You’ve likely seen it. Three wooden pegs, a handful of colorful disks, and a set of rules that seem designed to drive you absolutely up the wall.

It's the Tower of Hanoi.

Whether you first encountered it as a dusty physical toy in a doctor’s waiting room or found a version of towers of hanoi online during a late-night rabbit hole, the puzzle is a masterpiece of simplicity and psychological torture. Honestly, it’s basically just a game of moving things from Point A to Point B. But the catch—that "larger disks cannot sit on smaller disks" rule—is what turns a thirty-second task into a multi-hour obsession.

The Myth, the Monk, and the End of the World

Legend has it that in a temple in India (or sometimes Hanoi, depending on who’s telling the story), priests are working on a massive version of this puzzle with 64 golden disks. When they finish moving the entire stack to the third peg, the world will end.

Don't panic yet.

If you do the math—which a lot of bored people have—the total moves required for 64 disks is $2^{64} - 1$. That is roughly 18.4 quintillion moves. Even if these monks were moving one disk per second without ever stopping for a snack or a nap, it would take them over 580 billion years to finish. For context, our sun is expected to burn out in about 5 billion years. We've got time.

💡 You might also like: Playing A Link to the Past Switch: Why It Still Hits Different Today

The "real" history is a bit more grounded but equally clever. A French mathematician named Édouard Lucas actually invented the game in 1883. He even sold it under a pseudonym, "N. Claus de Siam," which is just an anagram for "Lucas d'Amiens." Talk about a 19th-century marketing pivot.

Why We Can't Stop Playing Towers of Hanoi Online

In 2026, you don’t need a wooden set. You can find a million versions of towers of hanoi online, ranging from sleek 3D simulations to bare-bones browser versions that look like they were coded in the 90s.

But why is it still popular?

Psychologists love this thing. It’s frequently used in neuropsychological tests to check "executive function." Essentially, it measures how well your brain can plan ahead and hold complex sequences in its working memory. When you play online, you’re basically giving your frontal lobe a treadmill workout.

