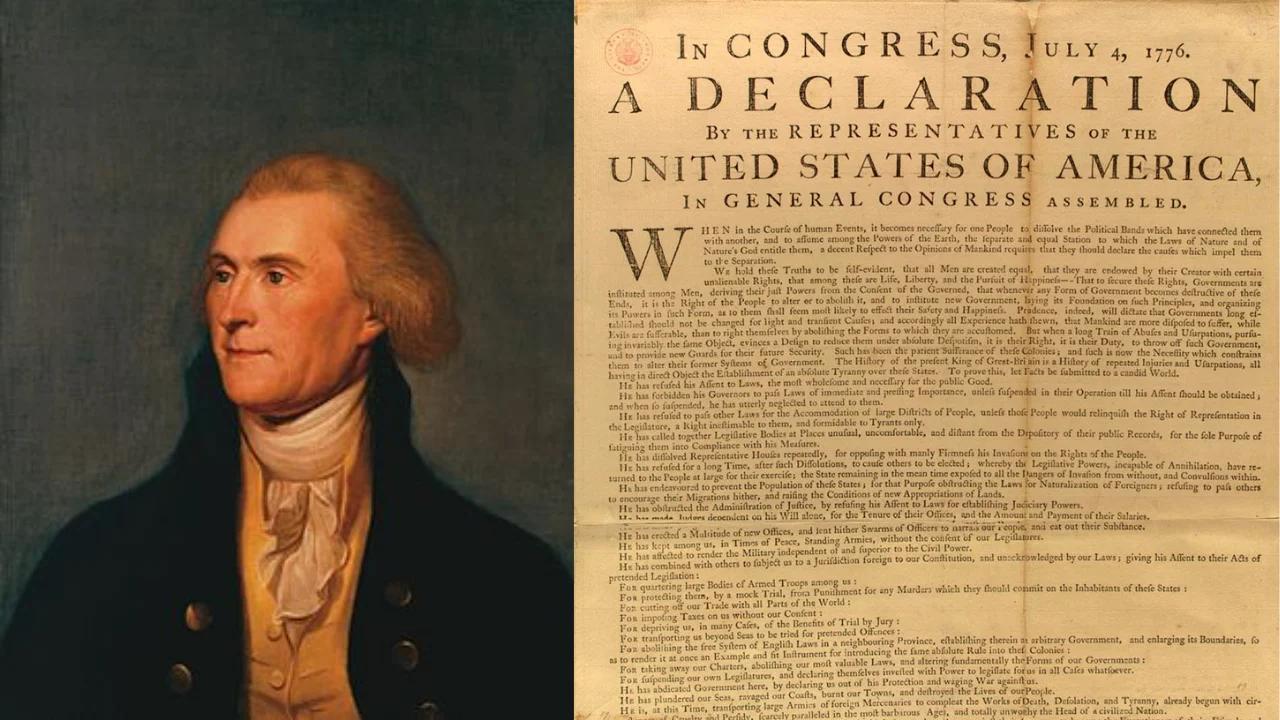

It is the great American paradox. You’ve probably seen the statue in D.C., or at least handled a nickel. Thomas Jefferson, the man who penned the soaring words "all men are created equal," spent his entire life supported by the labor of hundreds of people he claimed to own. It's messy. Honestly, it's more than messy—it’s a historical knot that scholars have been trying to untie for over two centuries.

When we talk about Thomas Jefferson and slavery, we aren't just talking about a "man of his time." That's a lazy shortcut. Jefferson was a philosopher who knew exactly what he was doing. He called slavery a "hideous blot" on the nation, yet he didn't stop it. He didn't even stop it at his own front door. He was a man trapped between his lofty Enlightenment ideals and the cold, hard reality of his debts, his lifestyle, and his own deep-seated prejudices.

The Brutal Reality of Monticello

Monticello is beautiful. The architecture is stunning, perched on a "little mountain" in Virginia. But beneath the surface of the fine wine and the massive library was a forced labor camp. That’s what it was. During his lifetime, Jefferson owned more than 600 people. While he was in Philadelphia or Paris talking about the rights of man, people like Jupiter Evans and Ursula Granger were doing the backbreaking work that allowed him to be an intellectual.

Jefferson wasn't a "kind" master in the way some old textbooks used to suggest. There is no such thing. While he preferred to use "moral suasion" rather than the whip, he didn't hesitate to use violence when the system demanded it. Records show that at the Monticello nailery—a small factory on the property—young enslaved boys were whipped to keep up production. Jefferson knew about it. He saw the reports.

