You’ve probably heard it in a drafty country church or maybe during a particularly somber scene in a movie. The melody is haunting. But it’s the words that really stick. There is a fountain with lyrics that feel almost too visceral for modern ears—talk of veins, blood, and losing "all their guilty stains." It sounds intense because it is.

William Cowper didn't write this in a vacuum of "peace and love." He wrote it from the depths of a psychological breakdown. Honestly, when you realize the guy who penned these famous lines spent a significant portion of his life convinced he was damned, the song takes on a whole different energy. It’s not just a religious ritual; it’s a survival scream.

People search for these lyrics today because they offer a brand of raw honesty that a lot of contemporary music avoids. There’s no sugarcoating here. We’re talking about a 250-year-old poem that refuses to go away, even in a digital world that usually prefers things a bit more sanitized.

The Man Behind the Fountain: William Cowper’s Dark Reality

To understand why there is a fountain with lyrics so focused on cleansing, you have to look at Cowper himself. Born in 1731, Cowper was a mess. Not a "bad person" mess, but a "struggling with severe clinical depression before we had a name for it" mess. He tried to end his life multiple times. He was institutionalized. He was a poet who found himself caught between a brilliant mind and a crushing sense of guilt.

Cowper lived in Olney, England, where he became close friends with John Newton. You know Newton—the former slave ship captain who had a massive change of heart and wrote "Amazing Grace." Newton was the loud, boisterous preacher; Cowper was the quiet, fragile poet. Together, they produced the Olney Hymns in 1779.

This wasn't some corporate collaboration. It was therapy.

Cowper wrote "There is a Fountain Filled with Blood" (the actual full title) during a period where he was desperately trying to believe that forgiveness was actually possible for someone as "broken" as he felt. When you read the stanza about the "dying thief" rejoicing to see that fountain, Cowper isn't just retelling a Bible story. He’s putting himself in the shoes of the thief. He’s asking, "If that guy got a second chance, is there hope for me?"

Analyzing the Imagery: Why the Blood?

Modern listeners sometimes recoil at the imagery. A fountain filled with blood? It’s a bit much for a Sunday morning, right?

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

But historically, this wasn't seen as "gory" in a horror-movie sense. It was based on a specific verse from the book of Zechariah (13:1) which mentions a fountain opened to cleanse sin. In the 18th century, this was high-level poetic symbolism. The idea was that the sacrifice was deep, permanent, and accessible to everyone—no matter how messy their life was.

