasn't a dreamer; he was a celebrity. He had 17 ships and 1,200 men. This wasn't an exploration; it was a colonization effort.

If you trace the second route, you’ll see it’s much further south than the first. He hit the Lesser Antilles—Dominica, Guadeloupe, and Antigua. He was looking for his men at La Navidad. When he got there, the fort was burned and everyone was dead.

This voyage is where the map gets messy. He spent a lot of time poking around the southern coast of Cuba. He actually made his crew sign a document swearing that Cuba was the mainland of Asia. If they disagreed, they’d be fined or have their tongues cut out. That's one way to handle peer review. Honestly, he was obsessed with the idea that he was near the Ganges River.

The Third Voyage and the Continental Realization

1498 was the year things got weird. Columbus went even further south, hitting Trinidad and the coast of present-day Venezuela.

💡 You might also like: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

This is the most important part of the map of Columbus voyages because he finally hit a continent. He saw the Orinoco River dumping massive amounts of fresh water into the ocean. He realized this couldn't just be another small island. In his diary, he started getting mystical, suggesting he might have found the literal Garden of Eden.

While he was finding South America, his colony in Hispaniola was falling apart. The settlers hated him. He was a "terrible" manager. Eventually, a royal commissioner named Francisco de Bobadilla showed up, arrested Columbus, and sent him back to Spain in chains.

The Fourth Voyage: The "High Voyage" of 1502

He talked his way back into one last trip. He was old, sick with what we think was reactive arthritis, and his eyes were constantly bleeding. He called this the Alto Viaje.

The map of Columbus voyages for this final stint shows him hugging the coast of Central America—Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. He was looking for a strait to the Indian Ocean. He spent months battling storms. He actually stayed in Panama for a while, hearing rumors of "another sea" just a few days' walk away. He was this close to the Pacific, but the jungle and the hostile interactions with the local Ngäbe people forced him back.

📖 Related: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

He ended up shipwrecked on Jamaica for a year. A year! He only got saved because he used a lunar eclipse to trick the local indigenous population into giving them supplies. He finally got back to Spain in 1504, just weeks before his patron, Queen Isabella, died.

Mapping the Misconceptions

- He didn't prove the earth was round. Most educated people in 1492 already knew that. The Greeks had figured it out centuries prior. Columbus’s "innovation" was actually a mistake: he thought the earth was much smaller than it is.

- The "Map" was never static. Every time he returned, the cartographers in Europe, like Juan de la Cosa, had to redraw everything.

- He never actually set foot on what is now the United States. Not once. His map stays firmly in the Caribbean and Central/South America.

The Real Legacy of the Nautical Charts

When we look at the map of Columbus voyages today, we see the start of the Columbian Exchange. This isn't just about ships; it's about the movement of potatoes, tomatoes, horses, and, unfortunately, smallpox.

The routes he mapped became the "Spanish Main." For the next 300 years, the path he carved across the Atlantic was the primary highway for the Spanish silver fleets. He mastered the North Atlantic Gyre—that circular system of currents that basically dictated global trade until the steam engine.

If you’re trying to visualize these routes for a project or just because you’re a history nerd, look for the "Dead Reckoning" methods they used. They used a compass, a half-hour sandglass, and a lead line to check depth. No longitude. Just guts and a lot of luck.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

- Visit the Archivo General de Indias: If you’re ever in Seville, Spain, this is the holy grail. It houses the actual documents and maps relating to the voyages.

- Study the Piri Reis Map: For a fascinating counter-perspective, look at this 1513 Ottoman map. It supposedly used some of Columbus’s lost charts as a source.

- Use Digital Mapping Tools: Websites like Native Land Digital can be layered over a map of Columbus voyages to see exactly whose ancestral lands he was "discovering" in real-time.

- Compare the Voyages: Don't treat them as one event. Separate the 1492 landing from the 1498 continental discovery to understand how his own perception of the world changed as he aged.

The maps tell a story of a man who was a genius on the deck of a ship and a complete disaster on land. By separating the four routes, you see the transition from a hopeful explorer to a desperate, stranded man trying to salvage his reputation in the Jamaican sand.