Ever walked past a massive, imposing old building and felt a shiver you couldn't quite explain? That's the ghost of the asylum. For centuries, we've tucked away the "mad" behind thick stone walls, hoping that out of sight meant out of mind. Mike Jay, a historian who honestly has a knack for finding the weirdest corners of our past, decided to tear those walls down—at least metaphorically.

His book, This Way Madness Lies, isn't just a dry history of doctors and charts. It’s a messy, beautiful, and deeply uncomfortable look at how we’ve treated—and mistreated—the human mind since the 1700s.

Basically, it’s the story of Bedlam. But not the horror-movie version you’re thinking of.

The Pendulum of "Curing" People

If you think mental health treatment has been a steady climb toward enlightenment, Mike Jay is here to tell you that’s just not true. It’s more like a pendulum. We swing from "lock them in a cage" to "let's give them a nice garden and some tea," and then back to "let's try some heavy-duty chemicals."

The book follows the evolution of the Bethlem Royal Hospital in London. Most people know it as Bedlam. Jay breaks this down into four distinct "lives" of the institution:

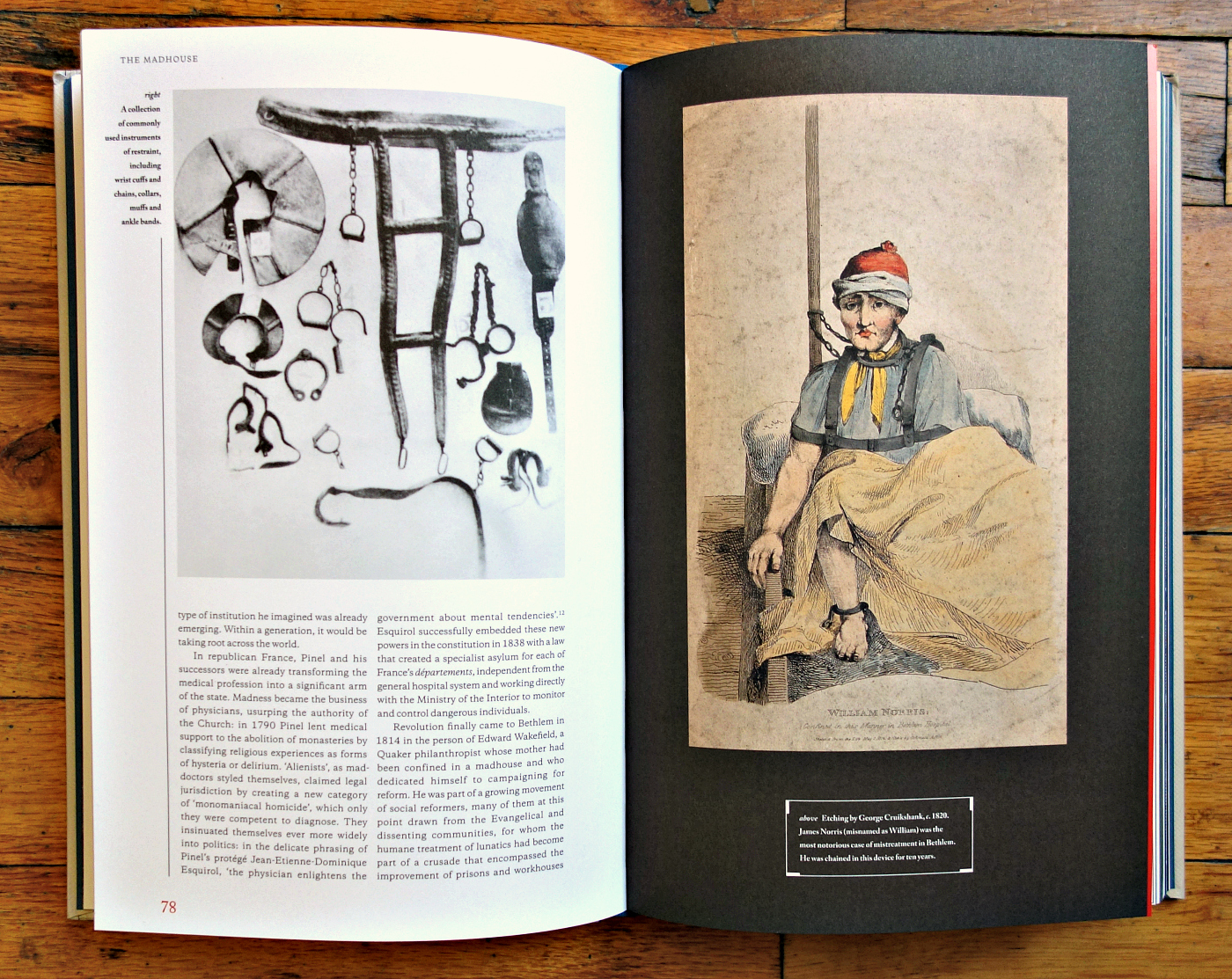

- The Madhouse (1700s): Think iron collars and chains. It was essentially a prison for the "unmanageable."

