Honestly, we all remember where we were during those four days in June 2023. The ticking clock on the news. The "banging sounds" that turned out to be nothing. The frantic search for a vessel the size of a minivan in an ocean the size of... well, the Atlantic. It was a global obsession. But now that the dust has settled and the Coast Guard’s Marine Board of Investigation has basically laid it all out, the reality is actually a lot more frustrating than the "mysterious disappearance" the media sold us.

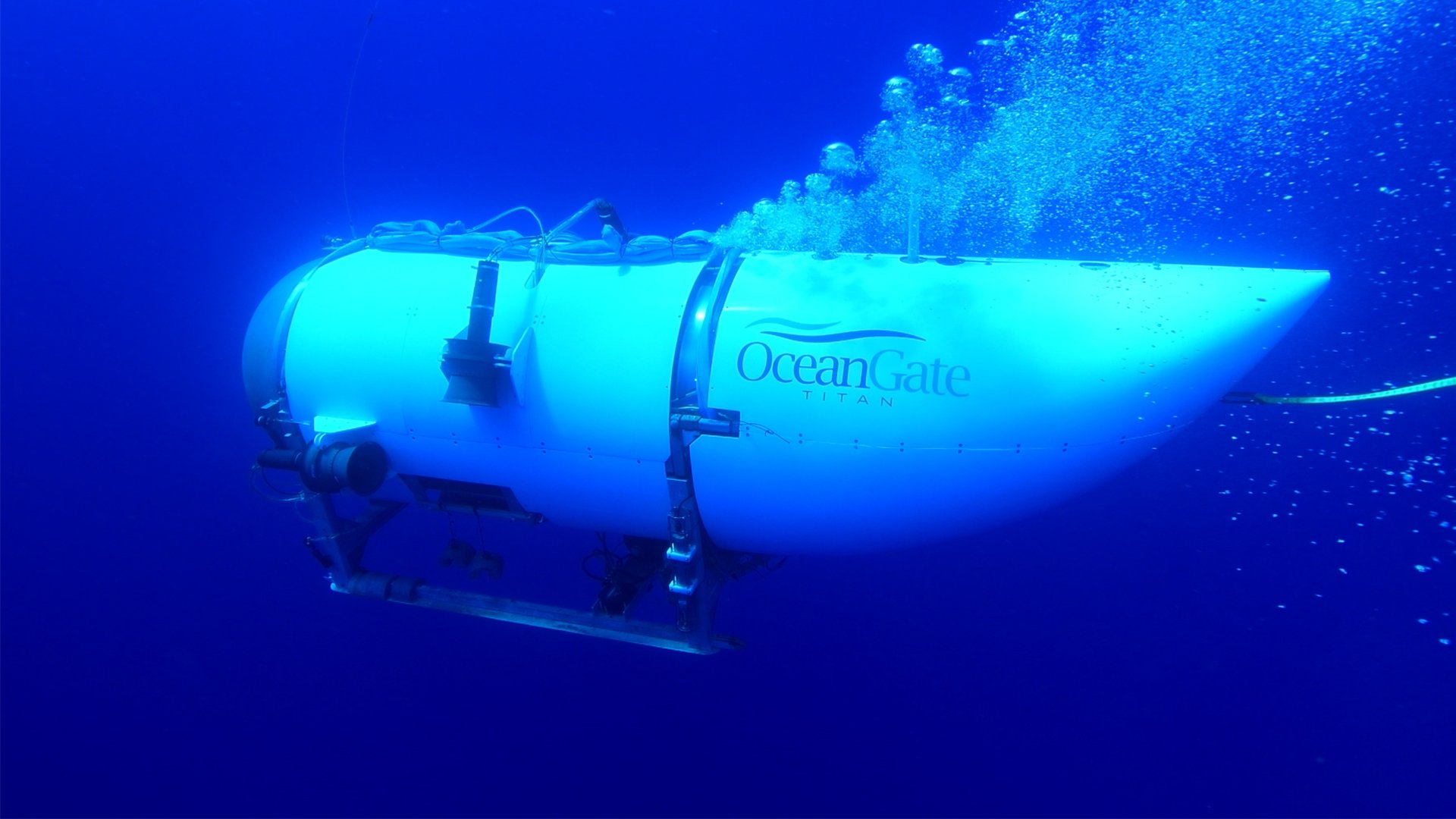

The Titan the OceanGate submersible disaster wasn't a freak accident. It wasn't "bad luck" or an unpredictable monster wave. It was an engineering train wreck that had been predicted for years by almost everyone in the deep-sea community.

The "Innovation" That Wasn't

Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate, loved to talk about breaking rules. He famously told Mexican YouTuber Alan Estrada that he wanted to be remembered as an innovator. He basically felt that the "established players" in the submersible industry were stifling progress with too many safety regulations.

But here is the thing: underwater physics doesn't care about your disruption.

Most deep-sea submersibles, like the famous Alvin or James Cameron’s Deepsea Challenger, use spherical hulls made of titanium or thick steel. Why? Because those materials shrink and expand predictably under pressure. Rush decided to use a cylindrical hull made of carbon fiber. It was cheaper. It was lighter. It allowed him to fit five people inside instead of the usual two or three.

