You’re breathing right now. It’s automatic. You don't think about the air moving past your throat, down through that rigid pipe in your neck, and into your lungs. But honestly, the definition of the trachea is way cooler than "just a breathing tube." It’s a specialized piece of biological engineering that keeps you from choking on dust or collapsing your airway every time you take a deep breath.

It’s the windpipe. That’s the common name.

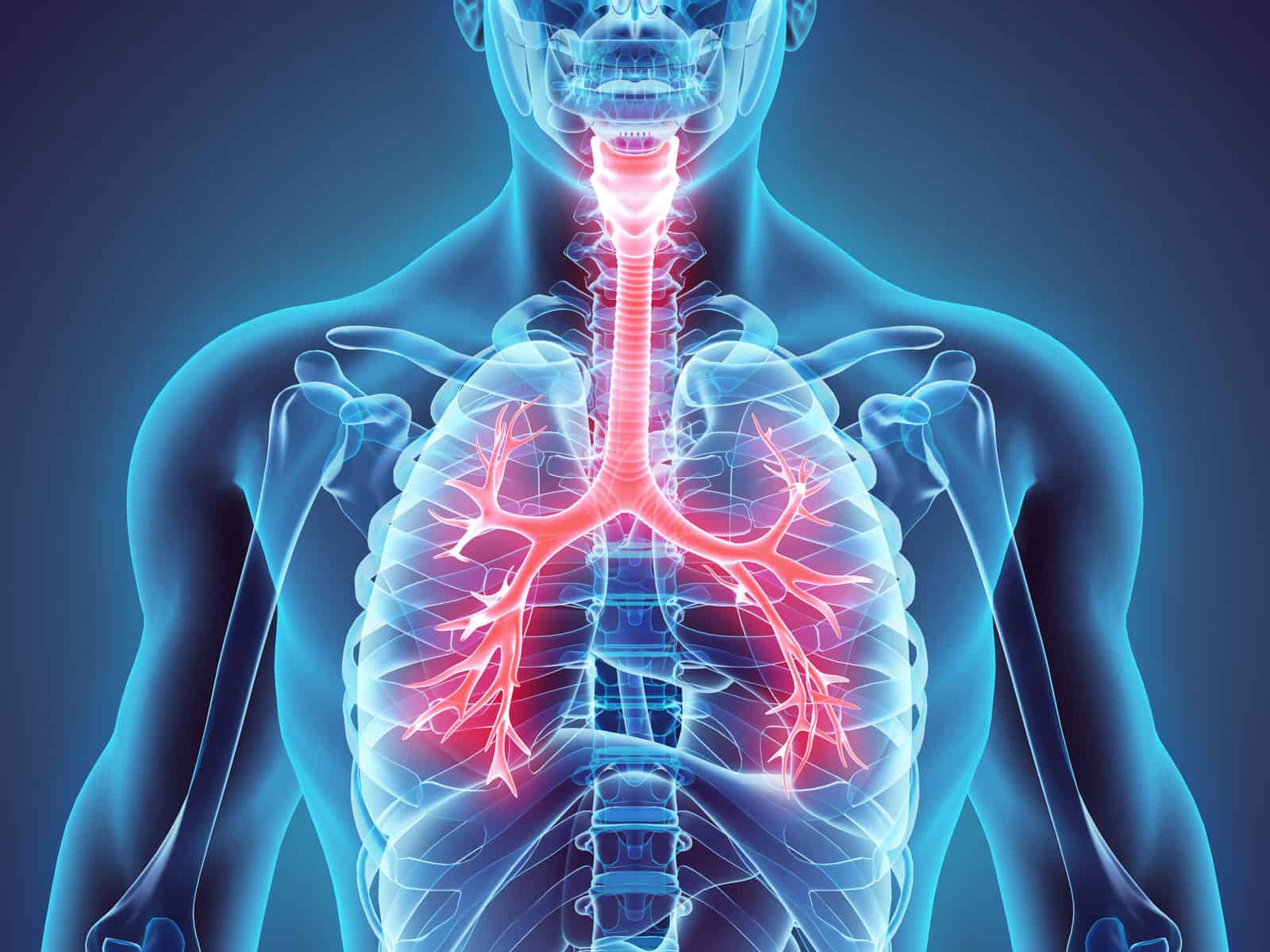

Biologically, though, it’s a fibrocartilaginous tube. It sits right in the midline of your lower neck and upper thorax. If you run your fingers down the front of your neck, you can feel those hard, bumpy ridges. Those are the tracheal rings. They aren't there for decoration. They are D-shaped or C-shaped loops of hyaline cartilage that stop your airway from flopping shut like a wet straw when you inhale.

What is the Trachea, Exactly?

Let’s get technical for a second but keep it real. The definition of the trachea describes a conduit that starts at the inferior margin of the larynx—the voice box—and extends down to the carina. The carina is this little internal ridge where the trachea decides to split into two, becoming the left and right primary bronchi.

It’s surprisingly short. Most people think it’s this long, sprawling organ, but in an average adult, it’s only about 10 to 11 centimeters long. That’s roughly four inches. It’s about the width of your thumb.

Structure matters here.

The front and sides are tough. That’s the cartilage. But the back? The posterior wall is flat and soft. It’s made of the trachealis muscle. Why? Because your esophagus—the tube for your food—sits right behind it. When you swallow a huge bite of a sandwich, your esophagus needs room to expand. If the trachea were a solid, 360-degree circle of bone-hard cartilage, you’d probably choke every time you ate a bagel. The soft back of the trachea lets the food pipe bulge forward slightly. It’s a space-saving design.

