You know the feeling. It’s that irrepressible itch to tap your toes when a specific four-four beat kicks in. Maybe you first heard it in a dusty church basement with a tambourine rattling in the background, or perhaps you saw a grainy black-and-white clip of Civil Rights protestors singing it while facing down fire hoses. This little light of mine christian song isn't just a Sunday School staple; it's a piece of sonic DNA that has woven itself into the very fabric of American history.

It’s deceptively simple.

Honestly, the lyrics are so straightforward a toddler can memorize them in three minutes. Yet, that simplicity is exactly why it survived the transition from rural churches to the front lines of social revolution. Most people assume it’s a Negro Spiritual passed down from the days of slavery. That’s a common mistake, but it’s actually not quite right.

The Surprising Origin of This Little Light of Mine

We usually credit Harry Dixon Loes for the version we know today. He was a teacher and composer at the Moody Bible Institute in the 1920s. Think about that for a second. While the song feels like it bubbled up from the red clay of the South, its formal notation came from a guy in Chicago.

Loes wrote it as a children’s chorus. He wanted something catchy, something that would stick in a kid's brain like a stubborn burr. He succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. But even though Loes gets the credit in many hymnals, the song has deep, undeniable roots in African American oral traditions. It’s a hybrid. It’s a bridge between formal hymnody and the raw, soulful expression of the Black church.

The song draws its power from the Bible, specifically Matthew 5:16. "Let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven." That’s the core. It’s about personal agency. It’s about the idea that even if you feel small, you’ve got something inside that can push back the dark.

Why the "Children's Song" Label is Misleading

If you stop at the "I'm gonna let it shine" part, you're missing the grit. In the 1950s and 60s, the this little light of mine christian song underwent a radical transformation. It stopped being just about a candle on a hill and started being about resistance.

Fannie Lou Hamer, the legendary civil rights activist, used this song as a weapon. She didn't sing it like a nursery rhyme. When she sang "All in my house, I'm gonna let it shine," she wasn't talking about a literal house. She was talking about her community, her state, and her right to vote. She sang it with a growl and a conviction that made the simple melody sound like a thunderclap.

Musicologists like Bernice Johnson Reagon have pointed out that during the movement, the "light" became a metaphor for the truth of one's own humanity. If the system tells you that you are nothing, singing that you have a "light" is a revolutionary act. It’s a refusal to be extinguished.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

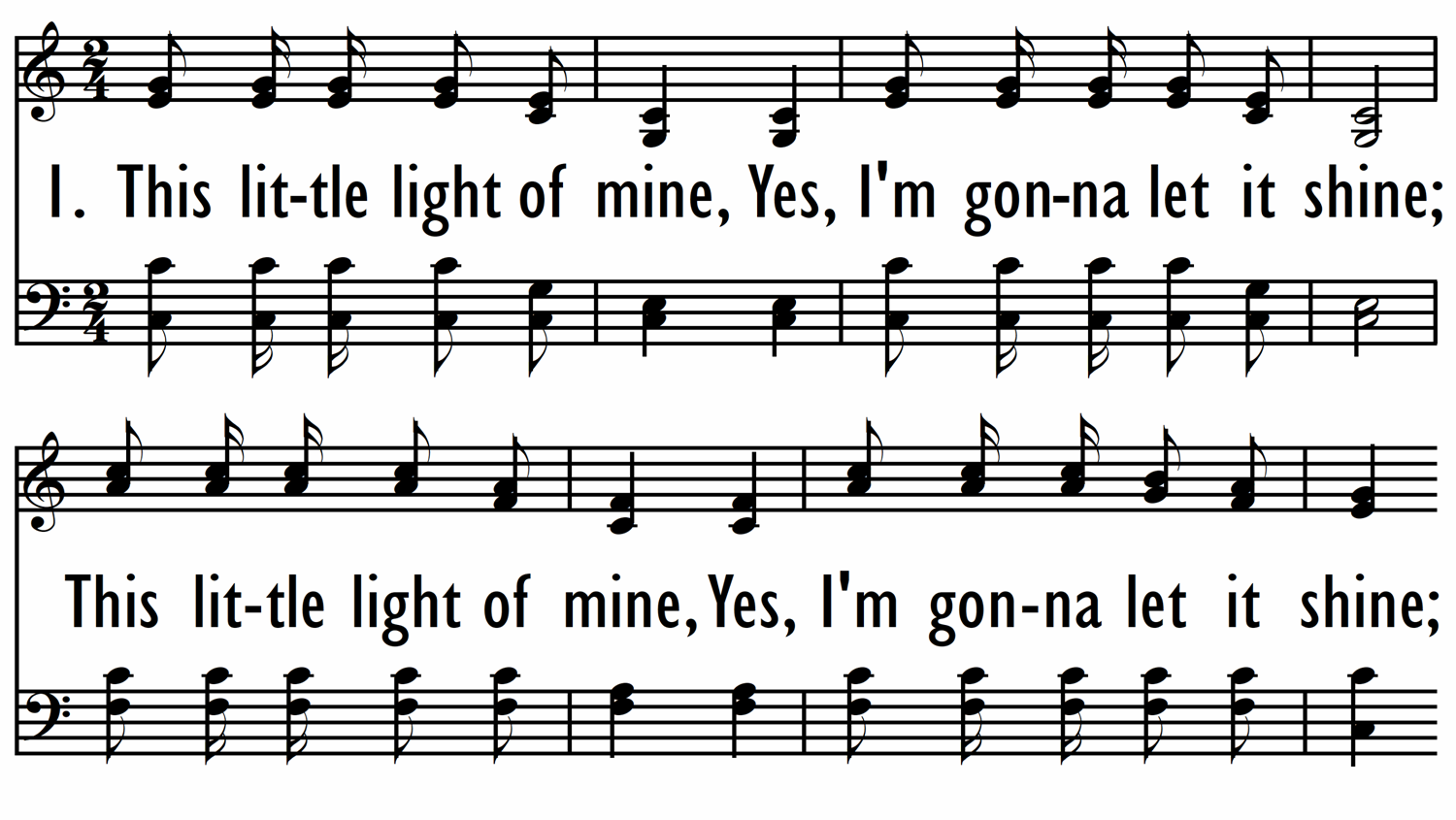

How the Song Actually Works (Musically)

It’s all about the "call and response."

