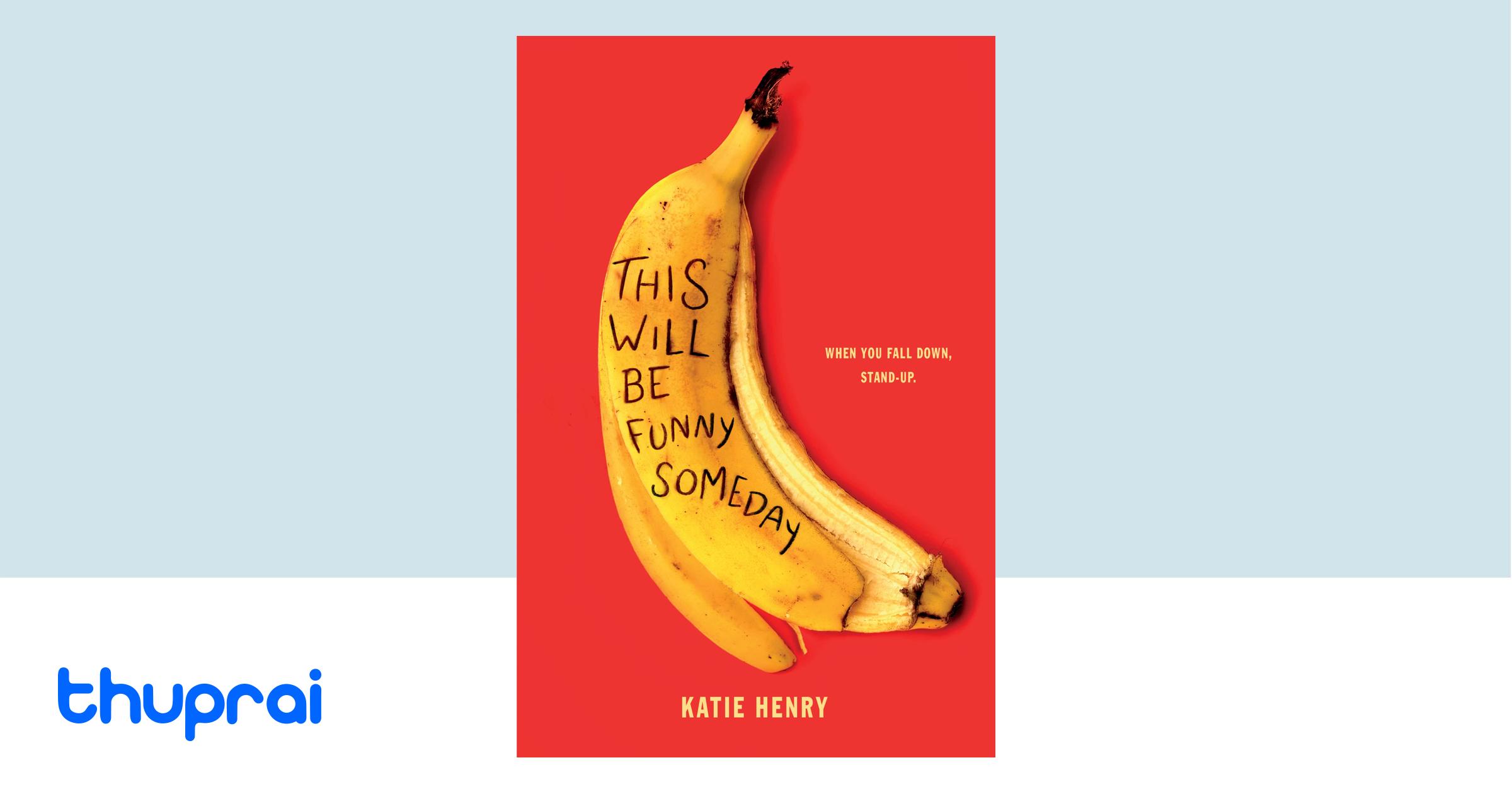

You're standing in the rain. Your car just broke down, your phone is at 1% battery, and you've somehow managed to spill hot coffee all over your white shirt. It feels like a catastrophe. But then, a tiny, annoying voice in the back of your head whispers: this will be funny someday. It’s a survival mechanism. Honestly, it’s probably the only thing keeping you from a total meltdown in the middle of the street.

Humor isn’t just about jokes. It’s about distance.

The phrase "this will be funny someday" isn't just a cope; it’s a psychological tool known as "temporal distancing." We use it to fast-forward through the trauma so we can look back at our current misery from a safe, comfortable future. It’s the art of transforming a tragedy into a "good story." We’ve all been there. You lose your luggage in a foreign country, or you trip and fall during a wedding toast. In the moment, it’s death. Six months later? It’s the highlight of the dinner party.

The Science of Tragedy Plus Time

Mark Twain is often credited with the formula: Humor = Tragedy + Time. It sounds simple. It’s actually quite profound. Researchers have spent years trying to figure out exactly how much "time" needs to pass before something moves from the "too soon" category into the "hilarious" one.

A study published in Psychological Science by Peter McGraw and his colleagues at the University of Colorado Boulder looked into this "Benign Violation Theory." Basically, for something to be funny, it has to be a "violation"—something that threatens your sense of how the world should work—but it also has to be "benign" or harmless.

