You’ve heard it in Sunday school. You’ve heard it at political rallies. You might even remember it from a Barney episode or a Bruce Springsteen concert. It’s one of those songs that feels like it’s just always existed, like it was plucked out of the air by some anonymous ancestor and handed down through the generations. But "This Little Light of Mine" isn't just a cute nursery rhyme or a simple campfire tune. It’s actually a song with a bit of an identity crisis, a complicated paper trail, and a massive legacy that basically changed the course of American history.

Most people assume it’s an old "Negro Spiritual" from the days of slavery. That’s the most common misconception you'll find on the internet. Honestly, it’s not true. While it carries that spirit, the song was actually written in the 1920s by a white teacher named Harry Dixon Loes. He was a moody, prolific composer who reportedly wrote thousands of songs, but this one stuck. He wrote it for children. He wanted something catchy. He succeeded.

The Surprising Origins of This Little Light of Mine

Harry Dixon Loes was a man deeply embedded in the moody world of mood music and gospel. He studied at the Moody Bible Institute. He wasn't trying to write a protest anthem. He was trying to give kids a way to internalize a verse from the Bible—specifically Matthew 5:16, which talks about letting your light shine before others.

It’s weirdly fascinating how a song meant for a quiet classroom in the Midwest ended up on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement. The transition didn't happen overnight. It happened because the song is fundamentally "sticky." The melody is simple. The rhythm is relentless. You can clap to it. You can stomp to it. And most importantly, you can change the words.

- The Verse Factor: The song is built on a "call and response" structure, which is a staple of African American musical tradition. This is why so many people mistakenly categorize it as a traditional spiritual.

- The Adaptability: You can sing "Everywhere I go," or "In my neighborhood," or "All over the world." It’s a modular song.

By the time the 1950s rolled around, the song had been absorbed into the Black church. It was being rearranged. It was getting "soul." It was no longer a polite ditty for children; it was becoming a roar.

From Pews to Protests: The 1960s Transformation

If you want to understand why this little light of mine matters, you have to look at the Freedom Singers. During the 1960s, music wasn't just entertainment. It was a weapon. It was a tool for survival. When you're facing down fire hoses or police dogs, you don't sing something complicated. You sing something that reminds you of your own worth.

Zilphia Horton, a massive figure at the Highlander Folk School, played a huge role in taking songs like this and turning them into "Freedom Songs." She taught them to organizers. Those organizers took them to the South.

Think about the lyrics for a second. "Hide it under a bushel? No!" That’s not just about a candle anymore. In 1963 Mississippi, that was about refusing to be silenced. It was about standing up to the Jim Crow laws. It was about the audacity of existing out loud.

I spoke with a music historian once who pointed out that the song’s power comes from the word "Little." It’s humble. It’s not "This Giant Searchlight of Mine." It acknowledges that the individual might feel small, but that small light is still blinding when everyone holds it up together.

The Myth of the "Underground Railroad" Code

There is a popular theory floating around social media—you’ve probably seen the TikToks—claiming that the song was a secret code for the Underground Railroad. People say the "light" referred to a lantern in a window signaling a safe house.

It's a beautiful story. It's also almost certainly fake.

As mentioned earlier, the song was copyrighted in the 1920s. Harriet Tubman died in 1913. The dates just don't work. While it’s true that many spirituals like "Follow the Drinking Gourd" or "Wade in the Water" contained coded instructions for escaping slaves, "This Little Light of Mine" doesn't fit that timeline.

Does that make it less powerful? Not really. But it’s important to give credit to the actual era where it did its heaviest lifting. Its "warrior" status was earned in the 60s, not the 1860s.

Famous Versions You Need to Hear

You haven't really heard the song until you've heard a few specific versions. Each one tells a different story.

- Odetta: She was the "Queen of American Folk Music." Her version is percussive and heavy. It feels like a march. When she sang it at the March on Washington, it wasn't a song—it was a demand.

- Sister Rosetta Tharpe: She played it on an electric guitar. She brought the rock and roll. It’s wild, energetic, and slightly dangerous.

- Bruce Springsteen: The Boss turned it into a massive, gospel-rock stadium anthem. It shows how the song can scale from a single voice to 80,000 people.

- Fannie Lou Hamer: Her recordings are raw. You can hear the grit and the exhaustion in her voice. For her, the "light" was the right to vote.

Why We Still Sing It in 2026

It’s easy to dismiss it as a cliché. It’s been used in commercials for orange juice and insurance. But the song persists because it addresses a fundamental human need: the desire to be seen.

👉 See also: Sheriff Chris Mannix: Why This Hateful Eight Character Is Actually the Movie’s Soul

In a world that feels increasingly fragmented, the song acts as a bridge. It’s one of the few pieces of music that a 5-year-old and an 80-year-old both know by heart. It’s universal. It’s also incredibly easy to learn in about thirty seconds, which is why it shows up at every protest from environmental rallies to human rights marches.

The song is also a masterclass in psychological resilience. It uses "I" statements. "I'm gonna let it shine." This is personal accountability set to music. It's an internal pep talk that happens to have a catchy hook.

The Technical Side: Musicology and Structure

Musically, the song usually sits in a major key, which is why it feels "happy." But if you slow it down and move it to a minor key—which some blues artists have done—it becomes haunting.

