He is a little blue engine with a short, stumpy funnel and a short, stumpy boiler. If you have kids, or if you were once a kid with a pulse in the last eighty years, you know exactly who I’m talking about. But honestly, Thomas and Friends is a weird phenomenon when you really step back and look at it. We are talking about a multi-billion dollar franchise centered on sentient industrial machinery that frequently gets bricked up in tunnels as punishment or nearly scrapped for parts. It’s heavy stuff for a toddler.

Most people think it started with a TV show in the 80s. It didn’t. It started with a measles outbreak in 1942. The Reverend Wilbert Awdry's son, Christopher, was stuck in bed, and his dad started telling him stories about engines to pass the time. These weren't just fluffy fairy tales. Awdry was a railway enthusiast—a "gricer," in British slang—and he demanded technical accuracy. If an engine didn't have the right wheel arrangement or a realistic steam pressure issue, it didn't make the cut. That gritty realism is exactly why the Island of Sodor feels like a real place, even when the engines are chatting about their feelings.

The Reverend’s Iron Rule of Realism

The Railway Series books were the foundation. Awdry was notoriously prickly about his creation. He once famously got into a spat with the television producers because they put a character in a situation that wouldn't happen on a real railway. To him, Sodor wasn't a magical land; it was a geographically mapped-out extension of the British rail system located between the Isle of Man and Barrow-in-Furness.

Look at the character of Henry. In the early stories, he was a "bad steamer" because his firebox was too small for the poor-quality coal he was being fed. That is a hyper-specific mechanical engineering problem. It wasn't solved by magic or friendship; it was solved by buying high-grade Welsh coal. Eventually, after a crash, he was sent to Crewe to be rebuilt with a larger firebox. This level of detail is why adults still find themselves sucked into the lore. It feels grounded. It feels like history.

The Ringo Starr Era and the Stop-Motion Magic

When Britt Allcroft bought the rights to bring the books to the screen in the early 1980s, she made a gamble that changed everything. She hired Ringo Starr. Yes, that Ringo Starr. Having a Beatle narrate a show about trains gave it an immediate, understated "cool" factor that separated it from the high-pitched, frantic energy of other Saturday morning cartoons.

🔗 Read more: British TV Show in Department Store: What Most People Get Wrong

The aesthetic was also crucial. Before the era of cheap CGI, Thomas and Friends used live-action model animation. These were heavy, expensive brass models moving on massive sets. When you see smoke coming out of Thomas’s funnel, that’s actual smoke. When the water splashes, it’s real water. There’s a tactile weight to those early seasons that the modern "All Engines Go" reboot simply cannot replicate. You can practically smell the oil and the damp British countryside.

Why Sodor Can Be Surprisingly Dark

There is a meme-culture obsession with how "dystopian" Sodor is. You’ve probably seen the jokes about Sir Topham Hatt (the Fat Controller) being a rail-yard dictator. And yeah, "The Sad Story of Henry" is basically a psychological horror story for five-year-olds. Henry refuses to come out of a tunnel because he doesn't want the rain to spoil his green paint. So, the Fat Controller just... builds a wall and leaves him there.

"We shall leave you here for always and always and always," the narrator says.

It’s brutal. But Awdry’s world was one of consequences. If you are a "Really Useful Engine," you have a place. If you are vain, lazy, or reckless, the "Scrapyard" is a very real threat. This wasn't meant to be cruel; it was a reflection of the era the stories were written in. Post-war Britain was obsessed with utility and rebuilding. If a machine didn't work, it was melted down to make something that did.

💡 You might also like: Break It Off PinkPantheress: How a 90-Second Garage Flip Changed Everything

The Transition to CGI and the Great Divide

Around 2009, the show moved away from physical models to full CGI. For many purists, this was the beginning of the end. The faces became more expressive, sure, but the "gravity" of the world felt lost. Suddenly, Thomas could jump off the tracks or use his wheels like hands.