When you’re in the middle of a disaster, it doesn’t feel benign. It feels like a threat.

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

Why distance makes the heart grow... funnier?

Distance can be physical, but more often, it’s chronological. The researchers found that a huge tragedy (like a natural disaster) becomes funnier as time passes because the threat level drops. Conversely, a tiny mishap (like stubbing your toe) is actually funnier right when it happens than it is five years later. No one cares that you stubbed your toe in 2019. But that time you accidentally joined a cult for a weekend because you thought it was a free yoga retreat? That’s gold, but only after you’ve safely escaped and processed the weirdness.

This Will Be Funny Someday as a Reframing Tool

We use this phrase to reclaim power. When you say this will be funny someday, you’re acknowledging that right now, things suck. You aren't gaslighting yourself into being happy. You're just acknowledging that your current state is temporary. It’s a gritty, realistic form of optimism.

Think about the most popular memoirs or stand-up specials. Usually, they aren't about how great everything went. They’re about the absolute train wrecks. David Sedaris has made a massive career out of things that were undoubtedly miserable when they occurred. From his eccentric family dynamics to his awkward attempts to learn French, he leans into the discomfort. He knows that the more specific and painful the detail, the more "this will be funny someday" becomes a reality.

- The awkward breakup: In the moment, you’re eating ice cream in bed. A year later, you’re laughing at the weirdly specific way they chewed their food.

- The job interview disaster: You realize later that the company was a sinking ship anyway, and your accidental "f-bomb" was just an early exit strategy.

- The travel nightmare: Missed flights and bedbugs are the ingredients for the only travel stories people actually want to hear.

When It’s Not Funny Yet (And Why That’s Okay)

There is a limit. Some things never become funny. We have to be honest about that. Chronic illness, deep grief, or systemic injustice often stay in the "tragedy" column indefinitely. The "this will be funny someday" mantra works best for "situational irony"—the stuff that happens to us that feels like a personal prank from the universe.

Psychologists call this "cognitive reappraisal." You’re changing the emotional trajectory of an event. By looking for the absurdity in a situation, you’re activating the prefrontal cortex. This helps dampen the response of the amygdala, which is the part of your brain currently screaming that the world is ending because you sent a "reply all" email complaining about your boss... to your boss.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

The Timing Sweet Spot

If you try to find the humor too early, it’s offensive. If you wait too long, the emotional "juice" of the story has evaporated. There’s a sweet spot—usually somewhere between three weeks and two years—where the embarrassment is still fresh enough to be relatable but distant enough to not cause a panic attack.

Why We Tell These Stories

Humans are social creatures. We use our failures to build bridges. If I tell you about my perfect day, you’ll probably find me annoying. If I tell you about the time I accidentally walked into the wrong hotel room and found a stranger sleeping, we’re best friends.

Sharing the moments that we promised ourselves this will be funny someday is a way of saying, "I’m human, I’m messy, and I survived." It creates a sense of psychological safety for everyone else. It gives others permission to laugh at their own disasters.

How to Lean Into the Absurdity

If you’re currently in the middle of a "this will be funny someday" moment, here is how you can actually use that mindset to survive the next hour without losing your mind.

Narrate the moment as a third party. Imagine you’re a narrator in a documentary about a particularly clumsy human. "Here we see the subject, having just dropped their entire grocery bag in the parking lot. Notice the way the eggs break in perfect synchronization." It sounds silly, but it creates that necessary distance.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

Write it down exactly as it’s happening. Don't wait for the polish of memory. Capture the raw, ridiculous details. The specific smell of the burnt toast. The exact words the mechanic said. These details are what make the story hilarious later. Without the grit, it’s just a generic complaint.

Look for the "benign violation." Ask yourself: "Is anyone actually in danger, or am I just deeply embarrassed?" If it’s just embarrassment, you’re already halfway to a punchline. Embarrassment is just your ego being bruised, and the ego is surprisingly resilient. It can take a few hits.

Find your "comedy partner." Everyone needs that one friend you can call who will laugh with you (and maybe a little bit at you) while you’re still in the crisis. They are the ones who help you bridge the gap between "this is a nightmare" and "this is a classic."

Recognize the "High Stakes" Fallacy. Most of the things we stress about feel like high stakes but are actually quite low. In five years, will this matter? Probably not. If it won't matter in five years, it's a prime candidate for the "this will be funny" treatment.

The next time you’re sitting in the dark because you forgot to pay the power bill, or you’re explaining to a cop why there’s a goat in your backseat (long story), just take a deep breath. Remind yourself that you are currently in the "inciting incident" of a future comedy bit. The more ridiculous it is now, the harder people will laugh later. You aren't just suffering; you're gathering material.

Practical Steps for Your Next "Disaster":

- Take one deep breath to lower your heart rate.

- Identify one specific detail that is objectively weird or ironic about the situation.

- Tell yourself, out loud if you have to: "This will be funny someday."

- Start thinking about who you're going to tell this story to first.

By the time you reach the end of the day, the tragedy will already be starting its slow, inevitable transformation into comedy. Let it happen. It's the best medicine we've got.