Eleven miles off the coast of the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, something massive and mangled lies in the dark. It’s the wreck of RMS Lusitania, and honestly, it’s a mess. If you’re picturing the upright, majestic silhouette of the Titanic resting on the sandy floor, forget it. The Lusitania is a twisted, collapsing heap of steel that looks more like a discarded soda can than a luxury liner.

It’s been over a century. Since May 7, 1915, the ocean has been chewing on this ship, and it shows.

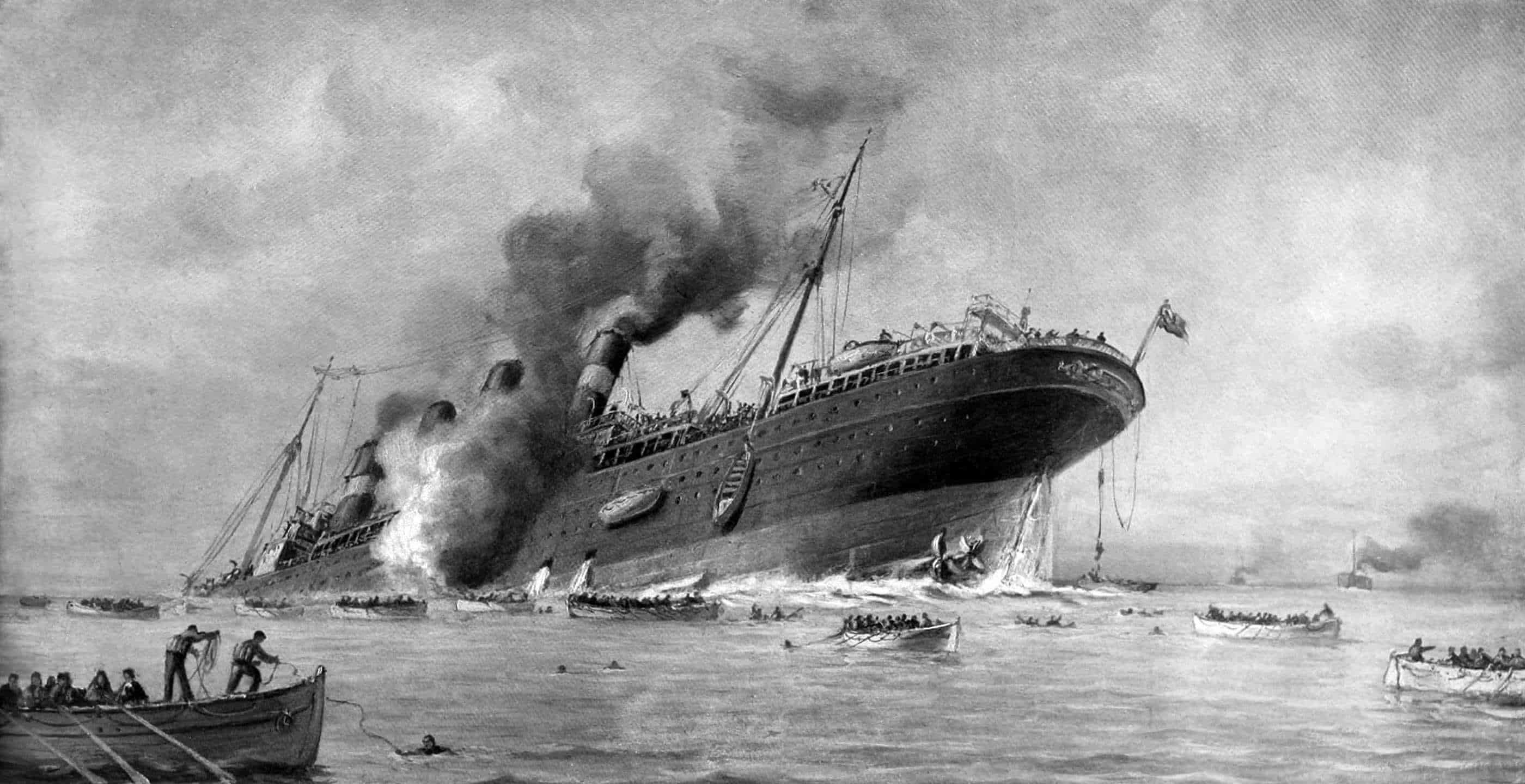

Most people think of the Lusitania as just a footnote to World War I—the "ship that got America into the war." But that’s a bit of a simplification, isn't it? The United States didn't actually declare war for another two years. The real story of the wreck is buried in the silt and the controversy over what was actually inside those cargo holds. When a German U-20 submarine fired a single torpedo, the ship sank in just 18 minutes. 18 minutes. Compare that to the Titanic’s two hours and forty minutes. It was a brutal, chaotic plunge that left the ship lying on its starboard side in roughly 300 feet of water.

Because it’s in relatively shallow water compared to other famous wrecks, you’d think we’d know every inch of it. We don't. The depth is actually a curse. It’s deep enough to be deadly for most divers, yet shallow enough that the ship was hammered by fishing nets, depth charges from the British Navy during WWII (who were practicing or perhaps trying to hide something), and the relentless pull of the tides.

What’s Actually Left of the Wreck of RMS Lusitania?

If you were to dive down there today—which is incredibly difficult because of the Irish government's strict heritage orders—you’d see a tragedy in slow motion. The hull is collapsing.

The ship hit the bottom hard. Because it was so long (787 feet) and the water was so shallow (300 feet), the bow actually struck the seabed while the stern was still poking out of the water. Imagine the stress on that steel frame. It basically buckled the moment it arrived. Robert Ballard, the guy who found the Titanic, explored the wreck of RMS Lusitania in 1993. He described it as looking like it had been through a "giant blender."

The superstructure has largely slid off the hull and turned into a debris field. You can still see the massive boilers, though. They are huge, haunting cylinders of iron that refuse to decay as fast as the rest of the ship. The four massive propellers were a major point of interest for decades, though three were salvaged back in the 1980s. One of them actually ended up being melted down into golf clubs, which feels a bit disrespectful, but that’s history for you.

