Tony Kaye is a name that sends a shiver down the spine of most Hollywood producers. To some, he is a misunderstood genius, a man who saw the medium of film as a canvas for high art rather than a commercial product. To others? He’s the cautionary tale of what happens when an ego outgrows the studio system. If you look at the credits of the 1998 masterpiece, you see his name. But the story of the American History X director is less about a successful film release and more about a literal war waged in the editing room.

It was his debut. Most directors would kill for a first feature starring Edward Norton at the height of his powers. Kaye, a British commercial director known for his visual flair and obsessive attention to detail, didn’t want a hit. He wanted a revolution.

What he got was a legal battle that basically defined the "Director's Jail" phenomenon for the next decade.

The Man Who Tried to Erase His Own Name

The central conflict of American History X isn't just on the screen. It was behind the lens. After Kaye turned in his first cut, New Line Cinema and Edward Norton felt the movie needed more—more character development, more breathing room, more of Norton. Kaye disagreed. Vehemently.

He didn't just send a few angry emails. Kaye spent $100,000 of his own money on full-page ads in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. He used these ads to trash his own film, his actors, and the studio executives. He called Norton a "narcissist" and the studio’s cut a "shambles."

At one point, the American History X director even demanded that his name be removed from the credits and replaced with "Humpty Dumpty." The Directors Guild of America (DGA) said no. Their reasoning was simple: if you trash a movie publicly, you lose the right to use a pseudonym like Alan Smithee. Kaye sued the DGA and the studio for $200 million. He lost.

Honestly, it’s one of the most self-destructive streaks in the history of cinema. You have a film that is destined for Oscar nominations—Norton eventually got one—and you’re out here trying to bury it before it even hits theaters.

Why the "Norton Cut" Won

There are two versions of this movie that exist in the ether. There is Kaye’s original 95-minute cut, which he describes as fast-paced and "punk rock." Then there is the 119-minute theatrical version, often referred to as the "Norton Cut" because the actor reportedly spent weeks in the editing suite refining it.

💡 You might also like: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Most critics who have caught glimpses of the earlier versions or read the scripts suggest that Kaye’s version was colder. It was less about the redemptive arc of Derek Vinyard and more about the brutal, cyclical nature of violence. Norton’s influence brought out the humanity. It made the tragedy of the ending land harder because we spent more time watching the family dynamic.

Kaye hated it. He felt the emotionality was manipulative. He wanted something harder, drier, and more experimental.

The irony? The theatrical version is widely considered one of the greatest films of the 90s. It’s a staple in film schools and social studies classrooms. Kaye’s "disaster" became a masterpiece, but he refused to take the win.

A Career Defined by "What If?"

Tony Kaye didn't just stop at American History X. His reputation followed him like a shadow. He spent years working on a documentary called Lake of Fire, which is a staggeringly detailed look at the abortion debate in America. It took him 18 years to finish.

Eighteen years.

That tells you everything you need to know about his process. He isn't a "jobbing" director. He’s an obsessive. When he finally returned to narrative features with Detachment in 2011, starring Adrien Brody, the visual style was just as arresting as his debut. It had that same grainy, haunting, "Kaye-esque" look. But the bridges he burned in 1998 never quite got rebuilt.

You've got to wonder what his career would look like if he had just played the game. If the American History X director had walked onto the stage at the Academy Awards next to Norton, he might have been the next Fincher or Nolan. Instead, he became a myth. A warning.

📖 Related: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

The Visual Language of a Madman (or Genius)

Kaye’s background was in music videos and commercials. He did the famous "Intertia" ad for Nike. He did the "Runaway Train" video for Soul Asylum. He understands how to make an image stick in your brain until it hurts.

