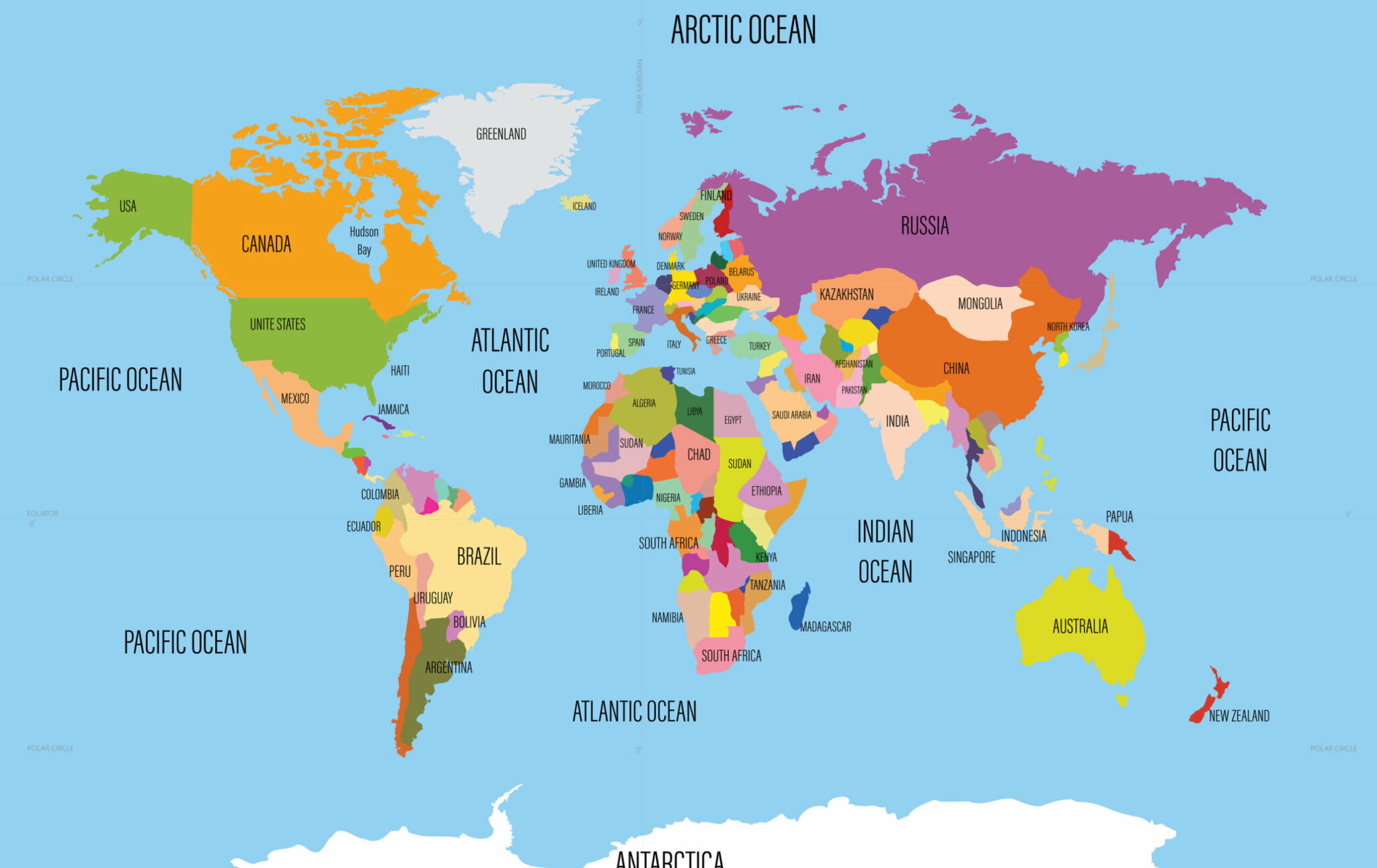

You’ve seen it a thousand times. It’s taped to classroom walls, printed on shower curtains, and pixelated on your phone screen whenever you open Google Maps. But honestly, most people look at a world map of the continents and oceans and see a static, finished puzzle. We assume those blue and green shapes have always been there and always will be. That’s a mistake. The map is alive, and frankly, it's lying to you in more ways than one.

