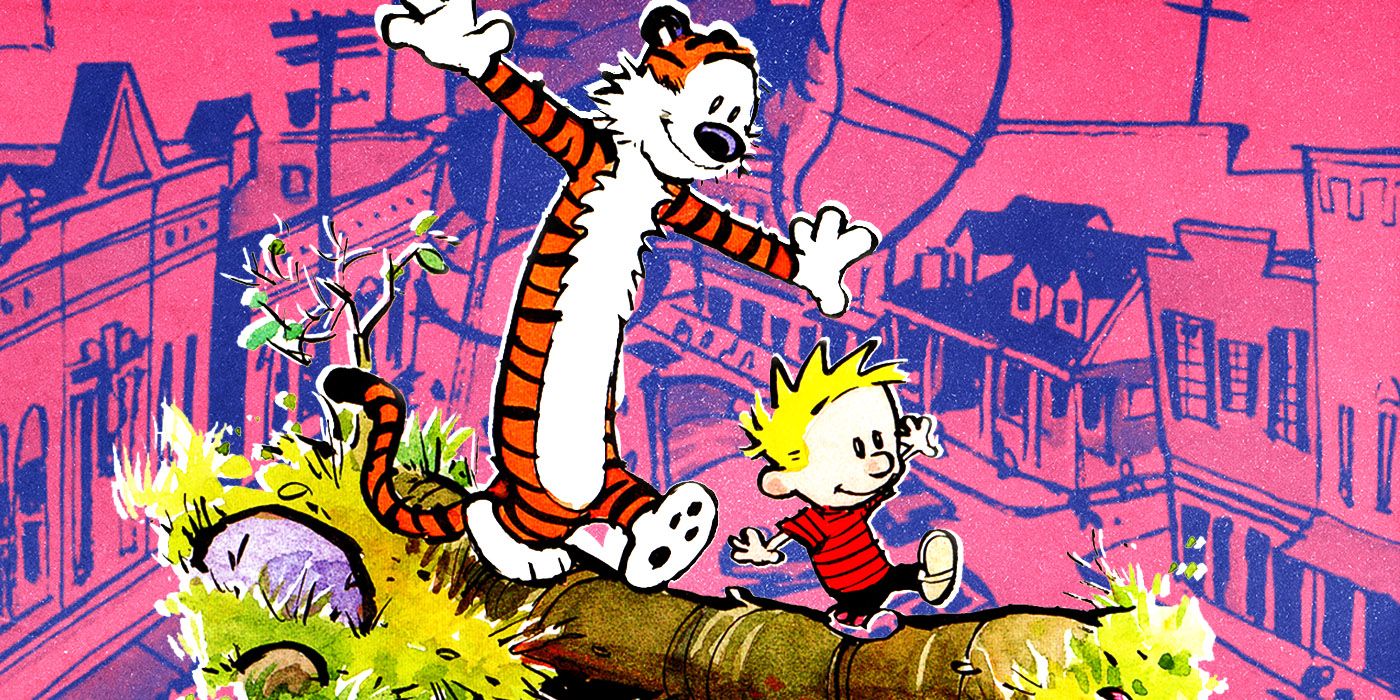

You wake up, scroll past a dozen AI-generated "lifestyle" photos, dodge a political argument, and then you see it. Maybe it’s a repost on X or a frame in your Reddit feed. It’s a six-year-old kid in a red-and-black striped shirt arguing with a stuffed tiger about the existential futility of doing math homework. It’s today on Calvin and Hobbes, and suddenly, the internet feels a little less like a dumpster fire.

There’s a weird magic to how these strips age. Bill Watterson quit the business in 1995. He walked away at the absolute peak of his powers, leaving behind a ten-year run that hasn't just survived—it has thrived in a digital world it was never meant to inhabit. Most comic strips from the '80s and '90s feel like time capsules. They mention VCRs or specific politicians. They feel dusty. But Calvin? He’s timeless because he’s basically a stand-in for every human impulse we’re told to suppress once we get a mortgage.