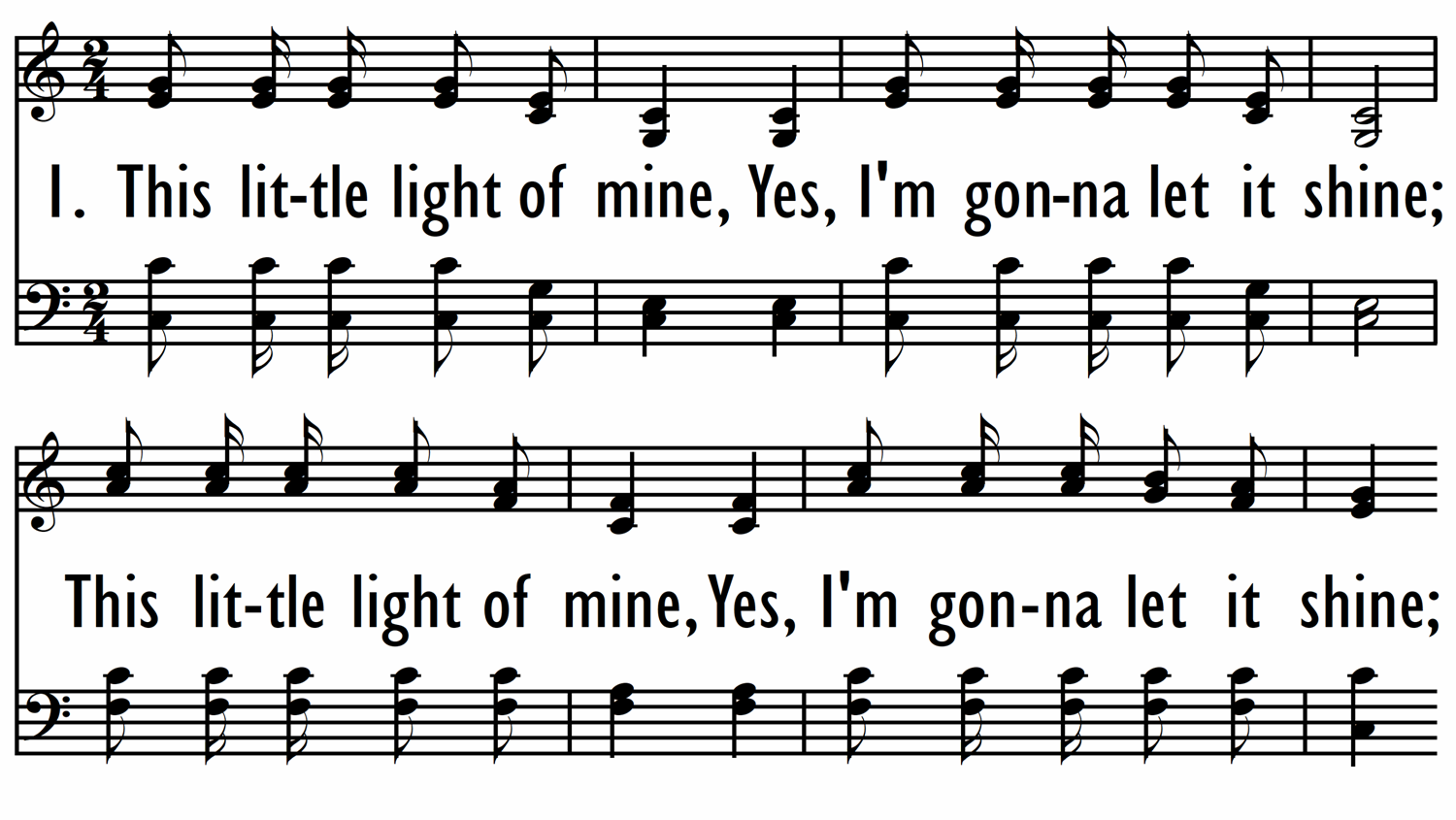

The standard time signature is 4/4. Simple. Reliable. Most versions use a basic I-IV-I-V chord progression. This is the "Three Chords and the Truth" philosophy. You don't need a music degree to play it, which is exactly why it spread so fast through rural communities and urban centers alike.

Actionable Takeaways for Musicians and Educators

If you’re planning on performing or teaching this little light of mine, don't treat it like a museum piece. It’s a living document.

✨ Don't miss: Delroy Lindo Movies and TV Shows: Why He’s the Most Underrated Legend in Hollywood

- Respect the History: Acknowledge its roots in both the gospel tradition and the Civil Rights Movement. Don't just call it a "kids' song."

- Encourage Improvisation: The song was built for new verses. If you're using it in a modern context, ask people what their "light" is today. Is it kindness? Is it truth? Is it justice?

- Watch the Tempo: Don't let it get too "sing-songy." The best versions have a bit of a "swing" to them. It should feel like it's moving forward, not just sitting there.

- Check Your Sources: If you're writing a program or a blog post, avoid the "Underground Railroad" myth. Stick to the documented history of Harry Dixon Loes and the Freedom Singers. Truth is usually more interesting than the legend anyway.

The song is basically a survival kit in a melody. It’s been through the Great Depression, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and every social upheaval since. It’s not going anywhere. Whether you're singing it in a cathedral or hummng it in your kitchen, you're tapping into a century of collective hope.

To truly appreciate the depth of this anthem, listen to the 1960s field recordings from the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). You'll hear the clapping, the off-key shouting, and the sheer bravery of people who had everything to lose. That's the real song. Everything else is just a cover.

Next Steps:

Go find the 1963 recording of the Freedom Singers at the Newport Folk Festival. Listen to the way they trade off the lead vocals. Then, try to find a version by a local community choir. Notice the difference in energy. The song is a mirror; it sounds like the people who are singing it. Use this as a jumping-off point to explore other "Freedom Songs" like "We Shall Not Be Moved" or "Oh, Freedom." Understanding the context of one makes the others much more meaningful.