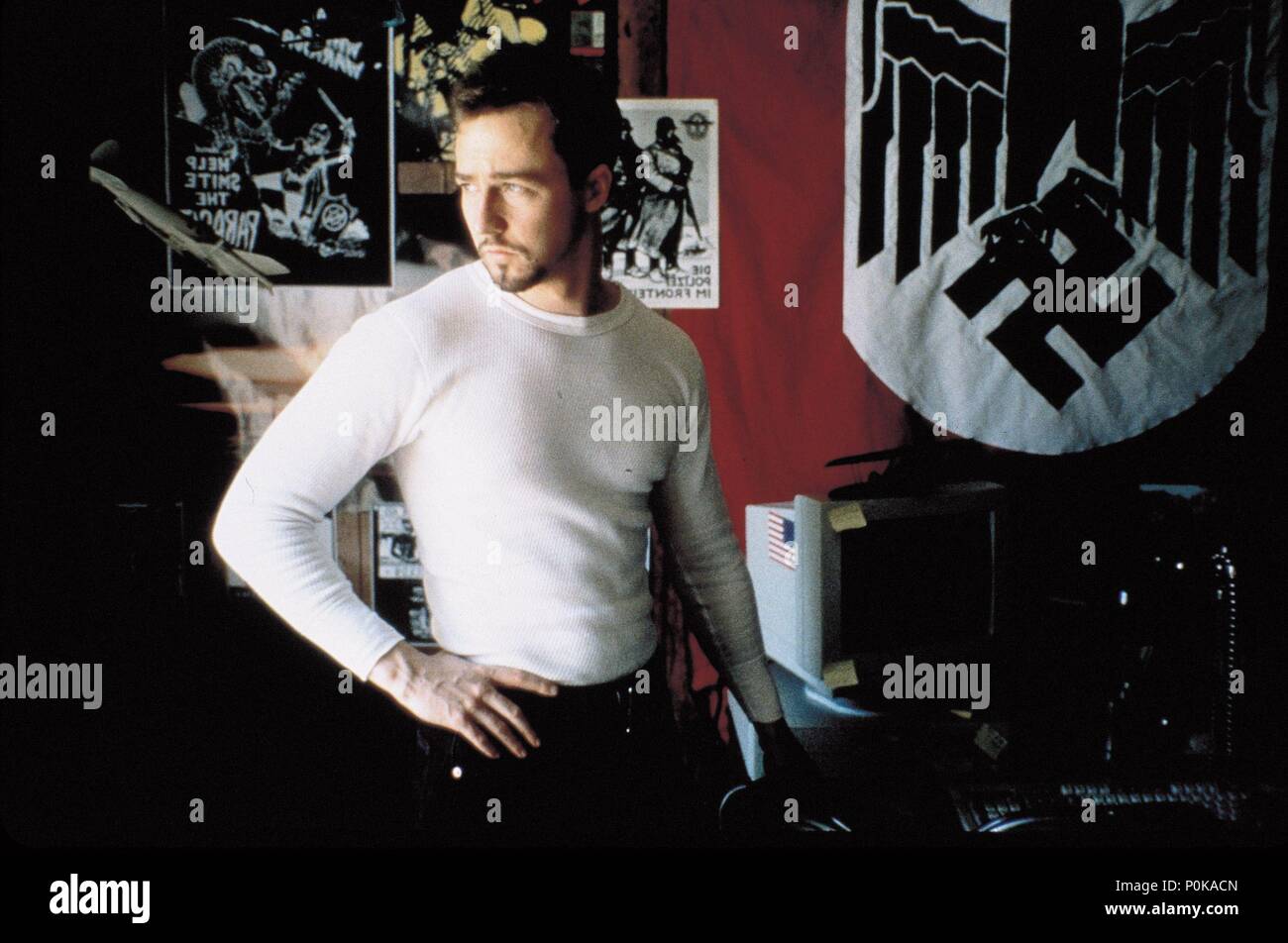

In American History X, he used black and white for the past and color for the present. It seems like a simple trope now, but the way he lit those monochrome scenes—high contrast, heavy shadows—made the neo-Nazi imagery feel like a nightmare you couldn't wake up from. He used slow motion not to make things look "cool," but to make them feel heavy.