The Mystery of the Second Explosion

This is the big one. The one that keeps historians up at night.

📖 Related: Philly to DC Amtrak: What Most People Get Wrong About the Northeast Corridor

When the torpedo hit, there was a small explosion. Totally expected. But then, seconds later, a massive, ship-shattering second blast occurred. German Captain Walther Schwieger noted it in his logbook. For years, the British government blamed coal dust or a ruptured steam line. But the "conspiracy" crowd—and a lot of serious researchers—point to the manifest. The Lusitania was carrying over 4 million rounds of .303 rifle ammunition.

Gregg Bemis, the American venture capitalist who owned the salvage rights to the wreck for years, spent much of his life trying to prove that the ship was a legitimate military target because of those munitions. He faced endless legal battles with the Irish state, which treats the wreck as a gravesite and a cultural treasure. He wanted to find the "smoking gun" in the holds, but the wreck is so collapsed that getting into the cargo areas is like trying to crawl through a house of cards.

Diving the Ghost: Why It's So Dangerous

You can't just rent a boat and go see the wreck of RMS Lusitania.

The Irish government issued an Underwater Heritage Order in 1995. You need a specific license to dive it. And even if you get the paperwork, the site is a nightmare. The visibility is usually terrible—often less than 10 feet. The currents are ripping. Then there’s the "ghost gear." Because the wreck is on a popular fishing ground, it is draped in miles of discarded heavy-duty fishing nets. If a diver gets snagged in those in the dark, 300 feet down, they aren't coming back up.

Over the years, several divers have been seriously injured or killed trying to document the site. It’s not a place for "adventure travel." It’s a graveyard. 1,198 people died when she went down.

Why the Condition is Deteriorating Fast

Unlike the Titanic, which is being eaten by Halomonas titanicae bacteria in the freezing, still depths, the Lusitania is being destroyed by physical force.

- The Tides: The Irish Sea is restless. The water moves the sand back and forth, effectively sandblasting the steel.

- The Depth Charges: During the 1940s and 50s, the Royal Navy reportedly used the wreck for target practice. They denied it for a long time, but sonar scans show craters around the hull that don't match torpedo damage.

- The Weight: The ship is lying on its side. Ships are built to be upright. The weight of the port side is crushing the starboard side into the silt.

