Water is heavy. That seems like a simple, almost stupid observation, but it’s the primary reason a Titanic sinking simulation is so difficult to get right. When you’re dealing with 52,000 tons of steel meeting the freezing Atlantic, the math gets messy. Fast. Honestly, most people think they know how the ship went down because they watched James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster. And while that movie was a masterpiece of practical effects and early CGI, our understanding of the fluid dynamics and structural failure has shifted significantly since then.

The ship didn’t just tip up and slide under. It groaned. It twisted.

The Evolution of the Titanic Sinking Simulation

Early attempts to recreate the disaster were, frankly, pretty crude. We’re talking about basic wireframe models that didn't account for the weight of the engines or the specific way the bulkheads failed. But things changed in the mid-2000s. Engineers began using Finite Element Analysis (FEA). This is the same stuff Boeing uses to make sure planes don't fall apart in mid-air.

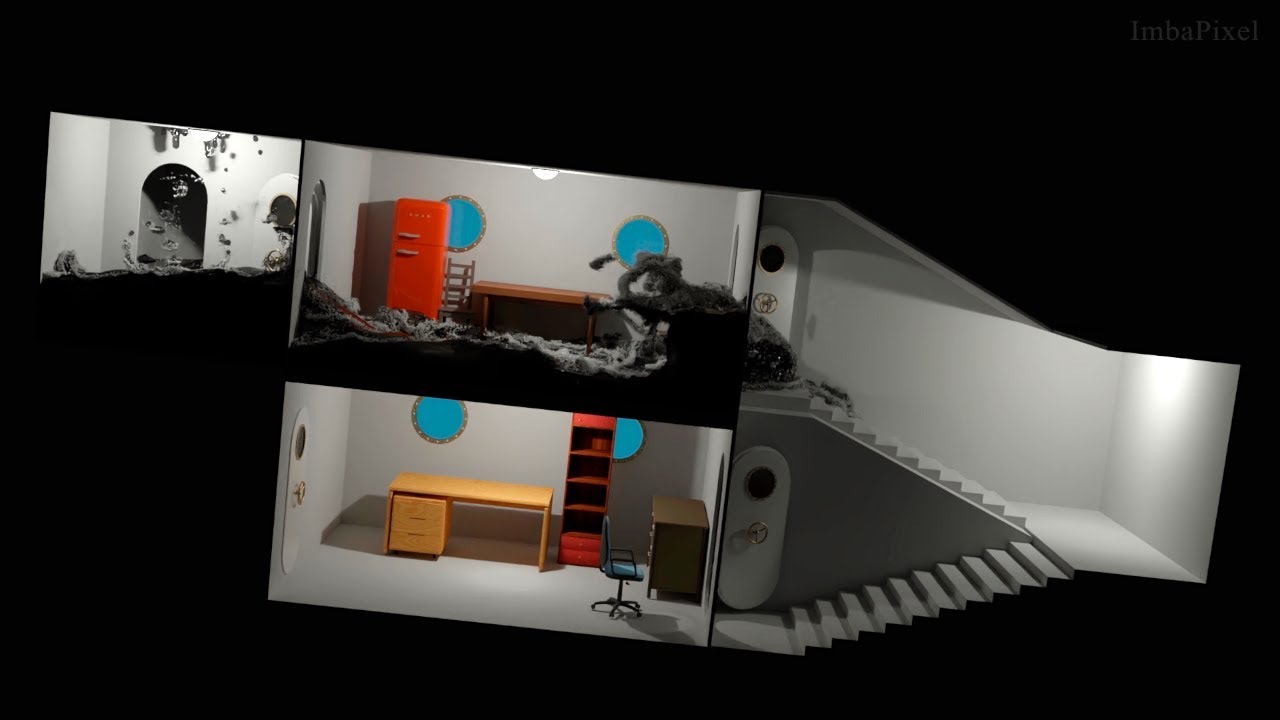

By 2012, for the centenary, we started seeing real-time simulations that lasted the full two hours and forty minutes. One of the most famous projects, Titanic: Honor and Glory, basically set the gold standard. They didn't just animate a ship; they built a digital forensic reconstruction. You see the water creeping up the Grand Staircase not as a scripted event, but as a result of digital "water" interacting with a 3D environment. It’s haunting.

📖 Related: Astronaut Stranded in Space: What Really Happened to Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore

It’s not just for gamers or history buffs, though.

Scientists use these models to understand "ship wreck mechanics." When the Titanic broke in two, it wasn't a clean snap. The double bottom—the very floor of the ship—acted like a hinge. It pulled the bow and stern back together briefly before the final plunge. Modern simulations prove that the stern likely stood much more vertical than we originally thought, perhaps reaching an angle of 30 to 45 degrees before the structural failure became catastrophic.

The Physics of the Breakup

Why did it break? Most ships don't.

Usually, a ship will just founder and sink in one piece. But the Titanic was a different beast. Because the bow was filled with water and the stern was still full of air, the middle of the ship was under an impossible amount of stress. It’s called "hogging." Imagine holding a long piece of dry spaghetti and pushing down on the ends while the middle stays unsupported. It’s going to snap.

- The bow pulls down as water fills the forward five compartments.

- The stern rises, exposing the propellers (the "screws").

- The keel—the backbone of the ship—reaches its yield point.

- Steel, even the high-quality stuff Harland & Wolff used, becomes brittle in 28-degree water.

The simulation reveals that the breakup likely started from the top down, through the superstructure, rather than from the bottom up. This is a nuance that early researchers like Robert Ballard debated for years. Now, with high-fidelity modeling, we can actually see the "banana effect" where the ship's frame deforms before the final separation.