- The Curb Stomp Scene: It's one of the most infamous moments in cinema. Kaye doesn't show the impact directly in the way a slasher flick would. He focuses on the sound and the face of Derek Vinyard. It’s the restraint that makes it horrifying.

- The Diner Scene: The lighting is sickly. It feels like a place where hope goes to die.

- The Ending: The pacing slows to a crawl, forcing the audience to sit in the discomfort of the inevitable.

Kaye’s eye is undeniable. Even when he was losing his mind during the editing process, his raw footage was so good that the studio could piece together a classic from it.

Lessons for the Modern Creator

What can we actually learn from the saga of the American History X director? It’s easy to dismiss him as a "difficult" artist, but there’s more nuance there.

First, collaboration is not a suggestion in filmmaking; it’s a requirement. Film is the only art form where you need a hundred people to agree with you to get anything done. Kaye treated it like a solo painting. He wanted total control over a medium that doesn't allow for it at the studio level.

Second, the "Final Cut" is the only thing that matters. In the age of streaming, we see "Director's Cuts" all the time (looking at you, Zack Snyder). But in 1998, once that film was printed, that was it. Kaye was fighting for his legacy in a burning building.

Actionable Insights from the Tony Kaye Saga

If you are a creator, a writer, or someone working in a collaborative industry, the Kaye story offers a blueprint of what to avoid—and what to emulate.

👉 See also: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

1. Pick Your Battles Wisely

Kaye didn't just fight for his vision; he fought everyone. He brought a priest, a rabbi, and a monk to a meeting with New Line executive Michael De Luca to "mediate." It didn't work. It just made him look unstable. If you have a creative disagreement, keep it behind closed doors. Publicly trashing your project only hurts your future funding.

2. Visual Identity is a Moat

Despite his reputation, Kaye still gets work and respect because his style is unique. People still talk about the American History X director because no one else could have shot that movie that way. Develop a "look" or a "voice" that is so distinct that people are willing to put up with your quirks just to get it.

3. Understand the Business of Art

New Line Cinema put up the money. In the world of high-stakes entertainment, the person with the checkbook usually gets the final word unless your name is Spielberg. If you want total creative freedom, you have to work at a price point where you can afford to fail. Kaye was working with a $20 million budget. That’s not "experimental indie" money.

4. The Work Outlives the Drama

Twenty-five years later, most people don't remember the Variety ads or the lawsuits. They remember Edward Norton's performance and the haunting cinematography. The work eventually stands on its own. If Kaye had just stayed quiet, he would be remembered as a titan.

Where is He Now?

Kaye is still active, mostly in the fringes. He’s always attached to five different projects that may or may not ever see the light of day. He’s a frequent speaker at film festivals, often appearing as a sort of "eccentric uncle" of the industry. He still makes art. He still challenges the status quo.

He remains the ultimate example of the "Auteur Theory" gone wrong—or right, depending on how much you value the purity of a vision over the sanity of a production.

The story of the American History X director serves as a reminder that brilliance is often a double-edged sword. To make something as raw and powerful as that film, you probably have to be a little bit obsessed. You probably have to be willing to burn it all down. But as Tony Kaye learned the hard way, once the fire starts, you can't always control which way the wind blows.

To truly understand his impact, go back and watch the film again. Ignore the behind-the-scenes drama. Look at the framing. Listen to the score. Notice how the camera lingers on the faces of the characters. That is Tony Kaye. The man who tried to take his name off the movie is the reason it’s still worth talking about today.

Next Steps for Film Enthusiasts:

To get a deeper sense of Kaye's visual style, seek out his documentary Lake of Fire. It's a grueling watch but showcases his ability to handle complex, controversial subjects without flinching. Additionally, comparing the theatrical cut of American History X with the leaked "Kaye Cut" (if you can find it in the darker corners of the internet) provides a masterclass in how much an editor can change the soul of a story.