Geography isn't just about memorizing names like "Indian Ocean" or "Africa." It’s about understanding the massive, grinding tectonic plates and the rising tides that dictate where we can actually live. Most of us carry around a mental image of the world that is distorted by the Mercator projection—that 16th-century navigation tool that makes Greenland look as big as Africa. In reality, Africa is fourteen times larger. Let that sink in.

Why the World Map of the Continents and Oceans is Moving Right Now

We talk about continents as these permanent pillars of the earth. They aren't. They’re basically giant rafts of granite floating on a sea of hotter, denser rock. If you look at a world map of the continents and oceans today, you're just seeing a single frame in a very long movie.

Take the Great Rift Valley in East Africa. Geologists like those at the Geological Society of London have been tracking the literal splitting of the African continent. Eventually, a new ocean will form there. It won't happen tomorrow, but the map you’re looking at is technically "expiring" every single second. Then there’s the Southern Ocean. For years, people argued about whether it even existed. In 2021, the National Geographic Society finally joined the party and officially recognized it as the world's fifth ocean, surrounding Antarctica. If your old textbook only lists four, it’s officially a relic.

The continents—Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia—aren't just landmasses. They are the result of billions of years of collisions. And the oceans? They aren't just "water between the land." The Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Southern, and Arctic oceans hold 97% of Earth's water. They regulate our climate, and honestly, we’ve explored more of the surface of the Moon than we have the deep trenches of the Pacific.

The Massive Scale of the Pacific vs. Everything Else

If you turn a physical globe to a certain angle in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, you won't see any land at all. It’s terrifyingly huge. The Pacific covers about 63 million square miles. That is more than all the landmasses on Earth put together. You could drop all seven continents into the Pacific basin and still have room for another Africa.

Deep within this blue expanse lies the Mariana Trench. It’s about 36,000 feet deep. If you put Mount Everest at the bottom, there would still be over a mile of water above the peak. We often treat the "ocean" as one thing, but the Pacific is a different beast entirely compared to the Atlantic. The Atlantic is growing—widening by about an inch or two every year—while the Pacific is technically shrinking as its edges get shoved under the surrounding continents in a process called subduction. This is why the "Ring of Fire" exists. Most of the world’s volcanoes and earthquakes happen here because the Pacific is essentially being swallowed by the rest of the map.

✨ Don't miss: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

Africa: The Continent of Misunderstood Proportions

As I mentioned earlier, the Mercator projection did Africa dirty. Because the map was designed for sailors to maintain a constant compass bearing, it stretches objects near the poles. Since Africa sits squarely on the equator, it looks "normal," while Europe and North America look bloated.

In reality, you can fit the United States, China, India, Japan, and most of Europe inside the borders of Africa. It’s the only continent that stretches from the northern temperate zone to the southern temperate zone. It’s also home to the world’s longest river (the Nile) and its largest hot desert (the Sahara). But even the Sahara is changing. Satellite data from NASA shows "greening" in some areas and expansion in others. The lines we draw on a world map of the continents and oceans are often porous and shifting.

The "Hidden" Continent: Zealandia

You might have been taught there are seven continents. That’s the standard. But back in 2017, a group of eleven geologists published a paper in the Geological Society of America’s journal, GSA Today, arguing for an eighth: Zealandia.

Most of it is underwater. About 94% of it, actually. Only New Zealand and New Caledonia poke above the waves. But it meets all the criteria: it’s elevated above the surrounding oceanic crust, it has distinct geology, and it’s well-defined. This discovery reminds us that the world map of the continents and oceans isn't a closed book. We are still defining what "land" even means when it's submerged.

The Arctic and the Shrinking White Spaces

At the very top of your map is the Arctic Ocean. It’s the smallest and shallowest of the five. For most of human history, it was an impenetrable shield of ice. Not anymore.

The "map" of the Arctic is being rewritten by geopolitics as the ice melts. Countries like Russia, Canada, and the U.S. are literally fighting over where the continental shelves end so they can claim the oil and gas underneath. When the ice disappears, the "ocean" part of the map becomes a shipping lane. This changes global trade routes, making the Northern Sea Route a viable alternative to the Suez Canal. It’s a stark reminder that geography is destiny, and when the geography changes, so does the power balance of the world.