Why Real-Time Matters

Most people have a short attention span. I get it. But watching a Titanic sinking simulation in real-time—all 160 minutes of it—changes your perspective on the tragedy. It wasn't a quick event. It was a slow, agonizing realization.

There were long periods where the ship seemed stable. Imagine standing on the deck at 12:30 AM. The lights are on. The band is playing. The ship has a slight list, but it feels solid. Then, suddenly, the "plunge" starts. This is where the simulation gets intense. Once the water reaches the Bridge, the rate of sinking accelerates exponentially. This is due to the "spillover" effect. Titanic was designed with sixteen watertight compartments, but the walls (bulkheads) didn't go all the way to the top. As one filled, it spilled into the next, like an ice cube tray tilted under a faucet.

The Role of the "V-Break" Theory

For a long time, the "Big Piece"—a massive section of the hull recovered from the debris field—confused experts.

Newer simulations suggest a "V-break." In this scenario, the ship broke, but the sections remained attached by the double bottom. As the bow pulled the stern down, they actually smashed into each other like a pair of closing jaws. This explains why there is so much mangled steel at the break site that looks like it was crushed rather than torn.

Simulation tech also accounts for the "internal" physics. We aren't just looking at the hull. We're looking at the air pressure. As the ship sank, air trapped in the stern had nowhere to go. It compressed until it literally blew the decks apart from the inside out. This is why the stern section of the wreck is such a mess compared to the relatively intact bow. It basically exploded under the pressure of the ocean.

The Human Element in Digital Recreations

You might wonder why we keep doing this. Is it just morbid curiosity?

Sorta. But it’s also about accuracy and respect.

📖 Related: How to Finally Tell Your Devices to Quit Spying on Me

When researchers like Parks Stephenson or Ken Marschall look at these simulations, they are looking for clues that match the survivor testimony. For decades, some survivors claimed the ship broke in two. Others swore it sank intact. The "official" British and American inquiries in 1912 concluded it sank in one piece. They basically called the survivors liars.

It wasn't until 1985, when Ballard found the wreck, that the "breakers" were vindicated. Today’s simulations show exactly why there was confusion. In the dark, with only the ship's lights (which stayed on until the very end), the breakup happened at or just below the waterline. To someone in a lifeboat a mile away, it might have looked like the ship just slipped under.

How to Experience a Modern Simulation

If you want to see this for yourself, you don't need a supercomputer.

- YouTube Creators: Channels like Part Time Explorer or the Titanic: Honor and Glory team post updated 4K simulations regularly. They update these whenever new deck plans or wreck footage emerge.

- VR Experiences: There are several VR titles that allow you to stand on the deck as the water rises. It’s a terrifying way to understand the scale of the ship.

- Scientific Papers: Organizations like NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) have released white papers on the steel composition and fracture mechanics of the hull.

The level of detail is insane now. You can see the specific way the lifeboats were lowered—how they scraped against the side of the hull because the ship was listing so badly. You can see the water rushing through the portholes that were left open by passengers wanting fresh air earlier in the night. Every open porthole was a death sentence for the ship.

The Technical Challenges of Modeling the Atlantic

Simulating water is the "final boss" of computer graphics.

In a Titanic sinking simulation, you can't just use a flat plane for the ocean. You have to account for the displacement. When a ship that big moves through the water, it creates its own currents. Then there’s the "suction" myth. For years, people thought the sinking ship would suck swimmers down with it. Modern fluid dynamics simulations suggest this didn't really happen. The ship displaced so much water that it actually pushed things away as it settled, though the localized turbulence was obviously fatal.

Then you have the descent. The sinking doesn't stop at the surface.

The bow, being aerodynamic (or "hydrodynamic"), slid through the water at about 25-30 miles per hour, landing relatively softly on the seabed two miles down. The stern, however, was a chaotic mess. It spiraled. It lost pieces. It hit the bottom with such force that it buried itself deep in the silt.

What We Still Get Wrong

Even the best simulations have limitations.

We still don't know the exact moment the lights went out. We know it was right before the breakup, but the specific failure of the electrical engineers—who stayed at their posts to the very end—is hard to model because we don't know which dynamos were submerged first.

Also, the "Iceberg Damage" is often misrepresented. It wasn't a huge gash. It was a series of small "fingers" of damage—narrow slits where the hull plates buckled and rivets popped. If the damage had been just a few inches shorter, the ship might have stayed afloat. It was a "perfect storm" of engineering limits.

📖 Related: How to Delete an Apple ID Without Ruining Your Life

Moving Beyond the Screen

To truly understand the Titanic disaster, you have to look past the pixels. While a Titanic sinking simulation provides the "how," it’s the historical records that provide the "why."

If you're interested in the technical side of the disaster, your next steps should be grounded in the actual data used to build these models.

- Review the 1912 Inquiry Transcripts: Search for the British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. Read the testimony of the surviving firemen and greasers who were in the boiler rooms. Their descriptions of the water coming in are what modelers use to "tune" the simulation speed.

- Explore the Debris Field Maps: Look at the sonar mapping provided by RMS Titanic Inc. Understanding where the boilers landed vs. where the "Big Piece" landed tells you everything you need to know about the ship's final moments of structural integrity.

- Study the Steel Analysis: Research the "Charpy V-notch test" performed on Titanic's steel. It explains the "ductile-to-brittle" transition that caused the hull to snap rather than bend in the cold water.

The simulation isn't just a movie. It’s a laboratory. Every time we update the physics, we learn something new about the most famous maritime disaster in history. We're not just watching a ship sink; we're watching the laws of physics at work in the most dramatic way possible.