He viewed himself as a benevolent father figure, a "Patriarch." It’s a bit nauseating when you think about it. He convinced himself that he was taking care of people who couldn't take care of themselves. Yet, he sold families apart to pay off his mounting debts. Between 1784 and 1794, Jefferson sold dozens of people. He knew it was wrong. He wrote about the "cruel" nature of the slave trade. But when the bank came calling, the humans he owned became line items on a ledger.

The Hemings Family and the DNA Evidence

You can't discuss Thomas Jefferson and slavery without talking about Sally Hemings. For years, historians dismissed the "rumors" of Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings as political slander from his enemies. Then came 1998. DNA testing conducted by Dr. Eugene Foster and his team proved a genetic link between the Jefferson male line and the descendants of Eston Hemings, Sally’s youngest son.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Sally Hemings was Jefferson’s property. She was also his late wife’s half-sister.

Think about that for a second.

She was about 14 when she accompanied Jefferson’s daughter to Paris. Jefferson was in his 40s. Under any modern definition, this wasn't a "romance." It was a relationship built on a profound power imbalance. However, it’s also complex. Hemings had a degree of leverage in Paris, where slavery was technically illegal. She negotiated for her children’s freedom before returning to Virginia. Jefferson kept his word, eventually freeing all of Sally’s children, though he never freed Sally herself. She remained "dead" to the tax rolls, living informally free in Charlottesville after his death.

Why Didn't He Just Free Them?

This is the question everyone asks. George Washington freed the people he enslaved in his will. Why didn't Jefferson?

The answer is partly financial and partly ideological. Jefferson was broke. Truly, deeply in debt. By the time he died in 1826, he owed the equivalent of millions of dollars. Under Virginia law at the time, enslaved people were considered property that could be seized by creditors. He couldn't free them because he didn't "own" them outright—the banks did.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

But there’s a darker reason. Jefferson was a white supremacist.

In his only published book, Notes on the State of Virginia, he wrote some of the most racist pseudo-science of the 18th century. He speculated that Black people were inferior to whites in both body and mind. He argued that if they were ever freed, they would have to be sent away—colonized elsewhere—because he believed the two races could never live together in peace. He feared a race war. He famously said, "We have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go."

He was scared. He was a man who preached bravery and revolution but was terrified of the social upheaval that true equality would bring.

The Legislative Failure

Jefferson had chances to change things. As a young lawyer, he took on pro-bono cases for enslaved people seeking freedom. In the original draft of the Declaration of Independence, he included a blistering paragraph blaming King George III for the slave trade. The Continental Congress struck it out. They didn't want to lose the support of South Carolina and Georgia. Jefferson backed down.

Later, in 1784, he proposed a law that would ban slavery in the new Western territories after the year 1800. It failed by a single vote.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

"The voice of a single individual would have prevented this abominable crime," Jefferson later wrote.

But as he got older, his fire faded. He became more concerned with "states' rights" and preserving the Union than with the individual rights of the people he enslaved. By the Missouri Compromise of 1820, he was siding with the expansion of slavery, fearing that restricting it would lead to the death of the Republic. He chose the Union over justice.

The Legacy We Live With

So, what do we do with this? We don't have to tear down the statues, but we have to tell the whole story. When you visit Monticello today, the guides talk about the "Enslaved Community." They don't hide the nailery or the Hemings family. They show you the tiny rooms where people lived under the South Terrace, just steps away from where Jefferson sat drinking fine French wine and writing about liberty.

The story of Thomas Jefferson and slavery is the story of America. It’s a story of incredible potential and devastating failure. It’s about the gap between who we say we are and what we actually do.

Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, exactly fifty years after the Declaration of Independence was adopted. He left his family in such debt that almost everyone he owned had to be sold on the West Lawn of Monticello to pay his bills. Families were shattered. The "blot" he hated remained.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you want to understand this topic beyond the surface level, don't just read a biography. Look at the primary sources. History is about the receipts.

- Visit the "Getting Word" Project: This is an oral history project at Monticello that tracks the descendants of the enslaved families. It shifts the focus from Jefferson to the people who actually built the place.

- Read "Notes on the State of Virginia": Specifically Query XIV. It’s uncomfortable. It’s racist. But it’s essential to see the actual thoughts of the man rather than the sanitized version.

- Study the 1784 Land Ordinance: Look at how close the U.S. came to banning slavery in the West decades before the Civil War. It’s one of the great "what ifs" of history.

- Compare Jefferson and Washington: Look at their wills. Compare their approaches to manumission. Washington wasn't a saint, but he took a step Jefferson refused to take.

- Explore the "Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello" Exhibit: If you can't go in person, their digital archives are some of the best in the world for seeing the daily lives, tools, and personal items of the enslaved community.