Ever feel like you’re playing a never-ending game of Whac-A-Mole? You fix a problem in your budget, and suddenly your marketing performance drops. You hire more people to speed up a project, but somehow the work actually slows down. It’s frustrating. Most of us are taught to look at the world as a series of straight lines—A causes B, and B causes C. But the world doesn't really work that way. It's messy. It's a web. This is exactly why thinking in systems: a primer on how things actually connect is more than just a mental exercise; it’s a survival skill for the modern world.

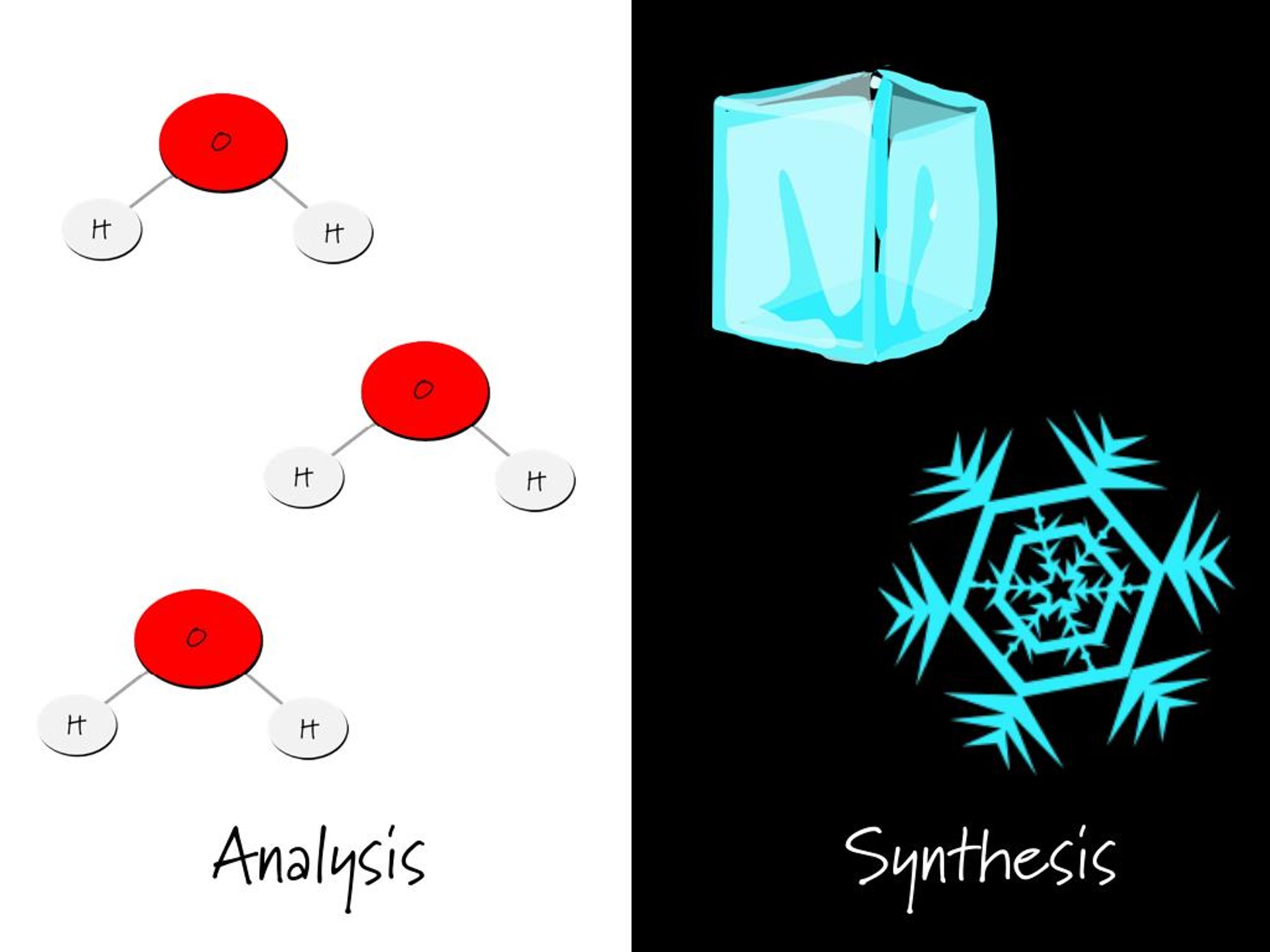

Most people look at a "problem" as a single event. They see a forest fire and think about the match. They see a stock market crash and blame a single tweet. Systems thinkers look at the forest, the wind patterns, the historical buildup of dry brush, and the regulatory environment that discouraged controlled burns. They see the structure. Donella Meadows, one of the pioneers of this field, basically argued that the "system" is more than the sum of its parts. If you take a collection of parts—say, a pile of sand—and remove some, you just have a smaller pile of sand. But if you take a system—like a digestive tract or a business—and remove a part, the whole thing changes or dies.

Why We Get Systems So Wrong

We’re wired for snapshots. Evolution favored the human who could see a lion and run, not the one who sat around wondering about the ecological impact of apex predator decline on local grasslands. Because of this, we tend to focus on "events." An event is just a single data point. If you only react to events, you’re always playing catch-up.

You've probably heard of the "Cobra Effect." It’s a classic systems failure. During British rule in India, the government was worried about the number of venomous cobras in Delhi. Their solution? Offer a bounty for every dead cobra. It seemed logical. Linear. A (Bounty) leads to B (Fewer Cobras). But people are smart. They started breeding cobras in their backyards to claim the reward. When the government realized this and scrapped the program, the breeders released their now-worthless snakes into the wild. Result? Way more cobras than when they started. That’s a "feedback loop" in action, and if you aren't looking for them, they will bite you.

Stocks, Flows, and the Bathtub Analogy

To get a grip on thinking in systems: a primer for your own life, you have to understand three basic things: elements, interconnections, and a purpose. The easiest way to visualize how a system changes over time is the bathtub model.

Think of a bathtub. The water in the tub is the stock. This is the memory of the system—the amount of stuff that has accumulated over time. It could be the money in your bank account, the inventory in a warehouse, or the level of trust in a relationship.

