Most of us remember the soft click-clack of the rails and that iconic, cheerful whistle. It’s childhood distilled into a few minutes of television. But if you grew up watching Thomas the Tank Engine, you probably didn't realize that the "Island of Sodor" was actually a series of cramped, sweat-filled soundstages in South England. The magic wasn't digital. It was physical.

Creating Thomas the train behind the scenes was a logistical nightmare that would make a modern CGI animator weep. We're talking about massive 1:32 scale models, tiny remote-controlled eyeballs, and enough cigarette lighter fluid to make a fire marshal nervous.

The Secret World of Gauge 1

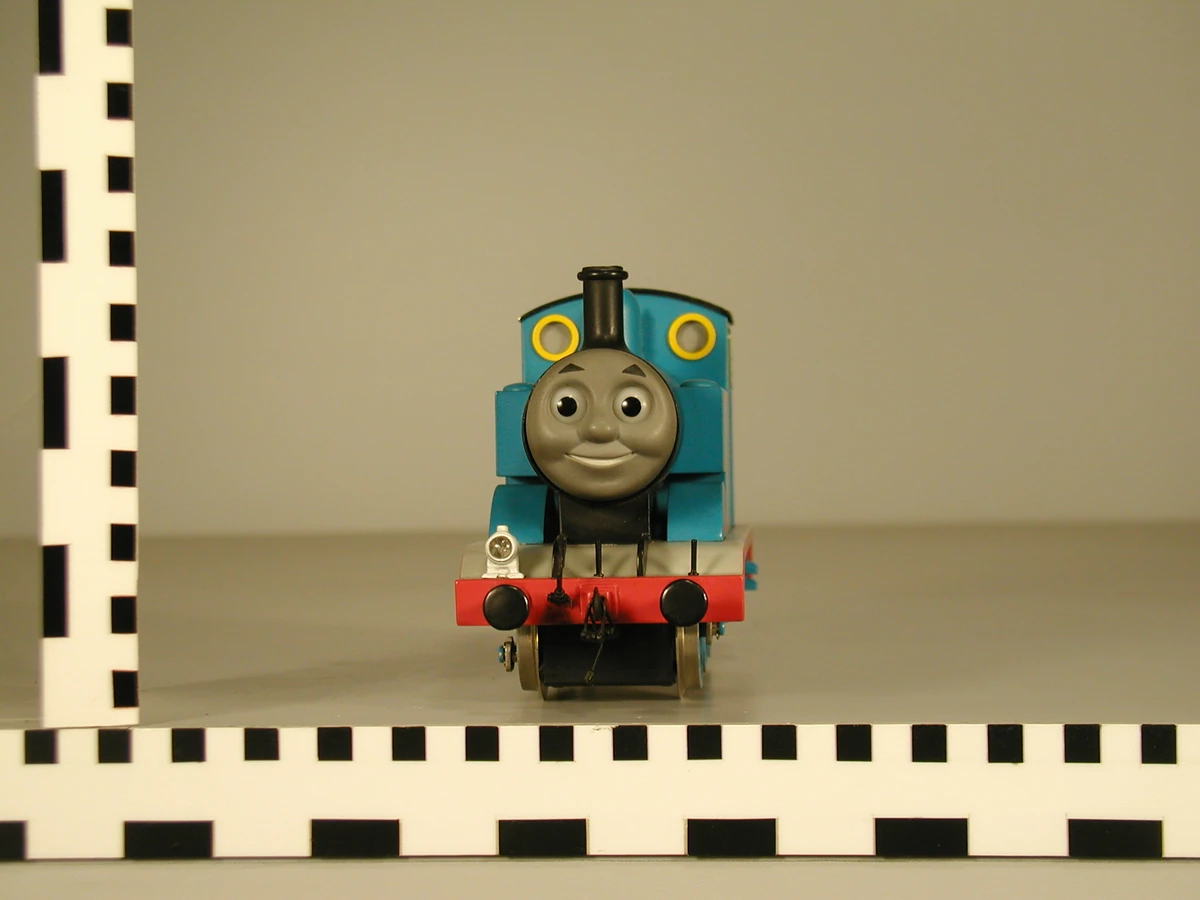

People always ask if the trains were "real." Well, they weren't toys you could buy at a local shop. The production used Gauge 1 models, which are significantly larger than the standard HO or OO scale sets most hobbyists keep in their basements. Thomas himself was about the size of a large toaster.

These models were heavy. They were made of brass and white metal, often built on top of German-made Märklin chassis for reliability. But "reliability" is a relative term in the 1980s.

