It was cold. Bitterly, bone-chillingly cold in Central Massachusetts on December 3, 1999. The kind of night where the air feels heavy and sharp, and you can smell the woodsmoke from the triple-deckers across the city. But the smoke coming from 266 Franklin Street wasn't woodsmoke. It was something much darker, much thicker, and far more lethal.

If you grew up in Worcester, or if you’ve spent any time in the fire service, the Worcester Cold Storage fire isn't just a historical event. It is a scar. It’s the night six men went into a brick oven and never came out. Honestly, it’s a story about how a series of small, seemingly insignificant factors—abandoned buildings, a couple of candles, and a labyrinthine layout—collided to create one of the worst firefighting tragedies in American history.

People still talk about it. They talk about it because it changed everything. It changed how we fight fires in "vacant" buildings. It changed the technology on the trucks. But mostly, it’s remembered because of the sheer, suffocating weight of what happened inside those windowless brick walls.

The Building was a Fortress

The Worcester Cold Storage and Warehouse Co. building was a beast. Built in 1906, it was a massive six-story structure of brick and mortar. But it wasn't a normal building. Since it was designed for cold storage, the walls were thick. Crazy thick. We’re talking 18 inches of brick, followed by layers of granulated cork, mineral wool, and polystyrene for insulation.

Basically, the place was a giant Thermos.

By 1999, it had been abandoned for a decade. It was a playground for the homeless and a nightmare for the city. Because it was a "cooler," it had almost no windows. The few that existed had been bricked over or boarded up years prior to prevent theft and squatting. When the fire started—sparked by a knocked-over candle during an argument between two homeless individuals, Thomas Levesque and Julie Ann Loftus—the building did exactly what it was designed to do. It kept the heat in.

The fire smoldered for over an hour and a half before anyone even noticed. Think about that. 90 minutes of heat building up inside a windowless brick box filled with highly flammable cork insulation. By the time the Worcester Fire Department arrived at 6:13 PM, the building wasn't just on fire. It was a pressure cooker waiting to pop.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

The Search for the "Missing"

Firefighters are trained to save lives. That's the mission. When the first crews arrived, they were told that there might be homeless people trapped inside. This is the part that hurts: there was nobody in there. Levesque and Loftus had already fled the building, but they didn't tell anyone the fire had started, and they didn't tell the arriving crews that the building was empty.

So, the men went in.

Firefighters Paul Brotherton and Jerry Lucey were the first to get lost. The layout was a maze. Imagine being in total darkness, surrounded by thick, black, oily smoke that your flashlight can't even penetrate. Now imagine you're in a massive open space with no windows to use as a reference point. You can't see your hand in front of your face. You're trailing a hose line, but the building is so large that you lose your orientation.

They called for help.

That's when the "Worcester 6" tragedy really began to unfold. Lieutenant Timothy Stackpole, James Lyons, Joseph McGuirk, and Jay Lyons went in to find their brothers. They weren't just colleagues; these guys grew up together. They played ball together. They knew each other's kids. In the fire service, you don't leave anyone behind. But the Worcester Cold Storage fire didn't care about bravery. It was a tactical nightmare.

The insulation was the real killer. As the cork and polystyrene burned, it released a thick, black smoke that was actually a fuel source itself. This led to a phenomenon known as "backdraft" and extreme heat conditions that eventually caused the upper floors to become a death trap. The rescuers became the victims.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

Why the Fire Service Will Never Be the Same

You can't look at modern firefighting without looking at what went wrong in Worcester. Before this, the risks of "vacant" buildings were often underestimated. Now, the phrase "risk a lot to save a lot, risk little to save little" is the golden rule. If a building is vacant and there’s no life safety issue, you don't send people into a meat grinder.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) did a massive investigation into the tragedy. Their report, Death in the Line of Duty Report 99-F47, is still required reading for fire recruits today. It points to a few massive failures:

- Lack of thermal imaging: Back then, thermal imaging cameras (TICs) were rare and bulky. Most crews didn't have them. Today, they are standard.

- The "Breadcrumb" problem: In a building that large, you need a way to find your way back. Search ropes are now a staple for large-structure fires.

