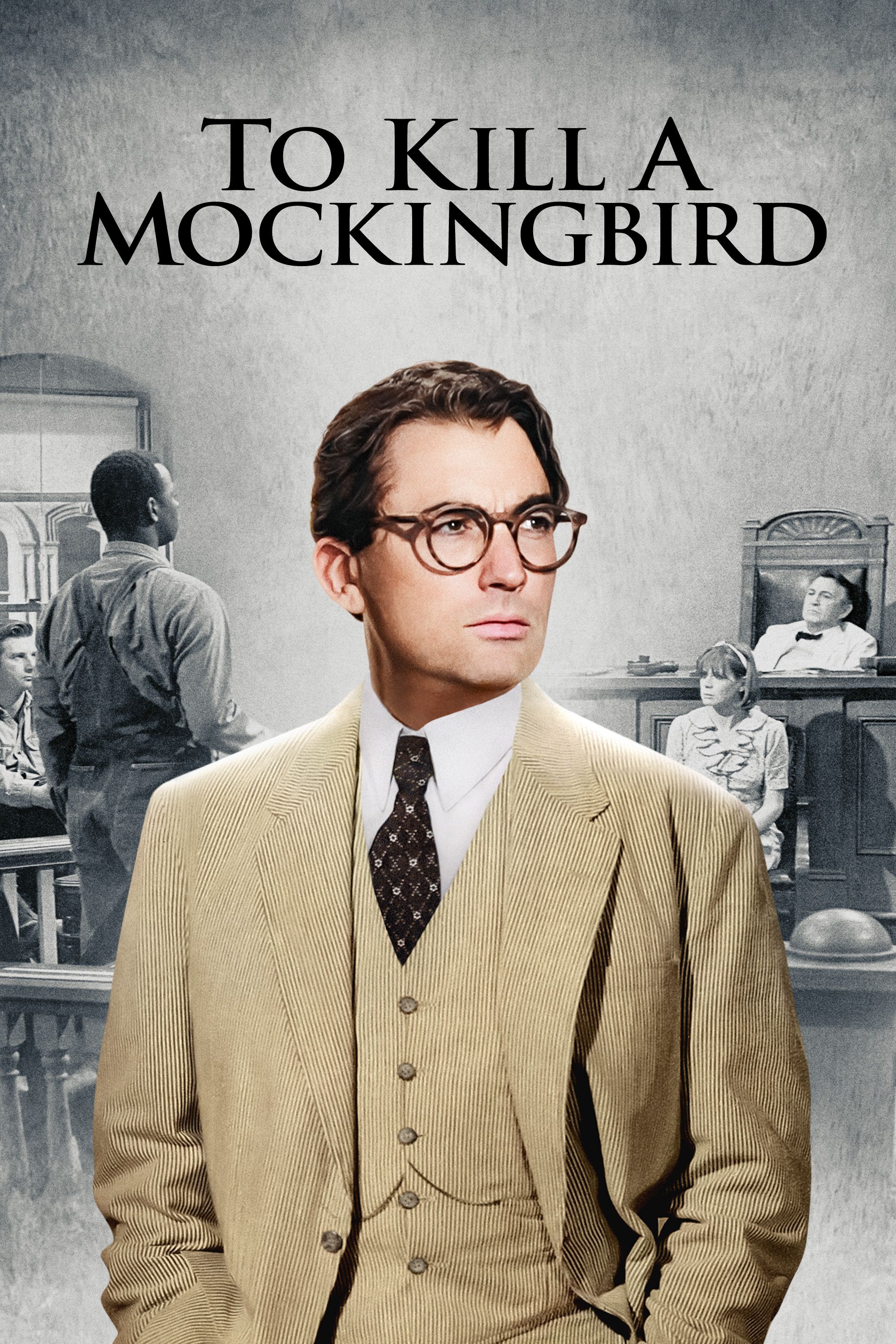

Most people remember the courtroom. They remember Gregory Peck—or maybe just the mental image of Atticus Finch—standing tall in a humid Alabama courthouse, defending Tom Robinson. Because of that, if you ask the average person about the To Kill a Mockingbird genre, they’ll probably tell you it’s a legal thriller or a "courtroom drama."

They aren't exactly wrong. But they are missing the bigger picture.

Harper Lee didn't just write a book about a trial. Honestly, the trial doesn't even start until you're halfway through the story. What she actually built was a complex, messy, and deeply emotional "Southern Gothic" coming-of-age tale. It’s a book that lives in the humid air of the American South, seen through the eyes of a child who is slowly realizing that her neighbors aren't who she thought they were.

The Coming-of-Age Core (The Bildungsroman)

At its heart, the primary To Kill a Mockingbird genre is the Bildungsroman. That’s a fancy literary term for a coming-of-age story. We see everything through Scout Finch. She starts the book as a messy-haired tomboy who thinks the biggest threat in the world is the "haint" living down the street. By the end? She's seen systemic racism, attempted murder, and the death of innocence.

It's a transformation.

Think about how Scout, Jem, and Dill change. In the beginning, their world is tiny. It's just the boundaries of their neighborhood in Maycomb. Their "villains" are Boo Radley—a man they’ve never seen but have turned into a monster in their heads. As the pages turn, the genre shifts. The imaginary monsters are replaced by real ones: Bob Ewell, the town’s bigotry, and the crushing weight of an unfair legal system.