💡 You might also like: UPS Cincinnati Gest Street Hub: What Most People Get Wrong About This Logistics Powerhouse

The flows are the faucet and the drain. The faucet is the "inflow" (your paycheck, new shipments, or kind words). The drain is the "outflow" (rent, sales, or arguments).

Here’s where it gets interesting: the stock only changes if the flows are out of balance. You can't just wish for more "stock" without looking at the rate of the flows. Many businesses fail because they focus entirely on the "inflow" of new customers while ignoring a massive "outflow" of existing ones leaving through a leaky drain. They’re pumping the faucet while the plug is pulled out. It’s exhausting and eventually, the tub stays empty.

The Power of Feedback Loops

Systems are kept in check—or sent spiraling out of control—by feedback loops. There are really only two kinds you need to care about.

- Balancing Loops: These are the "stability" agents. Think of a thermostat. When the room gets too cold, the heater kicks on. When it hits the target temp, it shuts off. It seeks an equilibrium. In your body, sweating is a balancing loop to keep you from overheating.

- Reinforcing Loops: These are the "engines" of growth or decay. The more you have, the more you get. Compound interest is the gold standard here. But it works both ways. A "death spiral" in a company—where low morale leads to bad service, which leads to fewer customers, which leads to budget cuts, which leads to even lower morale—is a reinforcing loop.

Most of the time, we try to "fix" a reinforcing loop by pushing harder against it. But systems thinkers know that the most effective way to change a system is often to find the "leverage point."

Finding the Leverage Points

Jay Forrester, a professor at MIT and the father of system dynamics, noticed something weird: often, the most obvious "solution" to a problem actually makes it worse. This is "counterintuitive behavior."

Take traffic congestion. The "obvious" fix is to build more lanes. But when you build more lanes, you make driving more attractive. More people decide to drive instead of taking the bus. Pretty soon, the new lanes are just as clogged as the old ones. This is called induced demand. To fix the traffic system, you might need to change the "goal" of the system—moving people, not cars—or introduce a "balancing loop" like congestion pricing.

Leverage points are places within a complex system where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything. Honestly, they’re usually not where you think they are.

- Numbers and Constants: Changing the tax rate or the minimum wage. This is where we spend 90% of our time arguing, but it's actually the least effective way to change a system.

