If you walked into a bookstore in 1960 and picked up Harper Lee’s debut, you might have thought you were just getting a dusty story about a small-town lawyer. You’d be wrong. Determining the To Kill a Mockingbird genre isn't as straightforward as ticking a single box on a library card. It’s a shapeshifter. It’s a Southern Gothic ghost story that somehow morphs into a gritty legal thriller before finally settling into a heartbreaking "coming-of-age" tale.

Most people just call it a "classic" and move on. But that’s lazy.

To really get why this book still hits people in the gut sixty years later, you have to look at how Lee blended genres that usually don't play nice together. She took the eerie, decaying vibes of the American South and smashed them against the cold, hard logic of a courtroom. It shouldn't work. It does.

The Bildungsroman: Growing Up Is Violent

At its heart, the primary To Kill a Mockingbird genre is the Bildungsroman. That’s a fancy German word for a "coming-of-age" story, but it’s more specific than that. It tracks the moral and psychological growth of the protagonist. In this case, that’s Scout Finch.

Scout starts the book as a kid who thinks the biggest threat in the world is a creepy neighbor who doesn't come outside. By the end, she’s seen a man lynched in spirit and another murdered in reality. That transition from innocence to experience is the engine of the entire plot.

Think about the way Lee handles the passage of time. It’s slow. It’s languid. It feels like a humid Alabama summer. But then, suddenly, things get sharp. When Atticus shoots the rabid dog, Tim Johnson, the genre shifts for a second. It becomes a loss-of-innocence moment. Scout and Jem realize their father isn't just a man who reads; he’s a man who can deal death when necessary. That’s a classic trope of the Bildungsroman—the shattering of the childhood image of a parent.

Southern Gothic: More Than Just Old Houses

You can’t talk about the To Kill a Mockingbird genre without mentioning Southern Gothic. This isn't just "horror-lite." It’s a specific vibe that uses Macabre or grotesque themes to comment on social issues.

The Radley Place is the quintessential Gothic setting. It’s decaying. It’s shrouded in mystery. Boo Radley himself is treated like a local urban legend—a "malevolent phantom." Lee uses these Gothic elements to mirror the actual "monsters" of Maycomb: racism and prejudice.

- The Boo Radley Subplot: This starts as a ghost story.

- The Ewell Family: They represent the "grotesque" in Southern Gothic literature—poverty-stricken, bitter, and dangerous.

- The Environment: The heat, the dirt, the slow-moving pace of a town "with nowhere to go."

Scholars like Eric J. Sundquist have often noted how Southern Gothic literature uses the "haunted" past of the South to talk about the things people are too scared to say out loud. Maycomb is haunted. Not by ghosts, but by the history of slavery and the Jim Crow laws that were very much alive when Lee was writing.

