It was supposed to be a challenge. In September 2005, Blizzard Entertainment released a patch for World of Warcraft that introduced Zul’Gurub, a high-level raid featuring a boss named Hakkar the Soulflayer. Hakkar had a trick up his sleeve: a debuff called Corrupted Blood. It was a nasty, life-draining infection that jumped from player to player. If you were a level 60 warrior with thousands of health points, it was an annoyance. If you were a level 10 mage just trying to sell some linen cloth in Ironforge, it was an instant death sentence.

Basically, the developers intended for the plague to stay inside the raid instance. They didn't account for the pets.

When hunters dismissed their infected pets inside the raid and summoned them back in the crowded streets of Ironforge or Orgrimmar, they brought the virus with them. What followed wasn't just a glitch. It was a total breakdown of social order that caught the attention of the CDC and real-world epidemiologists. People still talk about the World of Warcraft pandemic today, not just as a gaming meme, but as a terrifyingly accurate model of human behavior during a crisis.

How the Corrupted Blood Outbreak Actually Started

The mechanics were simple. Corrupted Blood dealt direct damage over time and was highly contagious. Because the major cities in WoW are high-traffic hubs where players go to trade, bank, and chat, the density was perfect for a "superspreader" event. You'd log in, stand near the mailbox for ten seconds, and suddenly your character would keel over.

Blizzard tried to implement "quarantines." It didn't work. Honestly, the player response was the most fascinating part of the whole mess. Some players with healing abilities set up makeshift field hospitals at the city gates, desperately casting spells to keep lower-level players alive. Others, sensing the end was near, retreated to the mountains or deserted islands to wait it out.

But then there were the others.

🔗 Read more: First Name in Country Crossword: Why These Clues Trip You Up

A small but significant portion of the population became "griefers." They realized they could weaponize the plague. These players would intentionally get infected and run into low-level starting zones like Goldshire just to see how many people they could kill. This "malicious intent" factor is something that standard mathematical models of disease often overlook. Real viruses don't have a conscious mind, but the people carrying them do.

The Role of NPCs as Asymptomatic Carriers

One of the biggest reasons the World of Warcraft pandemic wouldn't die was the NPCs (Non-Player Characters). Shopkeepers, quest givers, and bank tellers could contract the virus, but because they have massive health pools or "essential" status, they didn't die. They became permanent reservoirs.

Think about that for a second.

You’d walk up to a vendor to buy some bread, and the vendor—who looked perfectly fine—would pass you a lethal dose of Corrupted Blood. In the real world, we call this being an asymptomatic carrier. It’s exactly why the outbreak was so hard to contain. Blizzard eventually had to hard-reset the servers and apply a hotfix to make the debuff non-contagious, but by then, the data was already being collected by scientists like Dr. Nina Fefferman and Dr. Eric Lofgren.

Why Scientists Still Study a 20-Year-Old Game Bug

In 2007, Fefferman and Lofgren published a paper in The Lancet Infectious Diseases. They argued that virtual worlds provide a "petri dish" for studying things that are impossible or unethical to study in real life. You can't just release a virus in a city to see if people will listen to a quarantine order. But in World of Warcraft, you could watch it happen in real-time.

💡 You might also like: The Dawn of the Brave Story Most Players Miss

The behavior of players during the World of Warcraft pandemic mirrored real-world reactions to a frightening degree.

- Curiosity seekers: People heard there was a "death plague" in Ironforge and traveled there specifically to see the piles of skeletons, inadvertently catching it and spreading it further.

- Distrust of authority: When Blizzard told players to stay away from the cities, many ignored the warning, thinking it was just "flavor text" or an annoying restriction on their gameplay.

- Panic and Flight: Once the death toll became apparent, massive migrations happened, which in a real-world scenario would have accelerated the spread to rural areas.

Dr. Fefferman later noted that the most valuable takeaway wasn't about the virus itself, but about the "human element." Most computer models assume people will act rationally or predictably. The WoW incident proved that people are chaotic. Some will help, some will hide, and some will actively try to burn the world down just for the "lulz."

Common Misconceptions About the Incident

A lot of people think Blizzard planned this as a "world event." They didn't. It was a massive oversight in the code. Another myth is that the plague wiped out the entire game population. While it was devastating in the cities, players who stayed in the wilderness were mostly fine. The "pandemic" was really a crisis of urbanization.