Moving Eyes and "Supermarionation"

Have you ever noticed how the engines’ eyes move? That wasn't stop-motion. It was a technique inspired by Thunderbirds, often called Supermarionation. Inside each engine's hollow shell sat tiny radio-controlled servos—the kind used in RC airplanes.

A technician off-camera would move a joystick to make Thomas look left, right, up, or down. Honestly, it was a mess at first. In the early pilot episodes, the radio interference from the studio lights would sometimes make the eyes spin wildly in circles, making the engines look like they were having a breakdown. They eventually had to shield the electronics with lead foil.

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The Face Problem

The faces didn't move. At least, not while the camera was rolling.

To get a "smile" or a "shocked" expression, the crew had to physically pop the face off the front of the engine and stick a new one on with a bit of blue tack or putty.

- The Original Faces: Sculpted from clay, then cast in resin.

- The Variety: By the mid-90s, the crew had hundreds of faces in storage for every character.

- The "Static" Look: This is why characters often have the same expression for an entire scene. Changing a face meant stopping the shoot, resetting the lighting, and hoping the engine hadn't shifted a millimeter.

Why the Smoke Was Actually Dangerous

That "chuff-chuff" smoke coming out of the funnels? That was one of the biggest headaches for director David Mitton.

They used a modified car cigarette lighter to heat up a special oil. It created a beautiful, thick white plume. It also created a lot of heat.

If the crew left the smoke generator on for too long, the plastic resin of the engine’s body would literally start to melt. There are stories from the set of Thomas's "boiler" sagging because the heating element got too hot during a long take.

Later on, they switched to a safer "sugar-based" smoke fluid, but the early years were pure, old-school practical effects grit.

The Massive Scale of Sodor

One of the biggest misconceptions about Thomas the train behind the scenes is that it was one giant, permanent layout. It wasn't. The studio space at Shepperton was big, but not that big.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

The crew built "modules." If they needed a forest scene, they'd spend days setting up trees, moss, and dirt on a raised platform. Once the shots were done, they tore it down and built a harbor or a quarry in its place.

Keeping It "Real"

The "grass" was often dyed sawdust or specialized scenic foam.

The "water" in the early seasons? Often just colored resin or, in some cases, actual water with thickeners to make it look "heavier" so it didn't look like tiny droplets on camera.

David Mitton was a stickler for realism. He didn't want it to look like a toy set. He used "periscope" lenses that sat low to the track. This forced the perspective, making the engines look massive and the world look vast. When you see a shot of Gordon thundering past, the camera is usually just an inch off the ground.

The Transition to CGI: Why Everything Changed

By 2009, the physical models were retired. It was a business decision, mostly.

Maintaining a fleet of 50+ brass engines and hundreds of hand-painted sets was incredibly expensive. Plus, children’s television was moving toward the "active" look of CGI where characters could jump, walk, and—most importantly—move their mouths.

The transition happened in two stages:

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

- Series 12: A weird hybrid. They used the real models but "pasted" CGI faces onto them.

- Series 13 Onward: Full CGI. Nitrogen Studios in Canada took over, digitally scanning the original models to ensure the proportions remained exact.

Many fans still prefer the "Model Era." There’s a weight to the old footage that digital pixels can’t quite replicate. When a model engine crashed into a "brick" wall made of painted cork, it felt like a real accident because, well, things were actually breaking.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of Sodor, there are a few things you can actually do to see this history for yourself.

- Visit the Heritage Rail: Many of the original "hero" models are now kept in museums or private collections. The Hara Model Railway Museum in Japan actually houses a significant number of the original gauge 1 models used in the show.

- Watch the "Blooper" Reels: You can find leaked behind-the-scenes footage on YouTube where you see the crew’s hands adjusting the engines or the "invisible" wires used to make Harold the Helicopter fly.

- Check the Scale: If you’re a modeller, look for "Gauge 1" (1:32 scale). It’s the closest you’ll get to the actual size of the show's props.

The legacy of the Island of Sodor isn't just in the stories; it's in the incredible craftsmanship of the model makers who spent years gluing tiny pebbles to tracks just to make a three-minute story feel like a whole world.

To see the difference for yourself, try watching a "Model Era" episode (Series 1-7) back-to-back with a modern CGI episode. Pay attention to the way the light hits the paint on the engines. In the old versions, you can sometimes see the faint brushstrokes or a bit of dust—those are the fingerprints of the humans who built Thomas.