History books usually treat Thomas Paine like a dusty portrait on a wall, but honestly, he was more of a 1700s version of a viral podcaster or a firebrand journalist. If you’ve ever felt like the world was fundamentally broken and needed a hard reset, you’re basically channeling the original writer of Common Sense. He didn't just write a pamphlet; he shifted the entire vibe of a continent.

Before January 1776, most American colonists were actually still on the fence about Britain. They were annoyed about taxes, sure, but they weren't necessarily ready to burn the whole thing down. Then comes Paine. He wasn't a fancy aristocrat. He was a guy who’d failed at basically everything—staymaker, excise officer, teacher—before showing up in Philadelphia with a letter of recommendation from Benjamin Franklin.

He was the ultimate outsider.

The Viral Logic of the Writer of Common Sense

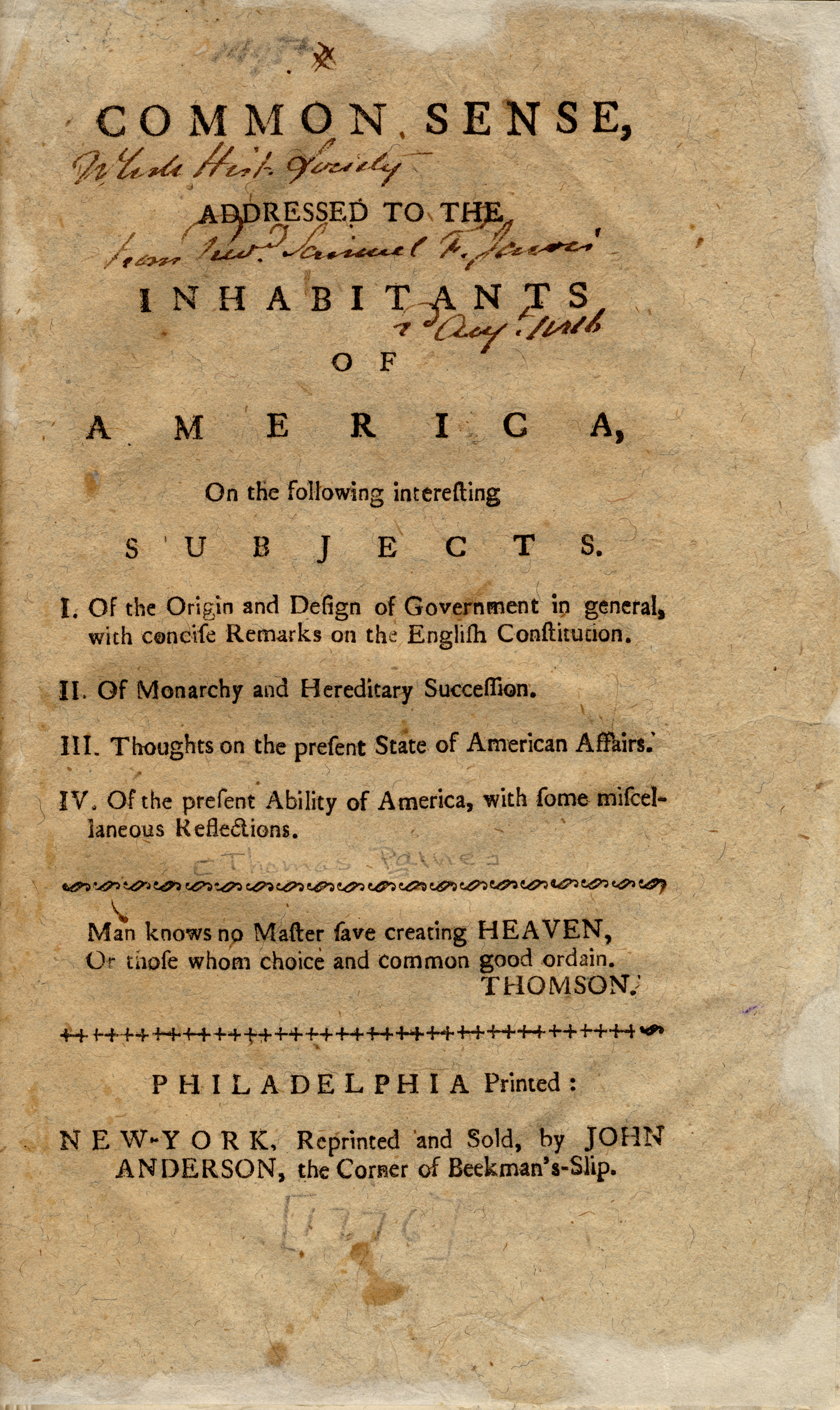

You have to understand the media landscape of the time. There was no TikTok. No TV. If you wanted to change minds, you printed small, cheap booklets. Common Sense was different because it didn't use Latin or flowery legal jargon that only lawyers could understand. Paine wrote for the guy at the tavern. He wrote for the farmer who was tired of being told what to do by a king who lived 3,000 miles away.

It was punchy. It was rude.

Paine basically looked at the idea of "divine right of kings" and called it a joke. He argued that if a king is "crowned" by God, then why do so many kings turn out to be idiots? It’s a fair point. He used the term "Royal Brute" to describe King George III, which was basically the 18th-century equivalent of a massive Twitter ratio.