The Courtroom Drama: The Pivot Point

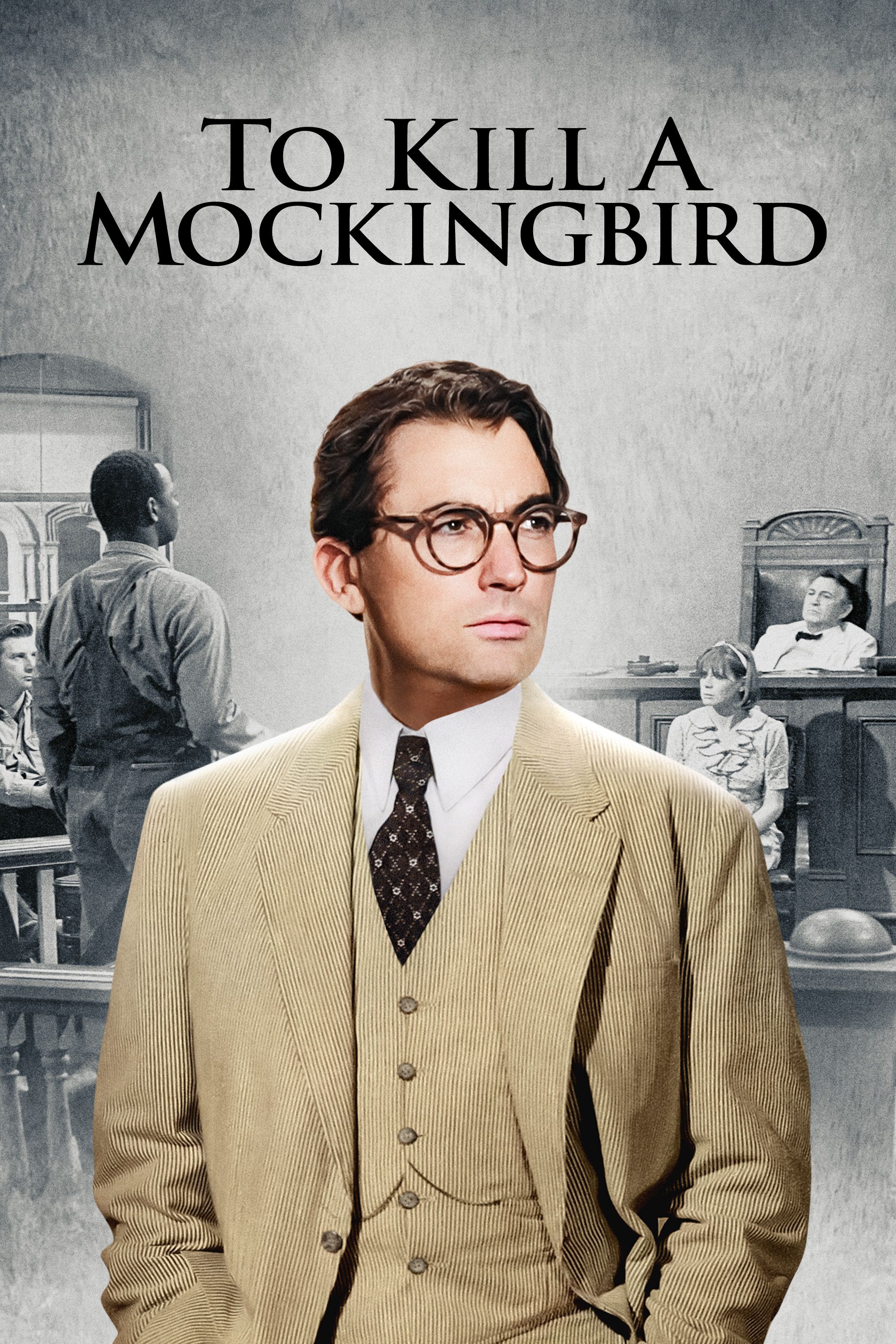

Halfway through, the book takes a hard left turn. Suddenly, we are in a legal thriller. This is the To Kill a Mockingbird genre that most people remember from the 1962 film starring Gregory Peck.

The trial of Tom Robinson is a masterclass in legal tension. But here’s the thing: unlike a John Grisham novel where the "good guy" wins through a last-minute piece of evidence, Lee uses the courtroom to show the failure of the law. It’s a subversion of the genre. Usually, in a legal drama, the truth sets you free. In Maycomb, the truth is irrelevant compared to the social hierarchy.

Atticus Finch’s closing argument is often cited by real-world lawyers as a pinnacle of rhetorical excellence. He appeals to the "God-fearing white men" of the jury, trying to use their own logic against them. It’s high drama. It’s tense. It’s also, fundamentally, a tragedy.

Social Realism and the Mirror to 1930s Alabama

Is it a historical novel? Technically, yes. Lee wrote it in the late 1950s, but it’s set in the 1930s. This creates a weird double-layer of perspective. She’s looking back at the Great Depression through the lens of the early Civil Rights Movement.

This brings in the genre of Social Realism.

Social realism focuses on the "ugly" parts of life to provoke change. Lee doesn't sugarcoat the poverty of the Cunninghams or the sheer malice of Bob Ewell. She describes the "tired old town" with a bluntness that felt revolutionary at the time. By depicting the racial caste system of Maycomb so accurately, she wasn't just telling a story; she was filing a report on the state of the American soul.

Why the Genre Label Matters for Modern Readers

People often argue about whether To Kill a Mockingbird is "Young Adult" fiction. Honestly? It’s complicated. Because it’s told through the eyes of a child, schools often shove it into the YA category. But the themes are so heavy—rape, systemic injustice, the death of the "mockingbird"—that it transcends that label.

If you approach it only as a "school book," you miss the nuance. You miss the fact that it's a deeply funny book in parts. Scout’s narration is witty and cynical. That humor is a key part of the "Regionalist" genre—capturing the specific voice and quirks of a particular place.

🔗 Read more: Pimp Lyrics by 50 Cent: What Most People Get Wrong

The Problem with "White Savior" Narratives

In the last decade, critics have started looking at the To Kill a Mockingbird genre through a more critical lens. Some argue it fits into the "White Savior" trope. This is the idea that the story focuses more on the moral growth of the white characters (Atticus and Scout) than on the actual victim (Tom Robinson).

While Atticus is a hero, he is also a man of his time. He believes the system can work, even when it’s clearly broken. Recognizing this doesn't "cancel" the book; it just adds a layer of complexity to the genre analysis. It’s a 1960s perspective on a 1930s problem.

Actionable Insights for Reading or Teaching the Novel

If you are diving back into this book or helping someone else understand it, don't just look for "themes." Look for how the genres clash.

- Identify the "Gothic" moments: Notice how Lee uses the scary house at the end of the street to represent the town's fear of the unknown.

- Track Scout's Voice: Watch how her vocabulary and observations change. Does she sound like a child or an adult reflecting on her childhood? This is the "Dual Perspective" often found in Bildungsromans.

- Analyze the Courtroom Failures: Don't just focus on Atticus's speech. Look at the jury. Why does the genre of "Legal Thriller" fail to provide a "Happy Ending"?

- Compare it to the Sequel: If you really want to see how genre shifts, look at Go Set a Watchman. It’s a much more cynical, purely "Adult Fiction" take on the same characters.

Understanding the To Kill a Mockingbird genre isn't about being a literary snob. It’s about understanding how Harper Lee used every tool in the writer's toolbox to make a point. She used ghosts to talk about race. She used a child's eyes to talk about adult corruption. She used a courtroom to show that the law isn't always just.

It’s not just a book. It’s a hybrid. And that’s exactly why it’s still on your shelf.

To explore this further, your next step should be to compare the 1930s setting of the novel with the actual historical events of the Scottsboro Boys trial, which heavily influenced the legal aspects of the plot. You can also read Harper Lee’s rare interviews to see how she felt about the "Southern writer" label often forced upon her by the New York literary establishment.