The Mystery of the Perpetual Rerun

If you're looking for "new" content when you search for today on Calvin and Hobbes, you aren't going to find it. Watterson is famously reclusive. He doesn't do "legacy" sequels. He didn't sell the rights to Pixar or Hallmark. What you’re seeing is a carefully curated cycle of reruns managed by Andrews McMeel Syndication.

It’s a bizarre phenomenon. We live in a culture obsessed with the "next big thing," yet millions of people start their morning by reading a comic that was drawn before the iPhone existed. Why? Because the themes are universal. One day it’s a high-speed wagon ride down a dangerous hill—a blatant metaphor for the terrifying velocity of life—and the next, it’s a quiet moment of Calvin and Hobbes looking at the stars, feeling small. It hits differently in 2026 than it did in 1986.

Honestly, the lack of new material is the strip's greatest strength. It’s a closed loop of perfection.

Why the "Today" Experience Still Hits Home

When you check out today on Calvin and Hobbes, you're participating in a ritual. In the original newspaper days, the "daily" format forced a specific pacing. Monday through Saturday were the quick hits, the snappy dialogue, the setup and punchline. Sundays were the grand canvases. Watterson famously fought his editors to get more space for the Sunday strips. He hated the "checkerboard" layout that allowed papers to cut out panels. He wanted to draw dinosaurs. He wanted Neo-Expressionist backgrounds. He wanted to turn a comic strip into high art.

You can see that struggle in the work.

Take a look at the "Spaceman Spiff" sequences. They aren't just jokes. They are visual experiments in color and perspective. When Calvin is trapped in a boring classroom, his imagination literally bleeds over the borders of the panels. It’s a visual representation of ADHD and creativity that most modern media still struggles to depict accurately.

The Philosophy of a Six-Year-Old and His Tiger

Watterson wasn't just drawing gags. He was reading Thoreau and Voltaire.

The name "Calvin" comes from the 16th-century theologian John Calvin (think: predestination). "Hobbes" comes from Thomas Hobbes, the 17th-century philosopher who thought human life was "nasty, brutish, and short."

That’s some heavy lifting for a funny page.

But it works because Watterson never talks down to his audience. He assumes you're smart enough to keep up. When Calvin rants about the "commercialization of the soul," he’s not just a kid being precocious; he’s Watterson’s mouthpiece for a world that was becoming increasingly obsessed with consumption. It’s ironic, really. Watterson refused to license his characters for plush toys or coffee mugs because he didn't want to cheapen the message. He left hundreds of millions of dollars on the table. In 2026, where every "influencer" is a walking billboard, that level of integrity feels like a myth from a lost civilization.

Navigating the Legacy of Today on Calvin and Hobbes

You’ve probably seen the bootleg stickers. You know the ones—Calvin leaning against a car or doing something crude. They’re everywhere. Watterson hates them. They are the only "merchandise" that really exists, and they represent the exact opposite of what the strip is about.

If you want the real experience of today on Calvin and Hobbes, you go to the source. GoComics still hosts the daily archives. It’s the digital version of the old-school funny pages.

The Art of the Rerun

The syndication cycle isn't random. It’s designed to mirror the seasons. If it’s January, Calvin is usually struggling with a sled or building a "calvinist" snowman (you know, the ones that are melting and screaming in agony). If it’s June, he’s dreading the end of school or getting eaten by "The Goober from the Deep" in the bathtub. This seasonal synchronization makes the strip feel "live" even though it’s been static for decades.

It creates a communal experience. When that specific strip about the "secret language" or the "G.R.O.S.S. club" pops up, thousands of people are seeing it at the same time. It’s a shared nostalgia that doesn't feel cheap.

Beyond the Daily Strip: The Complete Collection

While the daily hit is great for a quick hit of serotonin, the real depth comes from the collections. If you’ve ever lugged around the "Complete Calvin and Hobbes" three-volume treasury set, you know it’s heavy enough to use as a defensive weapon.

