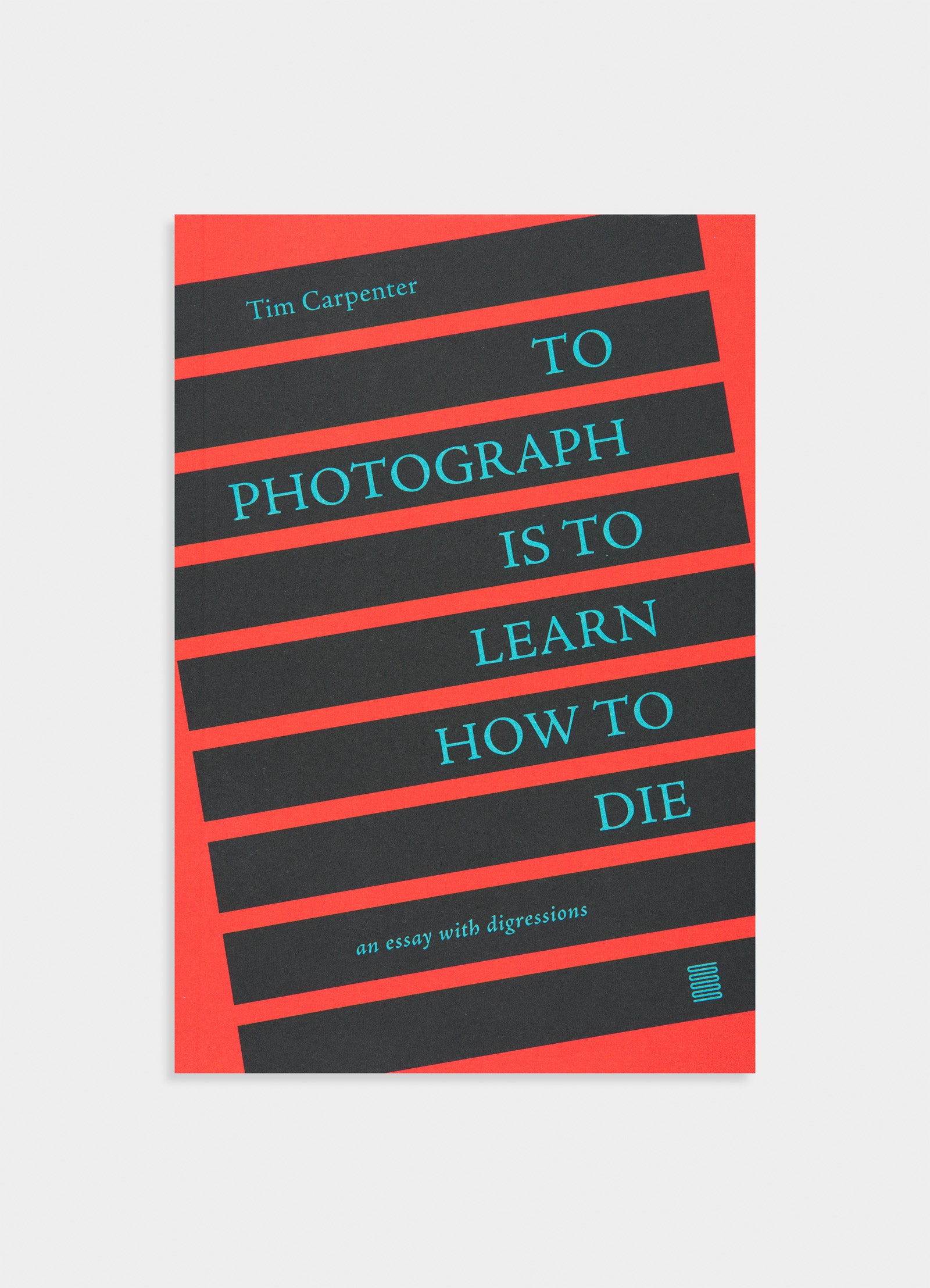

You’re standing there, phone out, trying to catch the sunset before it dips behind the skyline. It’s a nice moment. Maybe you’re with someone you love. But the second you click that shutter, something weird happens. You’ve basically killed the moment to save its ghost. Susan Sontag, the legendary critic who didn’t pull any punches, once suggested that to photograph is to learn how to die, and honestly, she wasn't just being dramatic for the sake of it.

