It’s actually kinda wild when you think about it. Most movies from the early sixties feel like they belong in a museum, trapped in amber with stiff acting and sets that look like cardboard. But then you sit down and watch the To Kill a Mockingbird movie, and within five minutes, you’re lost in the heat of a Maycomb summer. You can practically hear the cicadas. It’s not just "good for its time." It’s a powerhouse.

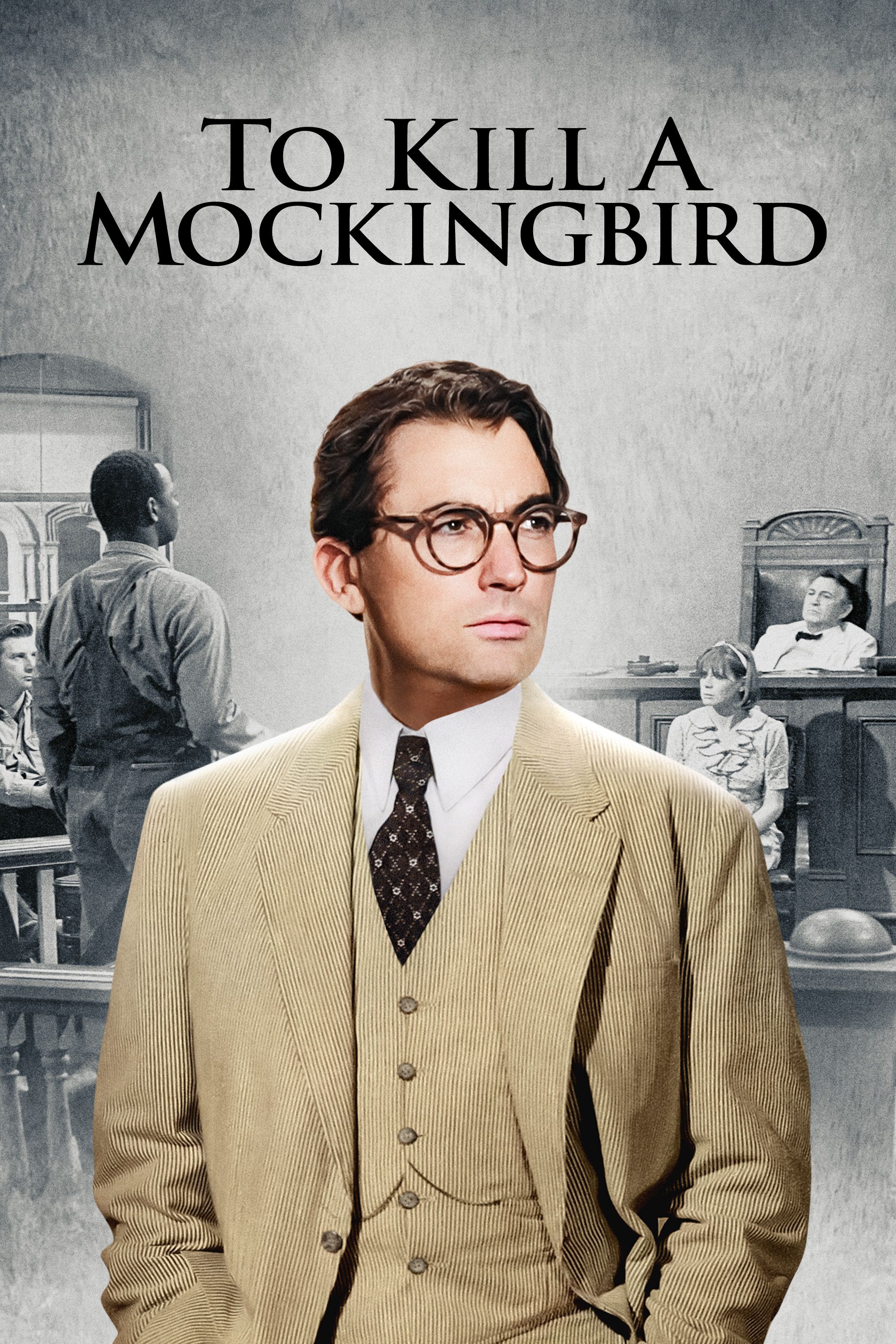

Gregory Peck didn't just play Atticus Finch; he became the blueprint for what we want a father to be. He’s steady. He’s calm. He doesn't raise his voice, yet everyone listens. Honestly, the way the film captures that specific childhood feeling of realizing your parents are actual humans with their own struggles—it’s just perfect.

But there’s a lot more to the story than just a lawyer in a suit.

The Struggle to Get the To Kill a Mockingbird Movie Made

Hollywood almost missed out on this one. When Harper Lee’s book exploded in 1960, studios were actually nervous. They saw a story about racial injustice, the Deep South, and a trial that doesn't exactly have a "happy" ending in the traditional sense. It wasn't seen as a blockbuster.

Producer Alan J. Pakula and director Robert Mulligan were the ones who saw the magic. They knew they didn't want a "message movie" that hit people over the head. They wanted a movie about childhood. That’s the secret sauce. By framing the heavy themes through the eyes of Scout and Jem, the medicine goes down differently.

Universal Pictures eventually bit, but they were skeptical. They had a budget of about $2 million, which wasn't huge even then. They filmed mostly on a backlot at Universal because Maycomb, Alabama, had changed too much by the sixties to look "authentic" to the 1930s. If you watch closely, you can see how they built that neighborhood to feel claustrophobic yet magical. It worked.

Gregory Peck and the Ghost of Atticus Finch