- The Lunatic Asylum (1800s): This was the "moral treatment" era. High ceilings, big windows, and the hope that fresh air could fix a broken spirit.

- The Mental Hospital (1900s): This is where it gets clinical. Lab coats, insulin shocks, and the first wave of tranquilizers.

- The Modern Era: The walls are gone, but the struggle is everywhere.

Jay’s big point? None of these eras really "solved" madness. They just changed the scenery.

📖 Related: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Why We Should Stop Thinking Bedlam Was Only a Horror Show

We love a good scary story. We picture 18th-century Bedlam as a dark dungeon where people were poked with sticks for a penny. And yeah, the public could visit Bedlam until 1770. It was a tourist attraction. Pretty gross by our standards, right?

But Jay adds some nuance that most people miss. To the people of the 1700s, "madness" was a public spectacle because they didn't see it as a private medical tragedy. It was a loss of reason, a lapse in the "human" part of the soul.

James Tilly Matthews is one of the most fascinating characters Jay introduces. He was a patient who believed a gang was using a machine called an "Air Loom" to influence the minds of politicians via magnetic vapors. Matthews actually drew detailed plans for a new Bethlem hospital while he was confined. A patient designing his own prison—it’s wild to think about.

The Art of the "Incurable"

One of the coolest things about This Way Madness Lies is the art. Jay worked with the Wellcome Collection to pull in over 600 illustrations. These aren't just diagrams of brains. They are paintings and sketches by the patients themselves.

Take Richard Dadd. He was a brilliant painter who killed his father during a psychotic episode and spent the rest of his life in Bethlem and Broadmoor. His work is incredibly detailed, almost obsessive. Then you have Louis Wain, famous for his psychedelic-looking cats.

👉 See also: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

Seeing this art changes the way you look at the "insane." It turns them from a "case study" into a person with a very vivid, if terrifying, inner world.

The Truth About the 20th Century "Cures"

When the 1900s rolled around, everyone was convinced science had the answer. Doctors were done with "moral treatment." They wanted results. This is the era of the Rosenhan experiment—where healthy people faked hallucinations to see if they’d be admitted to psychiatric hospitals (they were, and they couldn't get out).

Jay doesn't shy away from the darker stuff:

- Insulin Coma Therapy: Putting people into a coma to "reset" their brain.

- Barbiturates: Basically "warehousing" people in a chemical fog.

- Lobotomies: A quick surgical fix that often left people as shells of themselves.

It sounds barbaric now, but at the time, these doctors thought they were being "progressive." They were trying to get people out of the overcrowded, crumbling Victorian asylums. It’s a reminder that what we consider "cutting-edge" today might look like a nightmare in fifty years.

It’s Not Just "Over There" Anymore

Jay ends the book with a bit of a gut-punch. He argues that in the "post-asylum" world, madness hasn't disappeared; it's just been distributed.

✨ Don't miss: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

We closed the big hospitals in the 60s and 70s—a movement called deinstitutionalization. The idea was that people would live in the community and get support there. But the funding never really followed. Now, instead of one big Bedlam, we have thousands of smaller ones: prison cells, homeless encampments, and lonely apartments where people are managed by a cocktail of pills.

He mentions a place called Geel in Belgium, which is the total opposite of Bedlam. Since the 13th century, the townspeople there have taken mentally ill "boarders" into their own homes. No locks. No uniforms. Just living together. It’s the one model that seems to actually work, yet it's the one we've almost never tried to copy in the West.

What You Can Actually Do With This Information

Reading This Way Madness Lies isn't just a history lesson; it's a perspective shift. If you're interested in how we think about mental health today, here are some ways to apply Jay's insights:

- Question the "Progress" Narrative: Don't assume that because we have apps and modern meds, we've "solved" the problem. Every era has its own blind spots.

- Look for the Human, Not the Diagnosis: Jay spends a lot of time on patient art and diaries for a reason. A diagnosis tells you what a person has, but their stories tell you who they are.

- Support Community-Based Care: The history of the asylum shows that isolation almost always leads to abuse. The more integrated mental health care is into our actual lives—not tucked away in a clinic—the better.

- Visit the Bethlem Museum of the Mind: If you’re ever in London, go see the archives Jay worked with. Seeing the "Air Loom" drawings or Richard Dadd's paintings in person is a completely different experience than seeing them on a screen.

The story of madness isn't over. As Jay says, the world has basically become a "great Bedlam." We’re all trying to figure out how to live with our own minds, and looking back at where we've been is the only way to make sure we don't keep walking in circles.