The Math Is Surprisingly Elegant

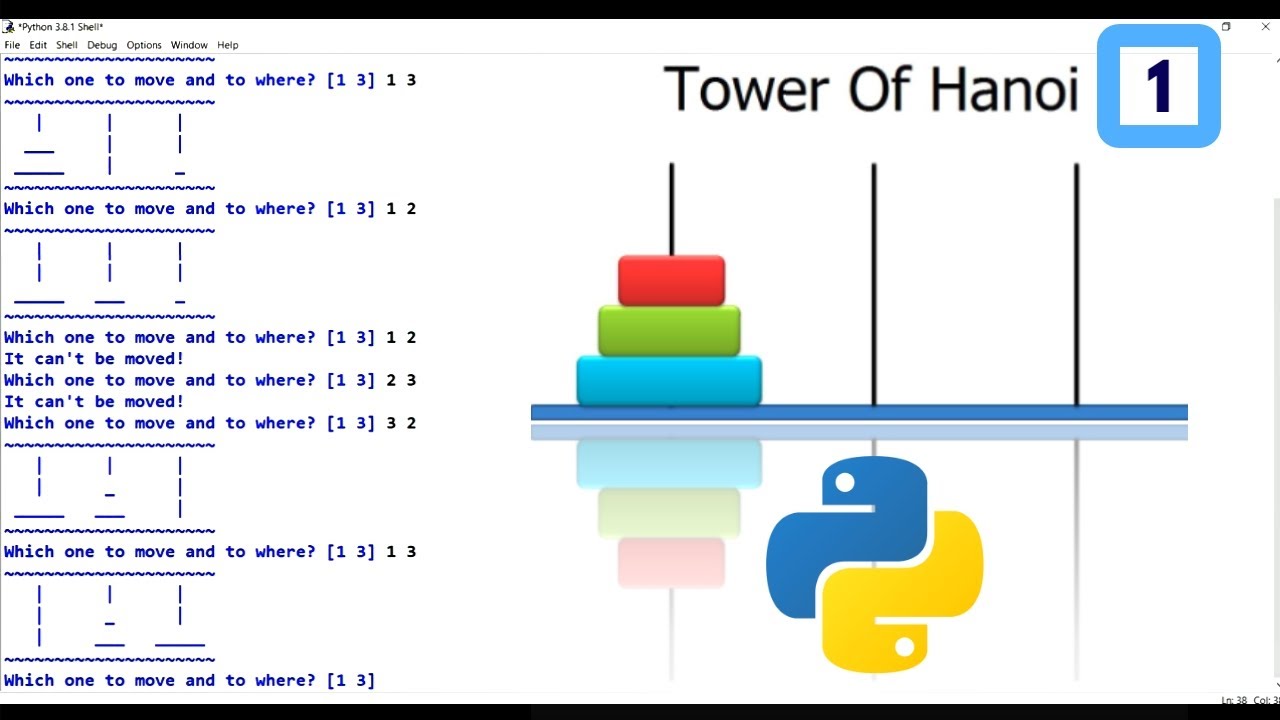

The puzzle is the "Hello World" of the coding world. If you’ve ever taken a computer science class, you probably had to write a recursive algorithm to solve it. It’s the perfect example of breaking a big, scary problem into smaller, manageable chunks.

📖 Related: Plants vs Zombies Xbox One: Why Garden Warfare Still Slaps Years Later

To move $n$ disks:

- Move $n-1$ disks to the middle peg.

- Move the biggest disk to the destination.

- Move those $n-1$ disks on top of the big one.

It sounds easy until you try it with seven disks. Suddenly, you’re 100 moves in, you realize you placed a medium disk on the wrong peg, and the whole sequence is ruined. You've got to start over. It's frustrating. It's rewarding. It's the ultimate "one more try" game.

How to Actually Win (Without Pulling Your Hair Out)

If you're playing towers of hanoi online and want to look like a genius, there’s a trick. You don't actually have to be a math prodigy to solve it quickly. There’s a pattern involving the parity (even or odd) of the disks.

For an odd number of disks:

- Move the smallest disk to the destination peg.

- Make the only other legal move available (not involving the smallest disk).

- Move the smallest disk to the next peg in the sequence.

- Repeat.

For an even number of disks:

👉 See also: Why Pokemon Red and Blue Still Matter Decades Later

- Move the smallest disk to the auxiliary (middle) peg first.

- Make the only other legal move.

- Keep that smallest disk circulating.

The smallest disk is the engine of the whole operation. It moves every second step. If you watch a speedrunner or a high-level player online, their hands (or cursors) move in a rhythmic, almost hypnotic dance. They aren't "thinking" anymore; they're just following the cycle.

Real-World Apps and Brain Benefits

It’s not just a time-waster. Scientists use the Tower of Hanoi to study everything from aging to the effects of sleep deprivation. Because the rules are so rigid, it provides a clean baseline for how the human mind approaches obstacles.

Studies from institutions like the Cognition Lab have shown that practicing these types of recursive puzzles can actually improve your "means-end analysis"—that's fancy talk for your ability to figure out which small steps you need to take to reach a distant goal.

Whether you’re a student trying to understand algorithms or just someone looking to sharpen your focus between meetings, spending ten minutes on a 5-disk or 7-disk game is surprisingly effective.

Actionable Tips for Your Next Game

If you're about to jump into a game of towers of hanoi online, keep these three things in mind to keep your move count low:

- Visualize the bottom disk first. Your entire strategy should be built around freeing that largest disk. Nothing else matters until that big guy can move to the final peg.

- Don't move the same disk twice in a row. Unless you're playing a very weird variant, moving the same disk back and forth is just wasting your time and killing your score.

- Use the "Recursive Mindset." If you get stuck, stop looking at the whole tower. Just look at the top three disks. Solve them as a mini-puzzle, then zoom out.

Ready to test your brain? Start with 3 disks to get the rhythm, then jump straight to 5. Once you can do 7 disks without making a mistake, you're officially better at planning than most of the population. Just don't try the 64-disk version unless you've got a few billion years to spare.