🔗 Read more: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

Why We Need to Stop Ignoring the Southern Ocean

For a long time, the water around Antarctica was just seen as the southern extensions of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. But the Southern Ocean is unique because of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).

This current is the strongest on the planet. It circles Antarctica, acting as a sort of cold-water barrier that keeps the continent frozen. It’s the lungs of the world, absorbing massive amounts of carbon. When cartographers finally added it to the world map of the continents and oceans as a distinct entity, they weren't just being trendy. They were acknowledging a biological and physical reality that scientists had known for decades. The Southern Ocean is the only one that touches three others and completely circles a continent.

Eurasia: One Continent or Two?

If you look at a map, Europe and Asia are clearly one continuous landmass. There’s no ocean between them. We call them two continents for historical and cultural reasons, not because of geology. The Ural Mountains are often cited as the dividing line, but they're more of a bump in the road than a true barrier.

Some geographers prefer the term "Eurasia." If we go by the strict definition of a continent as a large landmass separated by water, then Europe doesn't really qualify as its own. But try telling that to someone in Brussels or Beijing. This is where the world map of the continents and oceans stops being about rocks and start being about identity.

The Indian Ocean: The World's Heat Engine

The Indian Ocean is the warmest in the world. This sounds nice for a vacation, but it’s actually a massive engine for the global climate. It drives the monsoons that billions of people in South Asia rely on for food.

Because it’s landlocked to the north by Asia, it doesn't have the same "flushing" mechanism that the Atlantic or Pacific has with Arctic waters. This makes it particularly sensitive to climate change. As the water warms, it expands, which is a huge problem for low-lying island nations like the Maldives. On your map, the Maldives are just tiny dots. In reality, they are the front lines of a changing global geography.

💡 You might also like: Weather at Lake Charles Explained: Why It Is More Than Just Humidity

How to Actually Use a World Map Today

Maps aren't just for finding where you are; they’re for understanding how things connect. If you want to get a better grip on the world map of the continents and oceans, stop looking at the standard wall map.

- Try a Dymaxion Map: Created by Buckminster Fuller, this map doesn't have a "right side up." It shows the earth as one continuous island in one continuous ocean. It’s great for seeing how close the continents actually are to each other.

- Look at Bathymetric Maps: These show the "terrain" of the ocean floor. You’ll see the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a massive underwater mountain range that’s actually longer than the Andes.

- Check the Gall-Peters Projection: While it looks "stretched" vertically, it preserves the actual size of the continents. It’s a humbling way to see just how massive the Global South really is.

The world map of the continents and oceans is a tool, not a portrait. It’s a simplified version of a messy, spinning, vibrating planet. We use these names—Asia, Atlantic, Australia—to make sense of the vastness, but the reality is much more fluid. The oceans are mixing, the plates are shifting, and the map you use today is just a snapshot of a world in motion.

To get a true sense of the planet, you have to look past the borders. You have to see the currents that move heat from the equator to the poles and the tectonic forces that push mountains into the sky. The map isn't just a guide to where things are; it's a guide to how the Earth works.

Go find a globe. Spin it. Find the Point Nemo in the Pacific—the place furthest from any land. Then find the Himalayas, where the Indian plate is still slamming into Asia. When you look at a world map of the continents and oceans after knowing all this, it doesn't look so static anymore. It looks like a living thing.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Explorer:

- Audit your perspective: Download a "South-Up" map to challenge your North-centric bias. It’s disorienting at first, but it’s a great exercise in mental flexibility.

- Track the changes: Use tools like the NASA Sea Level Change portal to see how the "ocean" part of your map is encroaching on the "continent" part in real-time.

- Explore the deep: Use Google Earth’s ocean layer to "dive" into the Mariana Trench or the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Seeing the topography of the ocean floor changes how you view the blue spaces on a map.

- Support Ocean Conservation: Since the oceans connect every continent, what happens in the Indian Ocean affects the Arctic. Organizations like the Ocean Conservancy work across these "borders" to keep the map healthy.