Why carbon fiber was the smoking gun

Carbon fiber is amazing for planes because it's strong and light under tension (pulling apart). But the deep ocean is all about compression (crushing in).

When you go down to the Titanic—about 12,500 feet deep—the pressure is roughly 5,800 pounds per square inch. That is like having an elephant stand on your thumb. Carbon fiber is a composite; it’s layers of fabric glued together. Under that kind of weight, any tiny imperfection, any microscopic bubble in the glue, or any slight delamination becomes a failure point.

💡 You might also like: Michael Collins of Ireland: What Most People Get Wrong

James Cameron, who has been to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, pointed out the "terrible irony" of the whole thing. The Titanic sank because the captain ignored warnings about ice. The Titan the OceanGate submersible disaster happened because the CEO ignored warnings about his hull.

The Warning Signs Nobody Listened To

It's kinda wild how many people tried to stop this. In 2018, more than 30 experts from the Marine Technology Society wrote a letter to Rush. They told him his "experimental" approach could lead to "catastrophic" results.

He basically told them they were trying to stop him from innovating.

Then you had David Lochridge, OceanGate's former Director of Marine Operations. He raised hell about the fact that the hull hadn't been properly scanned for flaws. He wanted non-destructive testing—basically an X-ray for the hull—to make sure those carbon fiber layers weren't separating. Instead of listening, OceanGate fired him and sued him for breaching a non-disclosure agreement.

"I don't want to be a billionaire. I just want to go to the Titanic." — A sentiment often echoed by those who paid $250,000 for a seat, unaware of the internal safety wars.

The "Banging" and the Charade

Remember those "banging sounds" every 30 minutes? The world held its breath. People were calculating how much oxygen was left down to the minute.

📖 Related: Margaret Thatcher Explained: Why the Iron Lady Still Divides Us Today

It was all a fantasy.

We now know, thanks to the U.S. Navy’s top-secret acoustic detection system, that the Titan the OceanGate submersible disaster happened almost exactly when the sub lost contact on Sunday morning. The "bang" was the implosion. The search was a recovery mission from the start, even if the public didn't know it yet. The sounds heard later were just ocean noise or the search vessels themselves.

What Really Happened in Those Final Seconds

People ask if the crew suffered. The short answer is no.

At that depth, an implosion happens in about two milliseconds. For context, it takes your brain about 150 milliseconds to even process a visual stimulus. By the time the carbon fiber hull gave way, the air inside compressed so fast it briefly reached temperatures near the surface of the sun.

The passengers—Stockton Rush, Hamish Harding, Paul-Henri Nargeolet, Shahzada Dawood, and his 19-year-old son Suleman—wouldn't have felt a thing. They were gone before their nerves could even send a signal to their brains.

The Real Victims

It's easy to look at the billionaires and think "they knew the risks." But Suleman Dawood was just a kid who reportedly went because he wanted to please his dad for Father's Day. He even brought a Rubik's Cube to try and break a world record at the bottom of the ocean.

👉 See also: Map of the election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

And then there’s Paul-Henri Nargeolet. He was "Mr. Titanic." He had been down there dozens of times. His presence gave the whole operation a veneer of legitimacy that it probably didn't deserve. People thought, "If PH is on it, it must be safe."

Why This Matters in 2026

You’d think this would have ended private deep-sea tourism, right? Nope.

If anything, the Titan the OceanGate submersible disaster has created a massive divide. On one side, you have the "cowboy" explorers who think risk is just part of the game. On the other, you have the professional oceanographic community that is now pushing for much stricter international laws.

The problem is that OceanGate operated in international waters. They launched from a Canadian ship, used a U.S.-based company, and dived in a spot where no single country has total jurisdiction. This "regulatory vacuum" is exactly what allowed Rush to skip the "certification" or "classing" process that almost every other sub in the world goes through.

Actionable Insights for the Future of Exploration

If you're ever looking at "extreme tourism" or high-stakes adventure, here is how to spot a red flag:

- Check for "Classing": Real submersibles are certified by third parties like the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) or DNV. If a company says they are "too innovative" for certification, run.

- Redundancy is King: The Titan used a gaming controller to steer. While that’s actually common (the military uses them), the lack of backup systems was the issue.

- Listen to the Whistleblowers: In the age of the internet, you can usually find out if a company's former engineers are unhappy. Lochridge’s lawsuit was public record long before the implosion.

- Material Science over Marketing: Carbon fiber is great for bikes. It’s questionable for deep-sea pressure vessels. If the design deviates from 50 years of proven physics, there better be a mountain of peer-reviewed data to back it up.

The ocean is not a playground. It is a high-pressure environment that is fundamentally hostile to human life. The Titan the OceanGate submersible disaster taught us that you can't "move fast and break things" when those things are holding back the weight of the entire Atlantic Ocean.

To stay informed on the final legal rulings from the Marine Board of Investigation, you should follow the official U.S. Coast Guard newsroom updates, which are still releasing specific technical findings regarding the adhesive failure between the titanium rings and the carbon hull. Be wary of any deep-sea excursion company that refuses to provide third-party safety certification documents upon request.