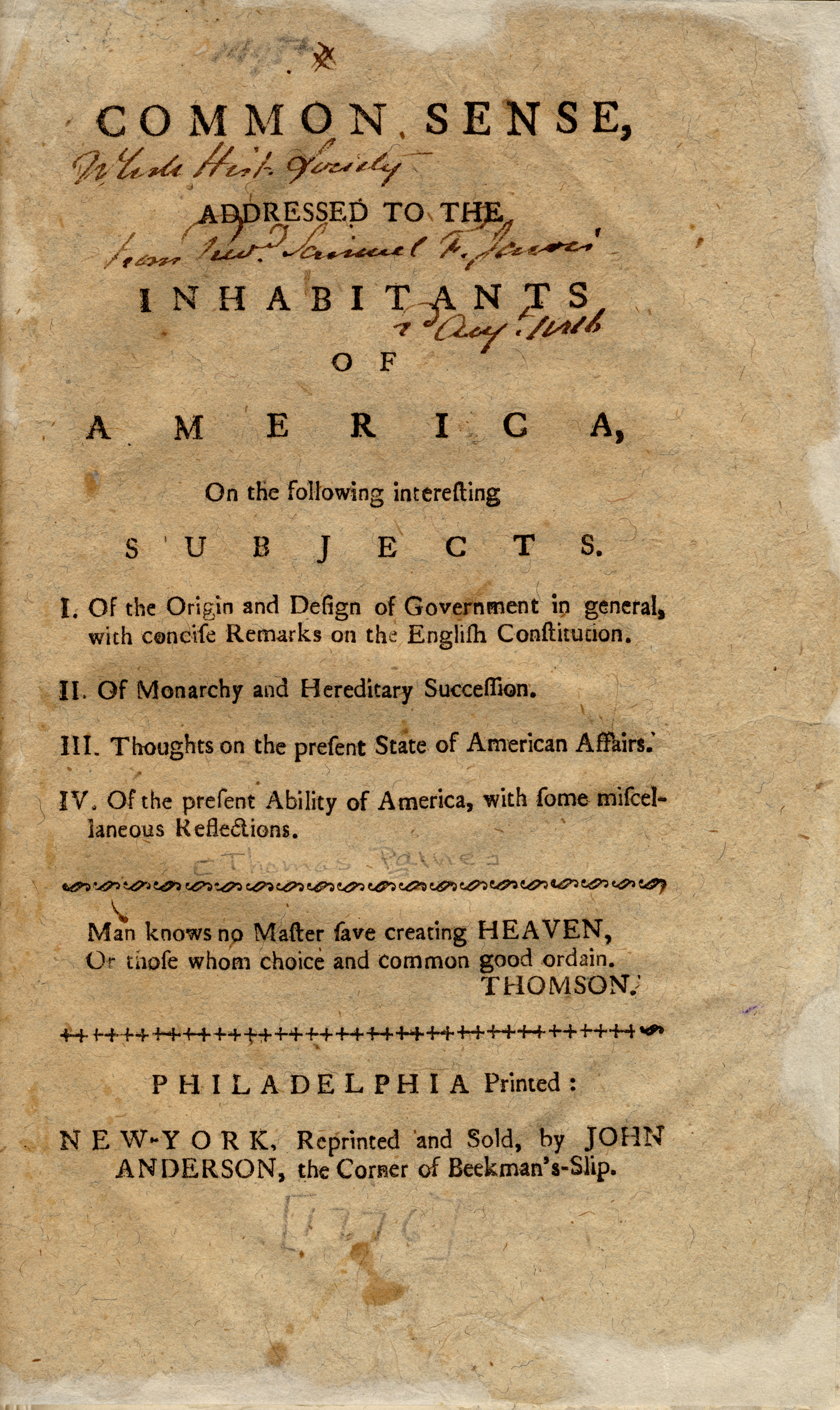

He was a failure. Honestly, if you looked at Thomas Paine’s life before 1774, you wouldn’t have bet a single shilling on him. He failed as a corset maker. He failed as a tax collector—twice. His first wife died young; his second marriage ended in a legal separation. By thirty-seven, he was basically adrift. Then he met Benjamin Franklin in London, got a letter of recommendation, and hopped on a boat to Philadelphia. He nearly died of typhus during the crossing. But he survived, and within a year, this "nobody" became the most influential writer of Common Sense, a pamphlet that didn't just suggest independence—it demanded it in a language that regular people actually spoke.

History books often treat the American Revolution like a polite debate between guys in powdered wigs. It wasn't. It was messy, terrifying, and deeply uncertain. Before January 1776, most colonists were still hoping for a reconciliation with King George III. They blamed Parliament, not the Crown. Paine changed that overnight. He didn't use Latin. He didn't quote obscure legal scholars. He used the Bible and plain English to call the King a "royal brute." It was a gutsy move. It was also treason.