- Accountability systems: The way we track who is in a building and where they are changed drastically.

- Radio communication: The concrete and brick walls acted like a Faraday cage, killing radio signals.

The city of Worcester didn't just move on. You can't. They built a brand-new fire station, the Franklin Street Station, right on the site where the warehouse once stood. It’s a beautiful building, but it’s also a tombstone. There’s a memorial there. Six bronze helmets. If you ever walk by, it’s quiet. You can feel the weight of the place.

The Human Cost

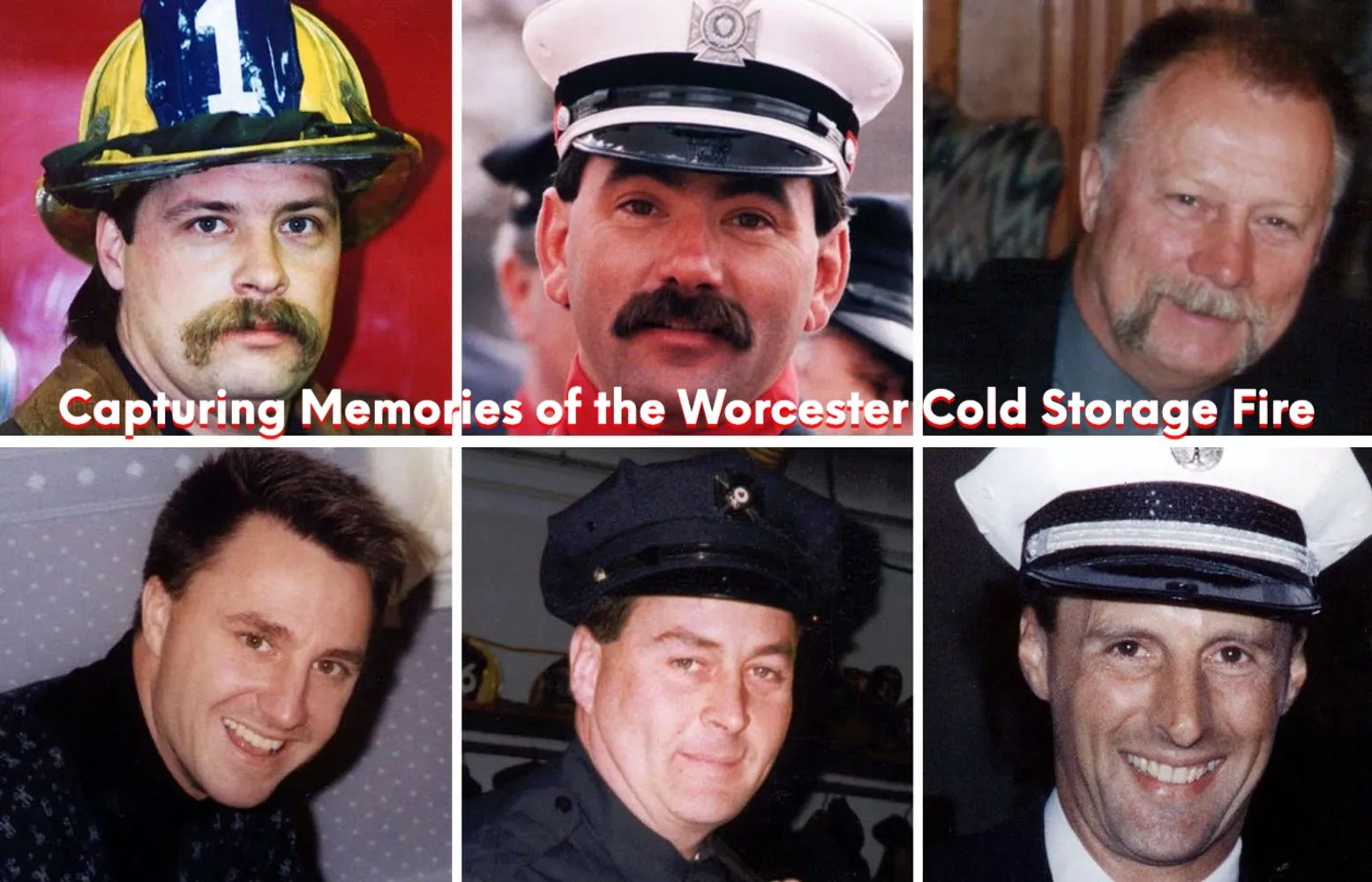

We often talk about fires in terms of "units" and "tactics," but we shouldn't forget who these men were.