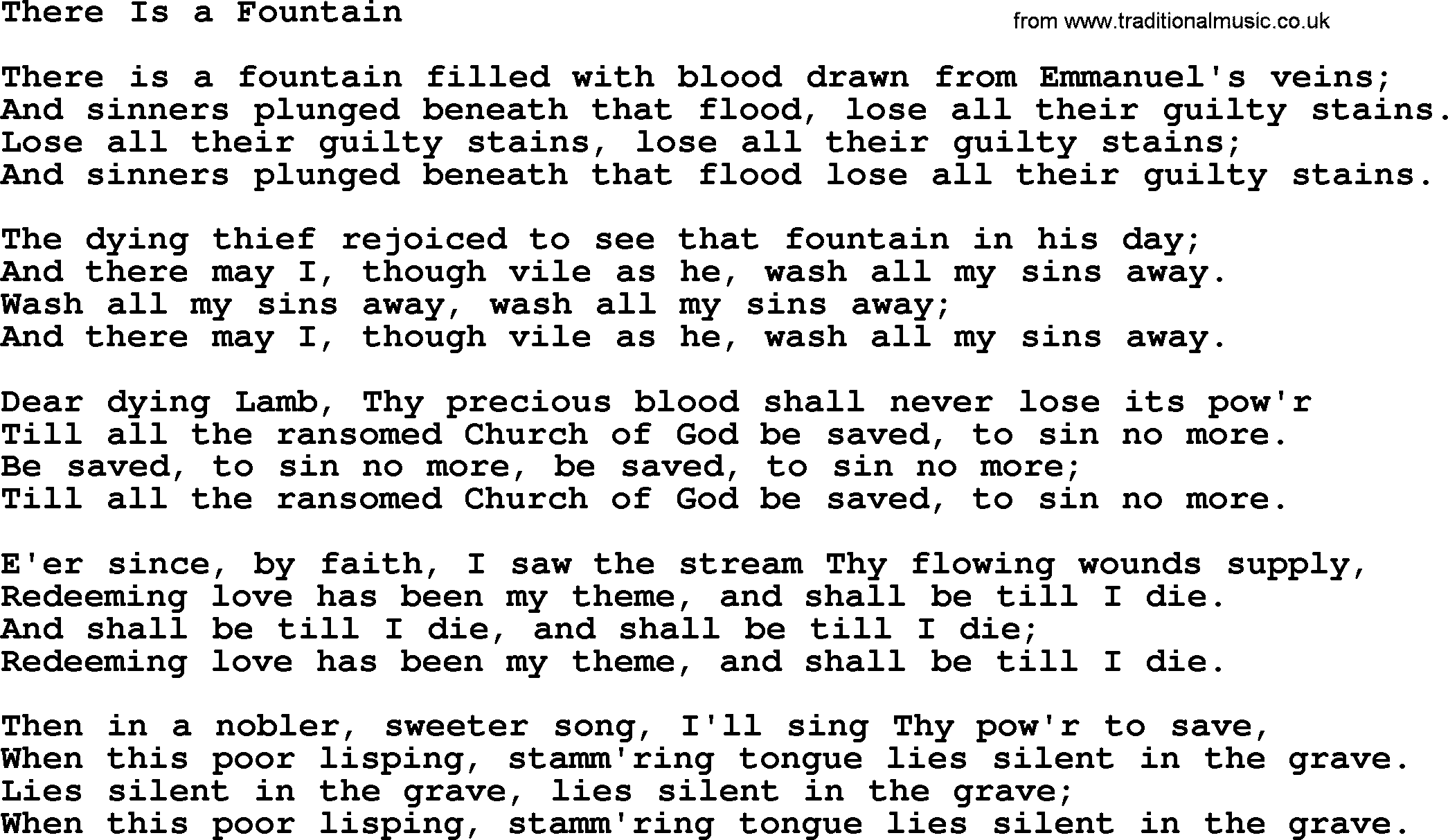

The lyrics vary slightly depending on which hymnal you’re holding, but the core remains:

- "There is a fountain filled with blood drawn from Emmanuel’s veins;"

- "And sinners plunged beneath that flood lose all their guilty stains."

The word "plunged" is doing a lot of heavy lifting there. It’s not a sprinkle. It’s not a light dusting of grace. It’s an immersive, total transformation. For someone like Cowper, who felt the weight of his "stains" every single day, that "plunge" represented the only possible way out of his mental prison.

Why the Lyrics Changed Over Time

If you’ve looked up there is a fountain with lyrics recently, you might have noticed some versions are softer. Some modern denominations have tried to swap out the "blood" imagery for words like "grace" or "love."

It rarely works.

The power of the song is in the grit. When you take the blood out of Cowper’s hymn, you take out the stakes. You take out the very thing that made it resonate with people living in poverty, people facing death, and people dealing with the kind of trauma Cowper faced.

Interestingly, the tune we usually associate with it today—an American folk melody called "Cleansing Fountain"—didn't come along until much later. The original 1779 version would have been sung to a much more formal, perhaps even dirge-like, English tune. The upbeat, almost rolling rhythm of the 19th-century American version turned it from a private poem of a suffering man into a communal anthem of hope.

💡 You might also like: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

It’s a weird juxtaposition. You have these heavy, crimson lyrics set to a tune that feels like it’s meant for a brisk walk through a field. But maybe that’s why it works. It balances the weight of the message with the lightness of the hope it's trying to convey.