Eventually, the wreck of RMS Lusitania will be nothing more than a rust stain on the ocean floor. Experts estimate that within the next 20 to 50 years, the hull will completely flatten.

👉 See also: Omaha to Las Vegas: How to Pull Off the Trip Without Overpaying or Losing Your Mind

The Human Element: Artifacts and Ethics

What do we do with what’s left? This is a massive debate in the maritime archaeology world.

Some people, like the late Gregg Bemis, believed we should recover as much as possible before it’s gone. They’ve pulled up the ship's bell, whistles, and thousands of personal items. These pieces end up in museums, like the one at the Old Head of Kinsale or the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool. They tell a story that a pile of rotting steel can't. They show the fine china, the children's shoes, the gold coins.

On the other side, many descendants of the victims think the site should be left entirely alone. They see any salvage as grave robbing. It’s a tough balance. If we leave it, the sea destroys the history. If we take it, we disturb the dead.

Honestly, it’s kinda heartbreaking. You have this pinnacle of Edwardian engineering—a ship that was once the fastest in the world—and now it’s just a maze of snagged nets and corroding rivets.

Misconceptions People Still Believe

One thing that drives historians crazy is the idea that the Lusitania was "set up" by Winston Churchill to bring the U.S. into the war. While it's true the British were desperate for American help, there is no hard evidence that they intentionally put the ship in the path of U-20. The ship was warned. The captain, William Turner, made some questionable choices—like not zig-zagging and staying too close to the coast—but he wasn't a murderer. He was a man who didn't believe a "civilized" nation would sink a passenger liner without warning. He was wrong.

Another myth? That there was a massive amount of gold on board. People love a treasure hunt. While there were certainly wealthy passengers with jewelry and cash, there wasn't a "secret bullion" shipment. The real "gold" was the secret cargo of war materials, which changed the legal status of the ship under international law.

How to Connect with the History Today

Since you can't realistically dive the wreck of RMS Lusitania, how do you actually "experience" it?

✨ Don't miss: North Shore Shrimp Trucks: Why Some Are Worth the Hour Drive and Others Aren't

The best way is to head to the Old Head of Kinsale in County Cork. There is a memorial garden there and a museum housed in an old signal tower. You can stand on the cliffs and look out at the exact spot where the smoke would have been visible on the horizon. It’s a haunting experience. You realize how close they were to safety. They were only miles from the harbor.

You can also look into the digital preservation projects. Several teams have used multi-beam sonar to create 3D maps of the wreck. These digital twins are probably the only way future generations will see the ship at all. They show the "glory" of the wreck in a way a muddy photograph never could.

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper (metaphorically) into the story of the Lusitania, here is how to do it right:

- Read the Right Books: Skip the conspiracy blogs. Start with Dead Wake by Erik Larson. It’s meticulously researched and reads like a thriller. It gives you the "human" side of the sinking that the wreckage can't.

- Visit the Museums: If you’re in the UK, go to Liverpool. The city was the home port of the Lusitania, and the museum there has an incredible collection of personal stories and artifacts.

- Explore the National Monuments Service (Ireland) Records: They have public records of the archaeological surveys. If you're a data nerd, looking at the sonar bathymetry is fascinating.

- Support Maritime Preservation: Organizations like the Nautical Archaeology Society often work on projects related to WWI shipwrecks. They are the ones fighting to keep these stories alive before the salt water wins.

The wreck of RMS Lusitania is more than just a pile of scrap metal. It’s a snapshot of the moment the world changed—the moment "total war" became a reality and the innocence of the 19th century finally died. It’s a grim, beautiful, and complicated piece of our shared history that is slowly fading into the Atlantic mud. We should pay attention to it while there’s still something left to see.

The ocean doesn't keep secrets forever; it just dissolves them. If you want to understand the 20th century, you have to understand what happened on that Friday in May, and what remains of the ship that tried to outrun a war.

The site remains a protected war grave. Respecting that status is the most important thing any researcher or visitor can do. History isn't just about what we can take from the bottom; it's about what we remember on the surface. For the Lusitania, the memory is finally becoming clearer, even as the steel disappears.