- The Length of Delays: If you get immediate feedback on your actions, you change your behavior. Imagine if your shower took 10 minutes to change temperature after you turned the knob. You'd constantly be scalding yourself or freezing. Reducing delays in information can transform a business.

- The Goals of the System: This is a high-leverage point. If a company’s goal is "maximize quarterly profit," the employees will behave one way. If the goal is "become the most trusted brand in the world," they will behave entirely differently, even with the same staff.

- The Paradigm: This is the highest leverage point. This is the mindset out of which the system arises. If you believe that nature is a resource to be exploited, you build an extractive economy. If you believe nature is a biological foundation for life, you build a regenerative one.

Real-World Systems: The Case of the 1970s Fuel Crisis

In the early 70s, the world saw a massive shock in oil prices. To a linear thinker, the problem was "not enough oil." The solution? Drill more. But systems thinkers looked at the "energy intensity" of the economy. Amory Lovins, an expert in the field, argued that we didn't have an energy supply problem; we had an efficiency problem.

By looking at the system of how we used energy—poorly insulated houses, gas-guzzling cars—we found leverage. Between 1977 and 1985, the US economy grew by 27%, but oil use actually fell by 17%. We didn't just find more oil; we changed the system's relationship with it.

✨ Don't miss: John Mallory: What Most People Get Wrong About Goldman’s Wealth Chief

Common Traps and How to Avoid Them

If you're starting to use thinking in systems: a primer for your own decision-making, watch out for these "system archetypes." They are recurring patterns that trip people up.

- Policy Resistance: This happens when different actors in a system have different goals. If the government tries to keep food prices low for the poor, but that makes it unprofitable for farmers to grow food, the farmers stop growing it. The result is a shortage. The system "resists" the policy because the underlying incentives weren't addressed.

- Shifting the Burden: This is the "addiction" loop. You have a problem, and instead of fixing the root cause, you apply a "symptomatic fix" that makes the problem go away temporarily. But the symptomatic fix has a side effect: it weakens the system's ability to fix itself. Think of a company that uses consultants to solve every internal conflict instead of teaching their managers how to lead. The managers get worse at leading, so they need more consultants.

- Success to the Successful: This is the "rich get richer" phenomenon. If two people start with slightly different resources, the one with more resources has a better chance of winning more, which gives them even more resources. Without a "balancing loop" (like progressive taxes or anti-trust laws), the system eventually collapses because one player has everything and the game stops.

How to Start Thinking in Systems Today

You don't need a PhD in dynamics to start doing this. It's really about slowing down and asking different questions.

First, stop looking for "villains." In a poorly designed system, even "good" people will produce "bad" results. If you find yourself blaming an individual for a recurring problem, you’re probably missing the systemic structure that’s pushing them to act that way.

Second, look for the "delays." Most problems have a lag time between the cause and the effect. If you eat a donut, you don't instantly gain weight. If you start a marketing campaign, you don't instantly get sales. When we ignore delays, we tend to "over-correct," which creates wild swings in the system.

Third, draw it out. You don't need fancy software. Just grab a piece of paper. Draw your "stock" (the thing you want more of). Draw the "flows" (what increases or decreases it). Then, try to find the "feedback loops." What happens when the stock gets too high? What happens when it gets too low?

🔗 Read more: US Stock Market is Open Today: What You Need to Know Before Monday’s Big Break

Actionable Next Steps

- Identify a recurring problem in your work or life. Not a one-time fluke, but something that keeps happening every few months.

- Map the "Stocks": What is accumulating or depleting? (e.g., Your energy levels, your company's cash reserves, your team's morale).

- Identify the "Flows": What specifically adds to that stock? What drains it?

- Look for the Delay: Is there a gap between when you pull a lever and when you see a result? If so, stop pulling the lever so hard. Give the system time to react.

- Audit the Incentives: Ask, "What is the goal of the people in this system?" Often, people are doing exactly what they are being incentivized to do, even if it contradicts the "official" goal of the organization.

- Experiment at the Margins: Don't try to overhaul the whole system at once. Change one "flow" or one "feedback loop" and watch what happens for a set period.

Systems are inherently complex, and they rarely behave exactly how we expect. But by shifting from a "snapshot" view to a "movie" view, you stop reacting to the world and start participating in it. It's about seeing the dance, not just the dancers. This isn't just about being right; it's about being effective in a world that is more interconnected than ever before.