📖 Related: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

Common Sense sold roughly 120,000 to 150,000 copies in its first few months. In a population of about 2.5 million people, that’s an insane saturation rate. It would be like a book selling 20 million copies today in the US alone. People were reading it out loud in public squares. It wasn't just a "good read"; it was the spark that turned a collection of grumpy colonies into a revolutionary force.

Why Paine’s Style Still Hits Different

Most writers back then were trying to sound like Roman senators. Not Paine. He used short, jagged sentences. He used analogies about families and nature.

"A government of our own is our natural right: And when a man seriously reflects on the precariousness of human affairs, he will become convinced, that it is infinitely wiser and safer, to form a constitution of our own in a cool deliberate manner, while we have it in our power, than to trust such an interesting event to time and chance."

He understood human psychology. He knew that if you make an argument feel like "common sense," people feel smart for agreeing with you. If you make it feel like a complex legal theory, they just feel tired.

It Wasn't Just About America

Paine is often pigeonholed as an American figure, but he was a global agitator. After the American Revolution, he went back to Europe and got deeply involved in the French Revolution. This is where he wrote Rights of Man. He was actually elected to the French National Convention despite not speaking French very well. Talk about confidence.

👉 See also: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

But here’s the thing: being a professional disruptor has a shelf life. Paine eventually turned his "common sense" logic toward religion in The Age of Reason. That didn't go over well. He criticized organized religion and the literal interpretation of the Bible, which, in the late 1700s, was a great way to lose all your friends.

When he died in New York in 1809, only six people attended his funeral. It’s a tragic end for a guy who literally talked a nation into existence. He was too radical even for the radicals.

The Misconceptions We Need to Clear Up

- He wasn't an atheist: People often label him one because of The Age of Reason, but he was a Deist. He believed in a creator but thought organized religion was a tool for power.

- He didn't make a dime off Common Sense: He donated his share of the profits to the Continental Army. He was broke for a huge portion of his life.

- He wasn't a "Founding Father" in the traditional sense: He didn't sign the Declaration or the Constitution. He was the guy who convinced everyone else that signing them was a good idea.

How to Apply "Common Sense" Logic Today

If we're being real, the way the writer of Common Sense approached problems is actually a masterclass in modern communication. He didn't wait for permission to have an opinion. He didn't care about "tradition" if that tradition was making people's lives miserable.

To think like Paine, you have to look at the systems around you—whether it's your job, your local government, or even your social circles—and ask: "Is this here because it works, or just because it's always been here?"

1. Strip Away the Jargon

Paine’s superpower was translation. He took high-level political philosophy (think John Locke) and turned it into street talk. If you can't explain your idea to a teenager or someone outside your industry, you don't understand it well enough. Paine proved that the simplest explanation is usually the most dangerous one for the status quo.

✨ Don't miss: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

2. Focus on the "Injustice" Factor

Common Sense worked because it validated the anger people already felt. He didn't just give facts; he gave those facts a moral backbone. He made people feel that staying under British rule wasn't just inconvenient—it was an insult to their dignity as humans.

3. Take the Financial Hit for the Mission

Paine was a nightmare to manage, but his integrity was undeniable. By refusing to profit from his most famous work, he made it impossible for his enemies to claim he was just a grifter. In an age of influencers and sponsored content, there’s something genuinely refreshing about a guy who just wanted the idea to win.

The Reality of Being a Disruptor

Being the writer of Common Sense sounds cool in a history book, but in real life, it was exhausting. Paine was imprisoned in France and nearly executed. He was harassed in the press. He died in relative obscurity.

The lesson here isn't necessarily that you should go out and start a revolution that ruins your social standing. It’s that ideas have a life of their own. Paine’s words outlived his reputation. They outlived his poverty. They even outlived the British Empire's hold on the Americas.

We often think we need a massive platform or a million followers to change things. Paine had a printing press and a lot of nerve. He didn't have a "strategy" beyond telling the truth as he saw it, as loudly as possible.

Actionable Insights for Modern Writers and Thinkers

If you want to channel the spirit of Thomas Paine in your own work or life, stop trying to be "balanced" when you know something is wrong. Balance is for accountants; clarity is for leaders.

- Read the original text: Don't just take a historian's word for it. Common Sense is surprisingly readable today. It’s short. You can finish it in an afternoon.

- Identify your "Royal Brutes": What are the outdated "kings" in your life? Maybe it's a corporate culture that's stuck in 1995 or a personal habit that no longer serves you. Use Paine’s method: call it what it is, mock its absurdity, and propose a clean break.

- Write for the tavern, not the ivory tower: Whether you’re sending an email or writing a blog post, cut the corporate-speak. Use "I" and "you." Be human.

- Don't fear the fallout: Paine was a pariah by the time he died because he wouldn't stop poking the bear. While you don't have to go that far, recognize that if everyone likes what you're saying, you're probably not saying anything new.

Thomas Paine proved that one person with a clear argument can outweigh an entire army. He wasn't perfect—he was stubborn, prone to drinking too much, and famously difficult to get along with—but he was the exact voice the world needed in 1776. He remind us that "common sense" isn't always common, and sometimes, it takes a radical to point out the obvious.