Photography is a weird, beautiful, slightly morbid act of preservation.

Think about it. Every time you take a picture, you are acknowledging that the moment is already gone. It’s a tiny funeral for a fraction of a second. You’re freezing time, but time doesn't like being frozen. By the time the digital file hits your storage, the "you" in that photo doesn't exist anymore. Your cells have changed. Your mood has shifted. The light is different. Sontag’s 1977 masterpiece On Photography argues that taking a picture is a way of participating in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, and mutability. It’s a heavy thought for a Tuesday afternoon, but it’s the truth behind every selfie and street snap.

The Morbid Reality of the Shutter

We don’t usually think about death when we’re Instagramming our brunch. That would be a mood killer. But the core of the idea that to photograph is to learn how to die is rooted in the "memento mori" tradition. This is an old Latin phrase that basically means "remember you must die." In the 19th century, people took this literally with post-mortem photography, where they’d pose with dead relatives because it was the only way to keep their image. Today, we do the same thing, just with living subjects who are constantly aging.

Roland Barthes, another heavy hitter in photo theory, called the camera a "clock for seeing." In his book Camera Lucida, he talked about the punctum—that little sting of realization you get when looking at an old photo. It’s the "that-has-been" quality. You look at a photo of your grandfather as a kid and realize: he’s gone, or he’s going to be gone, and so am I. The camera proves that time is a one-way street.

It’s kinda like taxidermy for time.

Why We Can't Stop "Killing" the Moment

Sontag argued that photography is an elegiac art. That’s a fancy way of saying it’s a song for the dead. When we find something beautiful, we want to own it. We want to stop it. But you can’t own a sunset. You can only own a 2D representation of it. By choosing to look through a viewfinder or a screen instead of with your actual eyes, you’re distancing yourself from life. You’re stepping back. You’re becoming a collector of ghosts rather than a participant in the living world.

Is that bad? Not necessarily. But it’s definitely a choice.

💡 You might also like: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

It’s an act of aggression, in a way. Sontag actually pointed out how much of our photography language is borrowed from the world of weapons. We "load" a camera. We "aim." We "shoot." We "capture" a subject. We even talk about "framing" someone. This isn't accidental. It’s a way of exerting power over a world that is constantly slipping through our fingers. By "shooting" the world, we feel like we’ve mastered it, even though we’re just as mortal as the things we’re photographing.

The Digital Paradox: More Photos, Less Memory?

We take more photos now than at any point in human history. Billions every day. If to photograph is to learn how to die, then we are currently obsessed with the process of dying. We are documenting our lives so intensely that we barely have time to live them.

There’s this thing called the "photo-taking impairment effect." Researchers like Linda Henkel have found that when people take photos of objects in a museum, they actually remember fewer details about the objects themselves compared to people who just looked at them. The brain essentially says, "Oh, the phone’s got this, I don't need to pay attention." We are offloading our memories to a cloud. We are creating a massive digital cemetery of moments we didn't actually experience because we were too busy making sure the focus was sharp.

Sontag, Barthes, and the Weight of the Image

To really get why people say to photograph is to learn how to die, you have to look at the work of photographers who leaned into the darkness.

- Diane Arbus: She photographed people on the fringes of society. Her work feels like a confrontation with the "otherness" of human life. She once said, "A photograph is a secret about a secret." She knew that the image wasn't the truth; it was a mask.

- Nan Goldin: Her Ballad of Sexual Dependency is basically a long-form obituary for a lifestyle and a group of friends, many of whom were lost to the AIDS crisis. The photos are vibrant and alive, which makes the reality of their subjects' deaths even more crushing.

- Robert Frank: In The Americans, he stripped away the shiny veneer of 1950s optimism to show the loneliness and the "dying" spirit of a nation.