It's impossible to talk about the To Kill a Mockingbird movie without mentioning Gregory Peck. He won the Oscar for Best Actor, and rightfully so. But did you know he wasn't the first choice? Rock Hudson was actually considered. Imagine that. It would have been a completely different film—probably a lot more "Hollywood" and a lot less soulful.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Peck took the role so seriously that he traveled to Monroeville, Alabama, to meet Harper Lee’s father, Amasa Coleman Lee. Amasa was the real-life inspiration for Atticus. Harper Lee famously said that when she saw Peck in the suit on set, she started to cry because he looked so much like her father, right down to the way he carried his watch.

Peck kept that watch for the rest of his life.

The courtroom scene is where the movie cements its legacy. It’s a nine-minute closing argument. Nine minutes! In modern filmmaking, you’d have fifty cuts and a swelling orchestra. Mulligan kept the camera mostly steady on Peck. He wanted the audience to feel like they were sitting in that "colored balcony," watching a man fight a losing battle with nothing but his integrity. Peck actually did the entire nine-minute speech in one single take. When he finished, the crew didn't even want to clap—they were just stunned into silence.

The Kids Who Never Acted Before

One of the biggest risks the production took was casting Mary Badham and Phillip Alford. Neither had professional acting experience.

Mary Badham was nine. She was just a kid from Birmingham. Because she wasn't a "child actor," she didn't have those annoying, rehearsed habits. Her Scout is messy, loud, and incredibly observant. She and Gregory Peck formed a real bond on set that lasted until he died in 2003. He always called her "Scout."

Then there's the Boo Radley of it all.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

Most people forget that the To Kill a Mockingbird movie was the film debut of Robert Duvall. He doesn't say a single word. Not one. He spent six weeks staying out of the sun so he would look ghostly pale. When he finally steps out from behind that door at the end, it’s one of the most poignant moments in cinema history. He’s not a monster. He’s just a shy, broken man.

Why Some Parts of the Movie are Controversial Today

We have to be real here. Looking at the film in 2026, people have different opinions than they did in 1962.