- Lt. Thomas Spencer: A veteran who knew the risks but went in anyway.

- Paul Brotherton: A guy who loved his job.

- Timothy Stackpole: He had actually been severely burned in another fire years prior and fought his way back to the job. He was a hero before he even stepped foot in the warehouse that night.

- Jeremiah Lucey: A cousin of the fire chief at the time.

- James Lyons & Joseph McGuirk: Men who were doing exactly what they were trained to do.

The funeral was one of the largest Worcester has ever seen. Thousands of firefighters from all over the world lined the streets. It was a sea of blue uniforms under a gray December sky. It was the moment the world realized that "cold storage" wasn't just a business term; it was a structural hazard that needed a completely different tactical approach.

What Most People Get Wrong

There’s a common misconception that the building collapsed and crushed the men. It didn't. Not initially. The Worcester Cold Storage fire killed through disorientation and air depletion. When you're in a maze and your air tank starts whistling—meaning you have about five to ten minutes of air left—panic is your biggest enemy. These men were elite, but the environment was impossible. They ran out of air while trying to find a way out of a windowless box.

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

The building was eventually demolished, but it took weeks. They had to be incredibly careful because the structure was so unstable. Finding the bodies took days of painstaking work, often in freezing temperatures, with firefighters hand-digging through the charred remains of the cork and brick.

Lessons for the Future

Honestly, if there is any "silver lining"—though that feels like the wrong phrase—it's that the lessons learned in Worcester have saved hundreds of lives since 1999. Every time a commander decides to fight a fire defensively because a building is an unoccupied "taxpayer" or warehouse, they are channel-marking the ghosts of the Worcester 6.

We've seen better GPS tracking for firefighters. We've seen the implementation of "Rapid Intervention Teams" (RIT) that are more highly trained and better equipped than they were twenty-five years ago. The technology for piercing nozzles, which can fight fires through walls without firefighters entering the building, has also seen significant advancement.

Actionable Safety Insights for Property Owners and City Officials

If you are involved in urban planning or commercial real estate, the legacy of the Worcester fire offers very real directives:

- Seal Vacant Buildings Properly: Don't just board them up; secure them in a way that prevents human entry while allowing for emergency egress if necessary.

- Update Fire Maps: Municipalities must keep active, digitized records of "high-hazard" buildings—specifically those with windowless configurations or unusual insulation.

- Pre-Incident Planning: Fire departments should have walk-throughs of large industrial sites before a fire happens. Knowing the floor plan is the difference between life and death.

- Sprinkler Retrofitting: While expensive, retrofitting older industrial buildings with modern suppression systems is the only way to truly mitigate the risk of a "smoldering" start in a brick-and-mortar fortress.

The Worcester Cold Storage fire remains a sobering reminder that bravery isn't always enough to overcome a building designed to keep the world out. We remember the six not just for how they died, but for how their sacrifice forced the world of fire safety to finally catch up to the hazards of the industrial past.

To truly honor them, we have to keep talking about the "why" behind the tragedy. We have to keep demanding better equipment, better training, and smarter fire-ground decisions. Because no one should ever have to go into a windowless box and not come home.

Next Steps for Fire Safety Professionals and History Buffs:

- Review the NIOSH Report: Access the full technical breakdown of the Worcester Cold Storage fire via the CDC/NIOSH database to understand the specific mechanical failures of the day.

- Visit the Memorial: If you are in New England, visit the Franklin Street Fire Station in Worcester to pay respects and see the architectural tribute to the fallen.

- Evaluate Local Hazards: Use GIS mapping to identify windowless cold-storage facilities in your own jurisdiction and ensure RIT protocols are updated for these specific structural types.