The growth isn't just about getting older. It's about the loss of that childhood safety net. When Atticus tells Scout that you never really understand a person until you "climb into his skin and walk around in it," he isn't just giving fatherly advice. He’s defining the thesis of the entire Bildungsroman arc.

👉 See also: Nothing to Lose: Why the Martin Lawrence and Tim Robbins Movie is Still a 90s Classic

Southern Gothic: More Than Just Spooky Houses

You can’t talk about the To Kill a Mockingbird genre without mentioning Southern Gothic. This isn't horror, but it feels like it sometimes. Southern Gothic literature uses macabre themes and eccentric characters to highlight the decay of the post-Civil War South.

Maycomb is a character itself. It’s tired. It’s "suffocatingly hot."

The town is full of people who are stuck in the past, clinging to old social hierarchies that are rotting from the inside out. Boo Radley’s house is the ultimate Southern Gothic trope—the decaying mansion with a mystery inside. But the "monsters" in this genre aren't ghosts. They are the social norms that keep people like Mayella Ewell trapped in poverty and people like Tom Robinson trapped in a cell.

Truman Capote, a close friend of Harper Lee (and the inspiration for the character Dill), was a master of this style. You can see his influence in the way Lee describes the Radley Place. The "rain-spotted tin roof" and the "shingles that reached over the eaves of the veranda" create a sense of dread that persists even when the sun is shining. It’s about the darkness lurking under the surface of polite Southern society.

The Courtroom Drama Misconception

Everyone focuses on the trial. It makes sense. It’s the most intense part of the book. It’s where the moral stakes are highest. Because of this, many libraries and bookstores categorize the To Kill a Mockingbird genre as legal fiction.

But here’s the thing: Atticus loses.

✨ Don't miss: How Old Is Paul Heyman? The Real Story of Wrestling’s Greatest Mind

In a traditional legal thriller—think John Grisham—the hero usually finds the "smoking gun" or uses a brilliant legal loophole to save the day. To Kill a Mockingbird does the opposite. Atticus proves, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that Tom Robinson is innocent. He does everything right. And it still doesn't matter. The jury convicts Tom anyway because of the color of his skin.

This subversion of the legal drama is what makes the book a masterpiece. It uses the structure of a trial to expose the fact that the law is only as good as the people who sit in the jury box. If the people are broken, the law is broken. By using the legal genre as a vehicle, Lee shows the reader that "justice" is often just a word people use to feel better about themselves.

Historical Fiction or Social Commentary?

Published in 1960, right in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement, the book is set in the 1930s during the Great Depression. This puts it firmly in the historical fiction category. However, it functions much more like social commentary.

Lee was writing about the 30s to talk about the 60s.

The Great Depression setting provides a backdrop of desperation. When people are hungry and poor, they look for someone to look down on. The "Ewells" of the world need the "Tom Robinsons" to be beneath them so they don't feel like they’re at the very bottom of the pile. This sociological layer adds a weight to the To Kill a Mockingbird genre that simple historical fiction often lacks. It’s not just a "period piece." It’s a mirror.

Why the Genre Blend Still Works Today

The reason this book is still taught in almost every high school in America is that it refuses to stay in one lane. If it were just a coming-of-age story, it might feel too light. If it were just a legal drama, it might feel too dry.

🔗 Read more: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

Instead, it’s a hybrid.

It’s a story about a girl learning to read the world, a father trying to maintain his integrity in a failing system, and a town dealing with its own internal rot. It captures the "mockingbird" metaphor perfectly—the idea of innocence being destroyed by the very things meant to protect it.

Identifying the Genre Markers

- Perspective: First-person child narrator (Standard for Bildungsroman).

- Tone: Melancholic, nostalgic, yet sharp and critical.

- Setting: Small-town Alabama (Crucial for Southern Gothic).

- Plot Structure: Dual-narrative (Part 1 focuses on the children and Boo; Part 2 focuses on the trial).

Final Insights for the Modern Reader

If you're looking to truly understand the To Kill a Mockingbird genre, don't just look at the plot. Look at the atmosphere. The book is a protest novel wrapped in a childhood memoir. It uses the "safe" genre of a children’s story to deliver a brutal critique of American prejudice.

To get the most out of your next re-read or study session, try these steps:

- Compare the two halves: Notice how the "spooky" elements of Part 1 (Boo Radley) mirror the "real" horrors of Part 2 (The Trial).

- Watch for the Gothic elements: Pay attention to how Lee describes the physical decay of Maycomb. It usually signals moral decay.

- Analyze the "Mockingbird" characters: Identify who in the story represents innocence. It isn't just Tom Robinson; it’s also Boo Radley and, eventually, the children themselves.

- Look at the dates: Research the 1955 trial of Emmett Till. Harper Lee was writing this book while that real-life horror was fresh in the American psyche. It changed the way she approached the courtroom scenes.

By seeing the book as a blend of Southern Gothic, Bildungsroman, and social protest, you see the full scope of Harper Lee’s genius. It’s not just a classic; it’s a complex piece of machinery designed to make you uncomfortable with the status quo.

Next time someone asks you about the genre, tell them it's a "Gothic Bildungsroman with a legal spine." You'll sound like an expert, and more importantly, you'll be right.