A major critique is the "White Savior" trope. The movie focuses heavily on Atticus’s moral journey. While Brock Peters gives a heartbreaking, visceral performance as Tom Robinson, the story doesn't spend much time on Tom's life outside of his victimization. The Black community in Maycomb is portrayed as noble and stoic, but they are largely background characters in their own tragedy.

Some film historians, like Donald Bogle, have pointed out that while the film was progressive for its era, it still prioritizes the white perspective on racism. It’s a fair point. The movie is a product of its time. It was released during the height of the Civil Rights Movement—just months before the March on Washington—and for many white Americans, it was their first real confrontation with the systemic unfairness of the legal system.

The Visual Style: Not Just a Standard Drama

If you watch the movie again, pay attention to the shadows. It’s filmed in black and white, even though color was widely available by 1962. This was a deliberate choice.

The cinematographer, Russell Harlan, used high-contrast lighting to create a "Southern Gothic" vibe. The Radley house looks like it’s out of a horror movie. The night scenes with the fire and the mad dog are genuinely tense. It feels more like a memory or a dream than a documentary.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

The score by Elmer Bernstein is another masterpiece. Instead of a massive 80-piece orchestra, he used a small ensemble. It starts with a simple piano tinkling, like a child playing. It’s intimate. It doesn't tell you how to feel; it just sits there with you in the humid Alabama air.

Surprising Facts You Probably Didn't Know

There are a few things that usually fly under the radar:

- The Set Was a Maze: They actually bought real houses from a local area in Los Angeles that was being cleared for a freeway and moved them onto the Universal lot to create the street.

- The Dress: Mary Badham hated the ham costume she had to wear for the pageant. It was made of real wire and burlap, and she couldn't sit down in it.

- The Script: Horton Foote wrote the screenplay. He was so faithful to the book that Harper Lee called it "one of the best translations of a book to film ever made."

- The Oscar Race: It was up against Lawrence of Arabia for Best Picture. It lost, but many argue that Mockingbird has had a more direct impact on American culture and law.

How to Watch the Movie with Fresh Eyes

If you’re planning a rewatch or seeing it for the first time, don't just look at the trial. Look at the edges of the frame.

Notice how often the camera is at the height of a child. We see the world from Scout's eye level. We see the knees of the adults, the bottom of the porch swings, the terrifying height of the Radley porch. This perspective is what makes the ending—where Scout finally stands on the Radley porch and sees the neighborhood from Boo's perspective—so powerful. It’s a literal shift in viewpoint.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Students

If you want to go deeper into the To Kill a Mockingbird movie and its legacy, here is what you should actually do:

- Watch the "Fearful Symmetry" Documentary: Most Blu-ray editions of the film include this. It’s an incredibly detailed look at the production, featuring interviews with the cast and the people of Monroeville. It debunks a lot of the myths about the filming process.

- Compare the Trial to Real History: Research the Scottsboro Boys trial. This was the real-life 1931 case that heavily influenced Harper Lee. Seeing the parallels between the real trial and the fictional one makes the movie’s stakes feel much more grounded.

- Listen to the Score Individually: Find Elmer Bernstein’s soundtrack on a streaming service. Listen to how it shifts from the innocence of the "Main Title" to the tension of "The Mad Dog." It’s a masterclass in minimalist film scoring.

- Visit the Monroe County Heritage Museum: If you're ever in Alabama, they have a permanent exhibit. You can sit in the courtroom that was used as the model for the movie’s set. They even do a play every year using local residents.

- Check Out "Go Set a Watchman": If you want a more cynical, complicated look at Atticus Finch, read Lee's controversial sequel/first draft. It makes you appreciate the "heroic" version in the 1962 film even more because it shows how hard it is to maintain that kind of moral clarity.

The To Kill a Mockingbird movie isn't just a "school requirement." It’s a snapshot of a turning point in American history. It deals with empathy—not the cheap kind, but the hard kind. The kind where you have to stand in someone else's shoes and "walk around in them." That’s a lesson that doesn't age, no matter how many years pass.