Reading them in bulk reveals things you miss in the daily scroll:

- The evolution of the line work. Early Hobbes looks a bit "stiffer." By the end, the lines are fluid, almost liquid.

- The recurring "Noodle Incident." We never find out what happened. We don't need to. Our imagination is funnier than any explanation Watterson could have provided.

- The heartbreakingly subtle relationship between Calvin’s parents. They are exhausted. They are frustrated. But they love each other, and they (mostly) love their chaotic son.

The "Watterson Style" of 2026

In an era of high-definition CGI and "perfect" digital art, Watterson’s hand-drawn ink lines feel incredibly human. You can see the slight wobbles. You can see the heavy brushstrokes in the Sunday watercolors. It’s a reminder that art is a physical act.

He didn't use a tablet. He used a Pen. Ink. Paper.

That tactile quality is why today on Calvin and Hobbes still grabs your eye on a screen. It looks different than the flat, vector-based illustrations that dominate modern web design. It has "soul," for lack of a better word. It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s occasionally very quiet.

Misconceptions About the End

People often think Watterson "retired" because he ran out of ideas. That’s not what happened. He was tired of the fight. He fought for the integrity of the art form for a decade. He fought for the right to not be a brand. He reached the end of what he wanted to say in that specific format, and he had the discipline to walk away while the work was still perfect.

He didn't want the strip to become a zombie, wandering the pages for 40 years past its expiration date (looking at you, Garfield). By quitting, he ensured that every time you look up today on Calvin and Hobbes, you’re seeing the "good stuff." There are no bad years. There are no "sell-out" arcs.

🔗 Read more: Tom Hanks and Wilson: Why a Bloody Volleyball Is Still Movie Magic

How to Keep the Magic Alive

If you’re someone who checks the strip daily, you’re already part of the club. But if you want to go deeper into why this stuff matters, there are a few things you can do that beat just scrolling through an image gallery.

- Check the Sunday Strips in High-Res: The detail in the "dinosaur" sequences or the Spaceman Spiff landscapes is insane. Look at the hatching and cross-hatching. It’s a masterclass in pen-and-ink technique.

- Read the "Tenth Anniversary Book": This is the holy grail for fans. Watterson provides commentary on individual strips and writes a long, biting essay about the state of the industry and his philosophy on art. It’s arguably more relevant now than when it was published.

- Introduce a Kid to the Books: This is the real litmus test. Give a seven-year-old a copy of The Revenge of the Baby-Sat and watch what happens. They don't need to know it's "classic" or "critically acclaimed." They just think it’s funny that a kid is trying to launch himself into space with a cardboard box.

The beauty of today on Calvin and Hobbes is that it doesn't require a subscription or a "pro" account. It’s just there. It’s a small, daily reminder that imagination is the only real escape we have from the "real world" of bills, commutes, and boring grown-up stuff.

Watterson’s legacy isn't just a comic strip. It’s a philosophy of life that prioritizes wonder over wealth and play over productivity. In a world that constantly asks us to be "on," Calvin reminds us it’s okay to just go outside and be a transmogrified owl for a while.

Actionable Next Steps

- Bookmark the official archive: Use GoComics or the official Calvin and Hobbes site to ensure you're supporting the legitimate syndication that honors Watterson’s original formatting.

- Audit your feed: If you find yourself doomscrolling, replace one "news" account with a classic comic feed. It changes your brain chemistry in a meaningful way.

- Pick up a physical book: There is something fundamentally different about reading these strips on paper versus a 6-inch glass screen. The scale of the Sunday strips deserves the extra real estate of a printed page.

- Research Watterson's later work: If you're a hardcore fan, look into his 2023 collaboration The Mysteries. It’s not Calvin, but it shows where his mind has gone in the years since he left the suburbs of Ohio behind.