How it Actually Works (The Mucociliary Escalator)

Think of your trachea as a high-tech air filtration system. It isn't just a passive pipe. The inside is lined with a moist layer called the mucosa. This layer is covered in tiny, microscopic hairs called cilia.

These cilia move. They beat in a coordinated wave, like fans at a stadium doing "the wave," but they move upward.

They’re pushing mucus toward your throat.

This is the mucociliary escalator. When you breathe in dust, pollen, or nasty bacteria, it gets stuck in the sticky mucus lining your trachea. The cilia then "escalate" that junk up to your pharynx. Once it hits the back of your throat, you either cough it out or—more likely—you swallow it without even realizing it. Your stomach acid then destroys the invaders.

If you smoke, these cilia get paralyzed. They stop moving. This is why long-term smokers have that "smoker's cough" in the morning. Their body is trying to manually hack up all the gunk that the paralyzed cilia failed to move during the night.

Why the Trachea Fails: Common Medical Realities

Sometimes the system breaks. It’s scary when it does because, well, you need to breathe.

One of the most common issues is tracheomalacia. This is basically a "floppy" trachea. The cartilage rings that are supposed to keep the airway open are weak or damaged. In babies, it’s often something they’re born with and eventually outgrow. In adults, it can happen after long-term intubation or chronic inflammation. When they breathe out, the pipe collapses. It sounds like a harsh, barky cough or a high-pitched wheeze called stridor.

Then there’s tracheal stenosis. This is a narrowing of the tube. Usually, it’s caused by scar tissue. If you’ve been on a ventilator for a long time, the pressure from the cuff of the breathing tube can irritate the tracheal wall. Your body tries to heal itself by building scar tissue, but that tissue can narrow the airway until it’s like trying to breathe through a cocktail straw.

It’s serious stuff.

Doctors like Dr. Gaetano Rocco and other thoracic specialists often have to use stents—little mesh tubes—to prop the airway open, or even perform a tracheal resection to cut out the scarred part and sew the healthy ends back together.

The Anatomy of a Cough

A cough is basically a high-pressure blast through your trachea. When something irritates your airway, your vocal cords close tight. Your abdominal muscles and diaphragm contract hard, building up massive pressure in your chest.

✨ Don't miss: Dr Scholl's Shoes Inserts: What Most People Get Wrong

Then, the vocal cords snap open.

The air rushes out of the trachea at speeds up to 50 miles per hour. This violent gust is designed to dislodge whatever shouldn’t be there. Because the back of the trachea is muscular (the trachealis muscle we talked about), it can actually contract during a cough to narrow the opening. This narrowing increases the velocity of the air—sort of like putting your thumb over the end of a garden hose to make the water spray further.

Fascinating Tracheal Facts Most People Miss

- It moves: Your trachea isn't bolted in place. When you swallow or move your neck, it slides up and down. It’s quite flexible.

- The Carina is sensitive: The spot where the trachea splits is one of the most sensitive areas in your body. If a piece of food or even a drop of water touches the carina, it triggers a massive, uncontrollable coughing fit. It's your body's last-line "alarm system" to protect the lungs.

- It’s not perfectly straight: It usually tilts slightly to the right as it descends because the arch of the aorta (the big artery coming off your heart) pushes against it on the left side.

- Dead Space: In respiratory therapy, the trachea is part of "anatomical dead space." This is air you inhale that never reaches the alveoli where oxygen exchange happens. It just sits in the pipes.

Protecting Your Airway

Understanding the definition of the trachea makes you realize how fragile and vital this four-inch tube really is. It’s the gateway to your life force.

To keep it healthy, hydration is actually key. The mucociliary escalator only works if your mucus is thin and slippery. If you’re dehydrated, that mucus gets thick and "tacky," making it harder for the cilia to move it. This is why you feel so congested and "stuck" when you have a cold and haven't had enough water.

Also, avoid inhaling irritants. Fumes, heavy dust, and especially cigarette smoke or vaping aerosols can cause chronic inflammation of the tracheal lining. Over time, this leads to squamous metaplasia—where the delicate, hairy cells turn into tough, scaly cells that can't move mucus. That’s a one-way ticket to chronic bronchitis.

📖 Related: GLP-1 Dose Conversion Chart: What Most People Get Wrong About Switching Meds

Actionable Next Steps for Respiratory Health

If you’re worried about your tracheal health or find yourself coughing more than usual, start with these steps:

- Monitor for Stridor: This is a high-pitched whistling sound when you breathe in. It’s different from a wheeze (which usually happens when you breathe out). If you hear a whistle when inhaling, see a doctor immediately. It signals an upper airway obstruction.

- Hydrate for Mucus Health: Aim for consistent water intake to keep the tracheal lining moist. This allows the cilia to effectively clear out pollutants you breathe in daily.

- Check Your Posture: While it sounds weird, chronic "tech neck" can put weird pressure on the structures surrounding the trachea. Keep your airway "long" and unobstructed.

- Vocational Protection: If you work in construction or with chemicals, wear an N95 or a respirator. Your tracheal cilia can only handle so much silica dust or chemical vapor before they quit on you.

The trachea is a marvel of evolution. It’s a bridge between the outside world and your internal bloodstream. Respect the pipe.