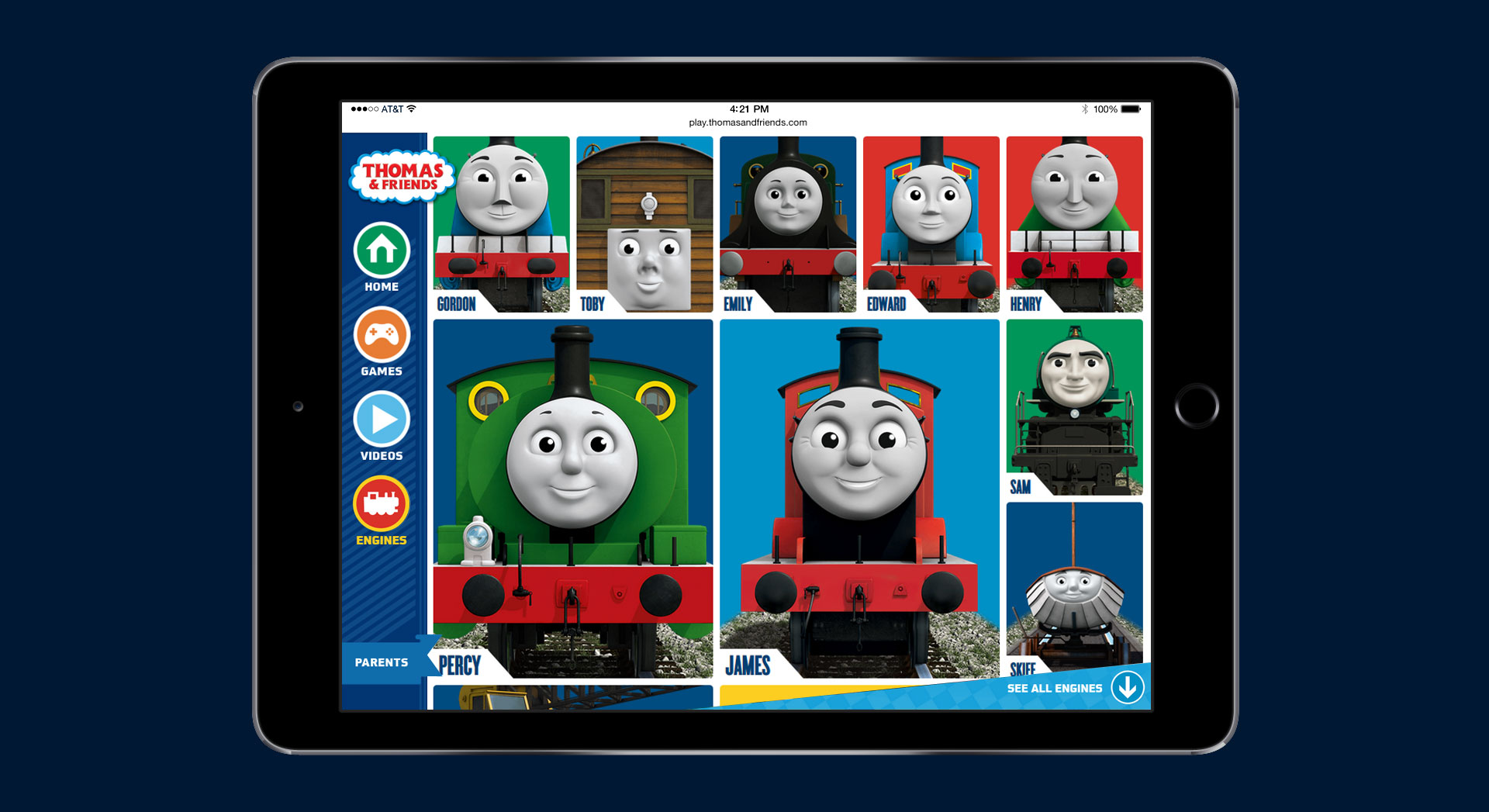

The newest iteration, All Engines Go, took this even further. It’s a 2D-animated show where the engines look like squishy toys. It’s designed for the YouTube generation—fast-paced, colorful, and bouncy. Old-school fans hate it. But Mattel, who now owns the brand, isn't looking at the 40-year-old hobbyists; they’re looking at the toddler market. The revenue from die-cast metal toys still keeps the lights on, and those toys sell better when the characters look like the cartoon on the screen.

The Real-World Impact of Thomas and Friends

The brand isn't just on screens. "Day Out with Thomas" events are a massive revenue stream for heritage railways across the globe. From the Strasburg Rail Road in Pennsylvania to the Nene Valley Railway in the UK, full-sized steam locomotives are painted blue and fitted with fiberglass faces.

For many small, struggling historical societies, Thomas is a financial savior. The families who pay for a ticket to see the blue engine are the ones funding the restoration of legitimate 19th-century rail history. It’s a weirdly symbiotic relationship between a fictional character and the preservation of actual industrial heritage.

📖 Related: Bob Hearts Abishola Season 4 Explained: The Move That Changed Everything

Misconceptions About the "Fat Controller"

Let’s clear something up: Sir Topham Hatt isn't a villain. In the books, he is often a father figure who genuinely cares for the engines. He frequently defends them against "The Railway Board" or outside inspectors who want to shut the line down. He is a buffer—pun intended—between the engines and the harsh reality of the nationalized British Railways (BR) that was actively "beeching" (closing down) small branch lines in the 60s. Sodor is a sanctuary where steam lives on, and he is the protector of that sanctuary.

Practical Steps for New Collectors or Parents

If you are just getting into the world of Thomas and Friends, either as a collector or for your kid, the marketplace is a minefield of different "systems." Here is how to navigate it:

- The Wooden Railway: This is the gold standard. The tracks are compatible with almost every generic brand (like IKEA or Brio). The engines are durable, hold their value, and feel great in the hand. Mattel recently "re-launched" this line to look more like the classic books, and they are beautiful.

- TrackMaster / Motorized: These are plastic and run on batteries. Great for kids who want to watch the trains move on their own, but the tracks take up a lot of floor space and the plastic gears tend to strip over time.

- Thomas & Friends Collectible Railway (Adventures/Take-n-Play): These are smaller, die-cast metal engines. They don't fit on the wooden tracks properly. Be careful not to mix these up when buying gifts.

If you want to experience the "real" Sodor, go back to the original Railway Series books by Wilbert Awdry. The prose is sparse but evocative. If you prefer watching, find the first four seasons of the original show. The practical effects and Ringo Starr/Michael Angelis narration provide an atmosphere that no modern cartoon can touch.

The Island of Sodor persists because it represents a world that works. The trains have jobs, the signals are clear, and everyone wants to be "Really Useful." In a world that often feels chaotic and digital, there is something deeply grounding about a steam engine trying his best to get a load of coal to the harbor on time. Even if he occasionally gets stuck in a tunnel.