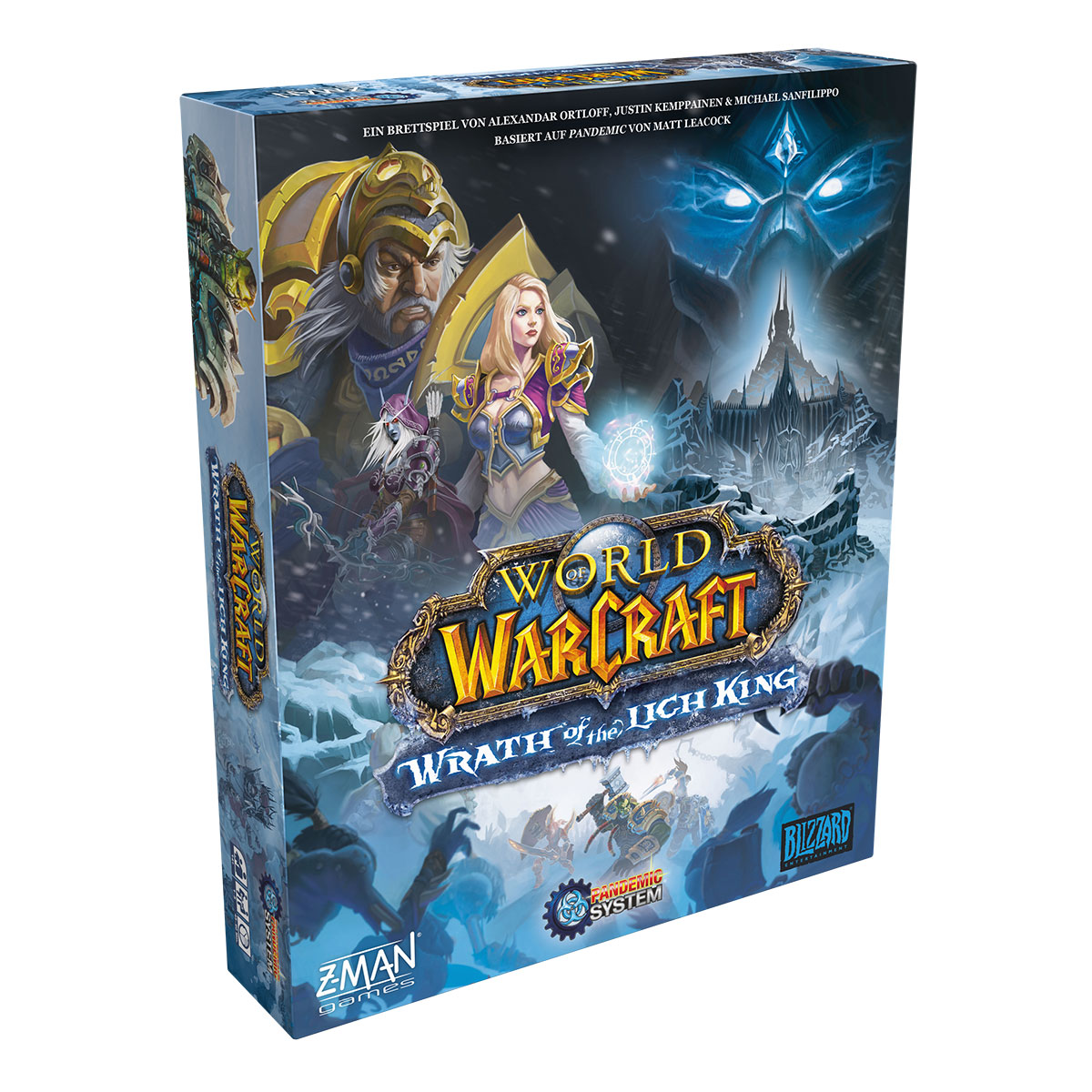

Also, it wasn't just one plague. Over the years, Blizzard has actually leaned into this history. During the Wrath of the Lich King pre-launch event, they launched a "Great Zombie Plague." This time it was intentional. They used the lessons from the Corrupted Blood disaster to design a controlled, week-long event where players could become ghouls. It was controversial, but it showed that the developers realized the "chaos" was actually a unique form of storytelling.

Comparing Corrupted Blood to Modern Events

It’s hard to talk about the World of Warcraft pandemic without looking at the COVID-19 era. During the 2020 lockdowns, various media outlets interviewed Dr. Fefferman again. She pointed out that the "curiosity factor" she saw in WoW—people going to infected areas just to see what was happening—translated directly to people ignoring social distancing to attend parties or gatherings early in the real pandemic.

📖 Related: Why the Clash of Clans Archer Queen is Still the Most Important Hero in the Game

The WoW incident was a precursor to understanding "compliance fatigue." In the game, after a few days of dying, players just got frustrated and stopped playing. In the real world, after months of restrictions, people hit a wall. The stakes are obviously different—your WoW character can resurrect, you can't—but the psychological triggers are remarkably similar.

What This Means for Future Virtual Worlds

As we move toward more complex metaverses and persistent online spaces, the Corrupted Blood incident serves as a cautionary tale. If a world is "living," it can also "get sick." Developers now have to think about "emergent gameplay" that could potentially ruin the experience for everyone.

If you're a developer or just a fan of massive online ecosystems, there are three major takeaways from the World of Warcraft pandemic:

- Systemic Interconnectivity: A small change in one system (pet dismissal) can wreck a completely unrelated system (city commerce).

- The Griefing Variable: Never underestimate the desire of a subset of players to cause chaos for no personal gain.

- The Need for "In-Universe" Communication: Blizzard's biggest struggle was that they weren't talking to players as the authorities in the world; they were talking as developers through forum posts.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Virtual Disasters

If you ever find yourself in the middle of a digital outbreak—whether it's a bug in a new MMO or a scripted event—here is how to handle it based on the 2005 data:

- Avoid Hubs Immediately: The moment you see "piles of skeletons" or unusual debuffs in chat, get out of the main cities. Use your hearthstone to a remote inn.

- Check the Combat Log: Knowledge is power. Seeing exactly how a debuff is jumping (is it proximity? is it a spell?) allows you to adjust your movement.

- Don't Rely on the "Quarantine": In every digital pandemic, players have found ways to bypass developer-imposed barriers. The only safe player is an isolated player.

- Document the Chaos: These events are rare. The Corrupted Blood incident is now a piece of digital history. If you're caught in one, take screenshots and logs. You might be contributing to a future scientific study.

The World of Warcraft pandemic wasn't just a server-side error. It was a mirror held up to society. It showed us that whether we are wearing Tier 2 raid armor or pajamas in our living rooms, our reactions to a threat are deeply, predictably, and sometimes frustratingly human.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

To truly understand the impact of this event, look up the original 2007 Lancet paper by Lofgren and Fefferman. It provides a technical breakdown of the R0 (reproduction number) of Corrupted Blood and offers a sobering look at how a simple "game bug" changed the way we model global health crises. If you're a gamer, check out the "Zombie Infestation" archives from 2008 to see how Blizzard refined the concept into a controlled, yet still chaotic, gameplay mechanic.