The Cultural Footprint of the Fountain

This isn't just a church thing. The song has leaked into every corner of culture. You’ll find it in the works of Flannery O’Connor, who loved the "grotesque" but beautiful nature of the imagery. You’ll hear it in the background of Westerns. It’s been covered by everyone from Aretha Franklin to Johnny Cash and even Sufjan Stevens.

Why do artists keep coming back to it?

Because it’s "authentic." That’s a buzzword we use too much, but here it actually applies. There’s no irony in these lyrics. There’s no "well, it depends on your perspective." It’s a bold, unapologetic claim about the human condition and the possibility of being made new.

In a world where we spend a lot of time "curating" our images and pretending we’re fine, a song that starts by admitting we’re covered in "guilty stains" is actually kind of refreshing. It’s honest about the fact that being human is messy.

Notable Versions to Listen To:

- Selah: They do a version that leans into the traditional, soaring vocal style.

- Aretha Franklin: Her rendition is pure soul. She takes the "plunged" part literally—you can feel the immersion in her voice.

- The Petersens: A bluegrass take that highlights the American folk melody most of us recognize.

- Reawaken Hymns: Good for those who want a clearer, acoustic-led version to really hear the lyrics without the heavy organ.

Common Misconceptions About the Lyrics

A lot of people think the "fountain" is a literal place. It's not. It’s a metaphor for the crucifixion of Jesus, specifically the idea that his death provided a "wellspring" of forgiveness.

Another mistake? Thinking Cowper was a happy-go-lucky guy after he wrote it. He wasn't. He struggled until the day he died. He actually died believing he hadn't done enough to be saved, which is one of the great ironies of Christian history. The man who gave the world one of its most confident songs of assurance struggled to find that assurance for himself.

📖 Related: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

That nuance matters. It means the lyrics aren't "easy." They aren't cheap platitudes. They are the words of a man fighting for his life.

How to Use These Lyrics for Reflection

If you’re looking up there is a fountain with lyrics for a personal reason—maybe for a funeral, a study, or just because the song is stuck in your head—don't just skim the words.

Look at the third verse: "E’er since, by faith, I saw the stream Thy flowing wounds supply, Redeeming love has been my theme, and shall be till I die."

That’s a commitment. Cowper decided that since he "saw" this truth, he was going to make "redeeming love" his entire life’s work. Even when his brain told him he was worthless, his "theme" remained love. That’s a powerful psychological tool: choosing a theme for your life that is bigger than your current mood or mental state.

Actionable Takeaways for the Curious

If you want to dive deeper into this specific piece of musical and literary history, here is what you should actually do:

- Read the Olney Hymns Preface: John Newton wrote a preface to the collection where he talks about Cowper’s "shattered" state. It provides incredible context for the poems.

- Compare the Tunes: Find a recording of the hymn sung to the tune "Martyrdom" and then listen to it sung to "Cleansing Fountain." Notice how the "vibe" of the lyrics changes entirely based on the music.

- Study the Poetry: Cowper was a major influence on the Romantic poets (like Wordsworth and Coleridge). Look at his other poems, like "The Castaway," to see the darker side of the man who wrote the fountain song. It makes the hymn even more impressive.

- Check Your Hymnal: If you have an old family Bible or hymnal, look for the date of the version inside. Many 19th-century versions added a chorus that Cowper never wrote. Seeing the original five stanzas alone changes the pacing.

Cowper’s fountain isn't just a relic of the past. It’s a weirdly relevant piece of art for anyone who has ever felt like they needed a fresh start. It’s a reminder that even the most broken people can create things that offer healing to millions of others for centuries. That’s a legacy that’s hard to beat.

Next Steps for Exploration:

- Trace the Melody: Search for the "American Folk" origins of the "Cleansing Fountain" tune to see how it migrated from the UK to the US camp meetings.

- Literary Context: Read William Cowper's The Task to see his broader views on nature and humanity, which often contrast with the intense religious focus of his hymns.

- Historical Timeline: Map the publication of the Olney Hymns against the backdrop of the English Evangelical Revival to see how this song fueled a massive social movement.