These photographers understood that a camera isn't just a tool for making pretty pictures. It’s an intervention. It interrupts the flow of life to say, "Look at this, because it won’t be here in a second."

The Psychological Toll of the "Perfect" Image

The pressure to document everything creates a weird kind of anxiety. We’ve all felt it. That itch to grab the phone when something cool happens. If you don't photograph it, did it even happen? This is the modern version of Sontag’s concern. We’ve become addicted to the image of our lives rather than the quality of them.

We are constantly editing our own histories. We delete the "bad" photos—the ones where we look tired, or old, or sad. But those are the photos that actually show our mortality. By only keeping the "perfect" shots, we’re creating a lie. We’re trying to pretend we aren't aging, aren't changing, and aren't dying. But the very act of taking the photo proves that we are.

📖 Related: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

It’s honestly a bit of a loop. You take a photo to stop time because you’re afraid of time passing. But the photo itself becomes a marker of how much time has passed. Every time you look at an old photo of yourself, you’re reminded of what you’ve lost.

Practical Insights: How to Use Your Camera Without Losing Your Soul

So, if to photograph is to learn how to die, should we just throw our cameras in the river? Probably not. But we can change how we use them. Photography can be a way of paying deeper attention to the world, rather than just "capturing" it.

Instead of mindlessly snapping, try these approaches to make your photography a living act rather than a funeral rite:

Limit your shots. Back in the film days, you had 24 or 36 exposures. You had to make them count. Try going out for a day and only allowing yourself 10 photos. You’ll find yourself looking much more closely at the world. You’ll wait for the right light. You’ll engage with the scene. You’ll be alive in the moment because you can’t afford to waste a shot.

The "Eyes First" Rule. Give yourself thirty seconds to just look at something before you reach for your camera. Smell the air. Listen to the sounds. Feel the temperature. If you still want to take the photo after that, go for it. But make sure the memory is in your brain before it’s on your SD card.

Photograph the "Ugly" stuff. Don't just chase the sunsets and the smiles. Photograph the mess. The dirty dishes. The tired face of a friend. The cracked pavement. These are the things that actually anchor us in reality. They acknowledge the "mutability" that Sontag talked about. They embrace the fact that things fall apart.

Print your photos. There is something fundamentally different about a physical print versus a digital file. A print ages. It fades. It gets creases. It lives and dies just like we do. A digital file is an immortal, sterile string of ones and zeros. By printing your photos, you’re letting them join you in the physical world.

👉 See also: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

Why This Still Matters in 2026

We live in an era of AI-generated images and deepfakes. The "truth" of a photograph is under fire. But the feeling of a photograph remains. We still use photos to grieve. We still use them to remember.

The idea that to photograph is to learn how to die isn't meant to be depressing. It’s meant to be a wake-up call. It’s a reminder that life is fleeting and that no amount of megapixels can save us from the passage of time. When we accept that every photo is a small farewell, we actually start to value the moments more.

We realize that the sunset is beautiful precisely because it’s ending. The person across from us is precious because they won't be there forever.

Photography, at its best, is an act of love for a world that is constantly disappearing. It’s a way of saying, "I saw this. I was here. This mattered." Even if the moment is dead, the fact that it happened remains. And that’s enough.

Your Next Steps for Mindful Documentation

If you want to move beyond the "death" of the moment and into a more conscious way of seeing, start by auditing your photo library. Look at the last hundred photos you took. How many of them do you actually remember taking? How many of them evoke a physical sensation or a specific memory beyond just what the image shows?

Next time you’re out, try the One-Photo-Only challenge for an entire event. Whether it’s a wedding, a concert, or a hike, allow yourself exactly one frame. Spend the rest of the time being entirely present. You might find that the memory of the event is much sharper when you aren't viewing it through a screen.

Finally, read Sontag’s On Photography. It’s not an easy read, and she can be a bit cynical, but it will fundamentally change the way you look at your phone. It’ll make you realize that while a camera can "kill" a moment, it can also be the tool that finally teaches you how to truly see.

Stop "shooting" and start seeing. The world is moving fast; don't miss it while you're trying to save it.