The Viral Success of a 47-Page Pamphlet

You’ve got to understand the scale of this. In 1776, Common Sense sold roughly 120,000 copies in its first three months. Some estimates suggest up to 500,000 copies circulated in total during the war. In a population of about 2.5 million people (including enslaved people who were largely kept illiterate by law), that’s the equivalent of a modern book selling 60 million copies in ninety days. It was the biggest bestseller in American history relative to the population.

People read it aloud in taverns. They debated it in blacksmith shops. It worked because Paine understood something that the elite "Founding Fathers" didn't: if you want to start a revolution, you have to talk to the people doing the fighting, not just the people doing the legislating. He wasn't just a writer of Common Sense; he was a master of media. He refused to take the profits from the book, donating them to purchase mittens for the Continental Army. Imagine a penniless immigrant giving up a fortune because he believed in the "cause of mankind." That’s not just writing; that’s skin in the game.

Why the Tone Mattered

Paine’s writing style was a middle finger to the establishment. At the time, political writing was stuffy. It was "high-brow." Paine wrote with a rhythmic, pounding urgency. Take his opening: "Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one."

🔗 Read more: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Simple. Brutal. Effective.

He didn't argue that the British tax on tea was a violation of the Magna Carta. Instead, he argued that a small island across the sea had no business governing a whole continent. He called the idea of hereditary monarchy "ridiculous." He mocked the "divine right of kings" by pointing out that if you trace any royal bloodline back far enough, you just find a "principal ruffian" who happened to be the best at hitting people over the head.

Beyond the Battlefield: The Radical Ideas We Forget

We focus on the "independence" part because that’s what made the U.S. a country. But as a writer of Common Sense, Paine was pushing for things that were way ahead of his time. He wasn't just a patriot; he was a radical democrat. He wanted a massive expansion of the right to vote. He wanted a representative government that actually looked like the people it served.

Later in his life, in Agrarian Justice, he proposed a primitive form of Social Security and a basic income. He thought that because the earth was the "common property of the human race," people who owned land owed a "ground-rent" to the rest of society. He wanted to give every person a sum of money when they turned twenty-one to help them start a life, and a pension for everyone over fifty. In 1797. Let that sink in.

💡 You might also like: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

The Backlash and the Loneliness

Being the writer of Common Sense didn't lead to a comfortable retirement. Paine was too radical for the very men he helped empower. When he went to France to help with their revolution, he ended up in prison because he was too moderate for Robespierre (he opposed executing the King). Then, he wrote The Age of Reason, which attacked organized religion and the literal interpretation of the Bible.

That was it. The public turned.

When he returned to America in 1802, he was a pariah. People forgot he was the guy who wrote The American Crisis—the text George Washington ordered to be read to the troops at Valley Forge to keep them from deserting. When Paine died in 1809, only six people attended his funeral. Two of them were Black men, which says a lot about who still valued his message of universal human rights.

What We Get Wrong About Paine’s "Common Sense"

Most people think "common sense" just means "good judgment." But for Paine, it was a philosophical stance. He believed that political truth wasn't something you needed a law degree to understand. He believed it was accessible to anyone with a functioning brain.

📖 Related: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

- Myth: He was an atheist.

Reality: He was a Deist. He believed in God but hated organized churches, which he saw as tools to keep people uneducated and submissive. - Myth: He was a typical "Founding Father."

Reality: He was an outsider. He never owned a home until late in life, never held significant office, and died in poverty. - Myth: He only cared about America.

Reality: He saw the American Revolution as the first domino. He wanted the whole world to be free of kings. "My country is the world," he wrote, "and my religion is to do good."

Applying the "Writer of Common Sense" Mindset Today

Paine’s life is a masterclass in the power of the written word to disrupt a "fixed" system. If you’re trying to communicate an idea today—whether it's a business proposal, a blog post, or a political movement—his tactics still hold up. He didn't wait for permission to speak. He didn't wait for an elite institution to validate him. He just wrote the truth as he saw it, in the language of the street.

Take Action: Read the Source Material

Stop reading summaries. Seriously. Common Sense is short. You can read the whole thing in under two hours. If you want to understand the DNA of modern democracy, go to the source. You’ll find that a lot of the "original intent" people talk about today was actually much more radical and inclusive than we’re led to believe.

- Download or buy a copy of the "Common Sense" pamphlet. Look for an annotated version if you aren't familiar with 18th-century slang.

- Compare his 1776 arguments to modern political rhetoric. Notice how few people today speak with that level of directness.

- Check out "The Age of Reason." See why it made people so angry back then. It’s a fascinating look at the limits of free speech in the early Republic.

- Visit the Thomas Paine Cottage in New Rochelle, NY. It’s one of the few places that honors his actual physical footprint.

The legacy of the writer of Common Sense isn't just a footnote in a history book. It’s a reminder that one person with a pen (or a keyboard) and zero fear of the status quo can actually shift the world. Paine didn't have a platform until he built one. He didn't have a voice until he used it. He was a flawed, grumpy, brilliant man who dared to tell a King to get lost. We could use a little more of that energy today.