In many traditional performances, a leader will call out a location or a situation—"In the jailhouse!"—and the congregation roars back, "I'm gonna let it shine!" This structure makes the song infinitely adaptable. You can make it about your neighborhood, your struggles, or your specific joys.

Musically, it’s often played in a major key, which gives it that "happy" vibe. But if you listen to the way Odetta or Sam Cooke sang it, they often added blue notes. They bent the pitches. They turned a simple melody into something complex and yearning.

- Rhythm: It usually sits in a steady, driving 4/4 time.

- Melody: The intervals are easy to reach, making it perfect for group singing.

- Structure: AAAA or AABA, depending on the arrangement. It’s repetitive for a reason. Repetition leads to a trance-like state of focus.

The Great Performance Debate: Folk vs. Gospel

There’s this weird tension between how folk singers and gospel singers handle the track. In the folk world—think Pete Seeger or The Seekers—the song is often treated as a polite anthem of peace. It’s clean. It’s acoustic. It’s very... polite.

Then you go to a Black gospel service.

There, the this little light of mine christian song is a powerhouse. There are Hammond B3 organs screaming in the background. There are drum kits. There are vocal runs that defy physics. In this context, the song isn't a suggestion; it’s an evidentiary statement. It’s a testimony.

Misconceptions You Probably Believe

Let's clear the air on a few things.

First, as mentioned before, it isn't a traditional spiritual in the sense that "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" is. Spirituals typically pre-date the Civil War and were born out of the experience of enslaved people. This song appeared much later, around the 1920s.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Second, it’s not just a "Christian" song anymore. While its origins are deeply rooted in the faith, it has become a secular anthem for human rights. It’s been sung by people of all faiths (and no faith) in protest lines from Selma to Soweto. It has become a universal shorthand for "I will not be silenced."

Third, the verse about "Hide it under a bushel? No!" is a direct reference to the Parable of the Lamp. A "bushel" was a large basket used for measuring grain. Putting a lamp under it wouldn't just hide the light; it would probably smother the flame from lack of oxygen. The song is basically saying that if you hide who you are or what you believe, you’ll eventually die inside.

Why We Still Sing It in 2026

You’d think a song this old would have faded into the background by now. We have high-def streaming and complex pop hits, yet this three-chord wonder persists. Why?

Honestly, it’s because the world still feels dark sometimes.

Whether it's political division, personal loss, or just the general weight of being alive, people need a way to reclaim their power. The song provides a low barrier to entry. You don’t need to be a trained vocalist. You don't even need to be particularly religious to feel the tug of the message.

It’s also incredibly versatile for modern media. You’ve heard it in movies, commercials, and TV shows. Bruce Springsteen has covered it. So has Lizzo. It can be a dirge or a dance track.

The Cultural Impact of the 1960s Version

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, music was the glue that held the movement together. When activists were thrown into jail in Parchman, Mississippi, they didn't have weapons. They had songs.

They would sing this little light of mine christian song through the bars. It was a psychological tactic. It showed the guards that their spirits weren't broken. If you can still sing about your "light" while sitting in a damp cell, you've already won. The song became a shield.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Practical Ways to Use the Song Today

If you're a worship leader, a teacher, or just someone who likes music, there are better ways to approach this song than just singing the standard "Sunday School" version.

- Change the Tempo: Try singing it as a slow, soulful ballad. It changes the meaning entirely. It becomes a prayer of desperation rather than a happy tune.

- Add Your Own Verses: The song is built for improvisation. "When I'm at the office," "When the news is bad," "Even when I'm tired." Make it personal.

- Teach the History: Don't just sing it. Tell the story of Fannie Lou Hamer. Explain the Moody Bible Institute connection. Context gives the words weight.

Actually, the best way to experience the song is to find a recording by the Selma Inter-Religious Project or the SNCC Freedom Singers. Listen to the way their voices crack. Listen to the stomping of feet. That is where the "real" song lives.

Moving Forward with the Music

Music moves us because it bypasses the logical brain and hits the nervous system. This little light of mine christian song does this better than almost any other piece of American music. It’s a reminder that we are responsible for our own internal glow.

Don't let the simplicity fool you into thinking it's shallow. It’s a deep well.

Next time you hear those opening notes, don't just hum along. Think about the people who sang it when their lives were literally on the line. Think about the "light" you're trying to keep lit in your own life.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Listen to the versions by Odetta and Fannie Lou Hamer to understand the song’s transition from a children's tune to a protest anthem.

- Incorporate "Call and Response" into your next group gathering or classroom setting to experience the communal power of the structure.

- Research the "Parable of the Lamp" (Matthew 5:14-16) to see the direct biblical inspiration for the lyrics and how they've been interpreted over the last century.

- Try re-arranging the song in a minor key if you're a musician; you'll find it takes on a haunting, resilient quality that fits more somber occasions.

The song isn't just a relic of the past. It's a tool for the present. Use it.