Most people think they know the story of Oz. You've got the ruby slippers, the singing munchkins, and that specific shade of sepia-toned Kansas. But honestly? If you only know the 1939 film, you’re missing out on about 95% of the actual Wizard of Oz book series.

L. Frank Baum didn't just write one book and call it a day. He created a sprawling, weird, and sometimes genuinely violent fantasy epic that spans fourteen original novels. And that’s just the beginning. After Baum died, the series kept going under different authors for decades. It's the original cinematic universe, long before Marvel was even a glimmer in anyone's eye.

The Wizard of Oz Book Series is Way Weirder Than You Think

Let’s get the biggest shocker out of the way: the slippers aren’t ruby. In the first book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), they are silver. Hollywood changed them to red because they wanted to show off that fancy new Technicolor technology. It's a small detail, sure, but it sets the tone for how much the "official" version of the story we carry in our heads diverges from the source material.

The books are darker. Much darker.

Take the Tin Woodman. In the movie, he’s a guy in a suit who needs some oil. In the Wizard of Oz book series, his backstory is a straight-up body-horror tragedy. He was a human woodsman named Nick Chopper who fell in love. A wicked witch enchanted his axe, causing it to chop off his limbs one by one. Each time he lost a part of himself, a tinsmith replaced it with metal. Eventually, he was all tin, but he realized the tinsmith forgot to give him a heart, so he couldn't feel love for his fiancée anymore.

That's the kind of stuff Baum was putting in "children's books" at the turn of the century.

Why Dorothy Keeps Going Back

You know that famous line, "There's no place like home"? In the books, Dorothy doesn't seem to believe it as much as Judy Garland did. In fact, by the sixth book, The Emerald City of Oz, Dorothy basically realizes that Kansas is a gray, dusty nightmare where her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry are about to lose the farm to foreclosure.

So, what does she do? She moves them all to Oz permanently.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

She becomes a Princess of Oz. She lives in a palace. She stops aging. It’s a total rejection of the "middle-American grit" theme that the movie celebrates. Baum’s Oz was an escape from the harsh reality of the industrial revolution and the failing American dream of the late 1800s.

The Fourteen "Royal" Books by L. Frank Baum

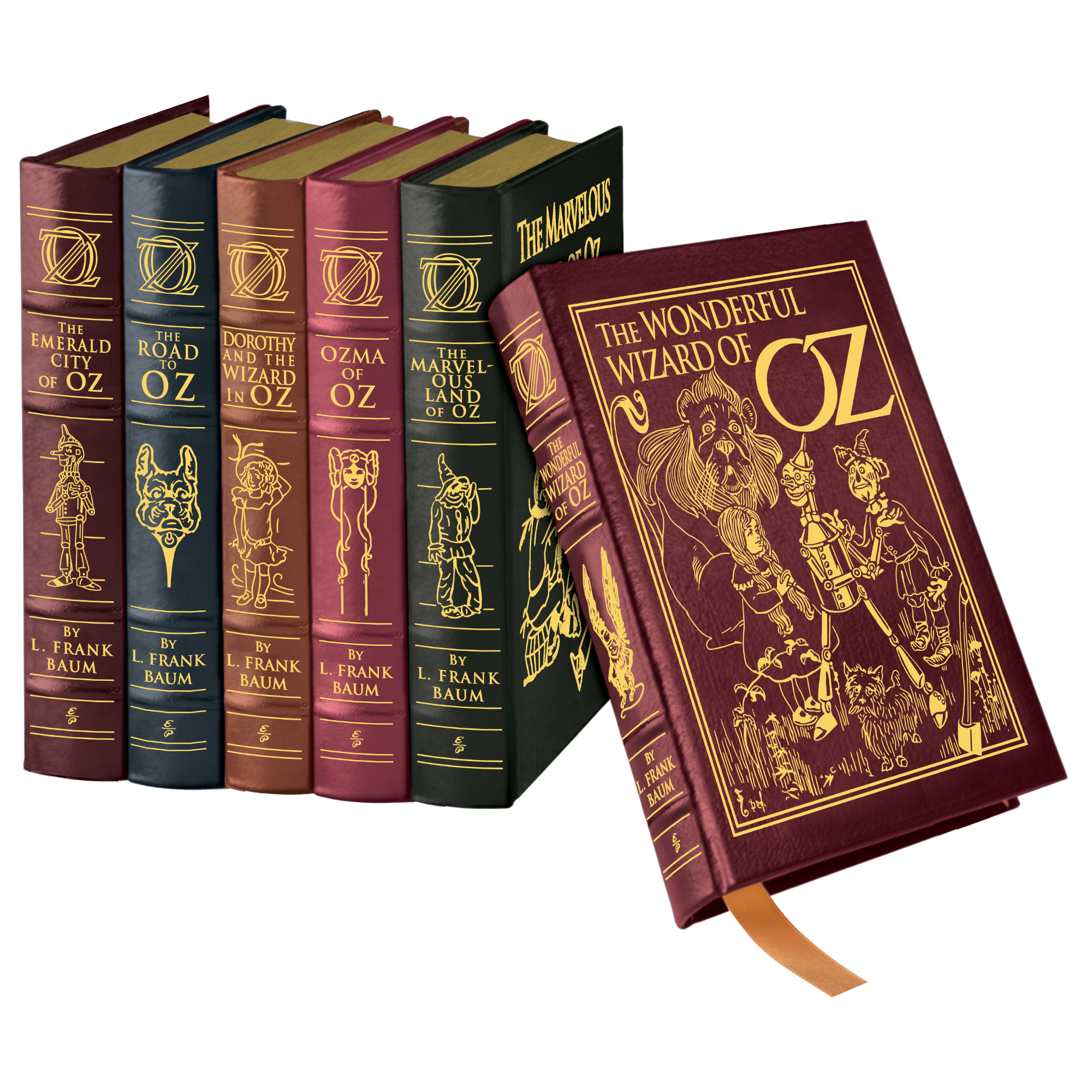

If you’re looking to dive into the Wizard of Oz book series, you have to start with the original fourteen. These are often called the "Famous Forty" (though that includes later authors), but the Baum books are the DNA of the whole thing.

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900): The one everyone knows, sort of.

- The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904): Dorothy isn't even in this one. It follows a boy named Tip who turns out to be—spoiler alert for a 120-year-old book—the enchanted Princess Ozma, the rightful ruler of Oz.

- Ozma of Oz (1907): This is where we meet Billina the yellow hen and TikTok, the clockwork man. It's arguably the best book in the series.

- Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908): An earthquake swallows a carriage, and Dorothy ends up in underground kingdoms.

- The Road to Oz (1909): A bit of a "guest star" book where characters from other Baum stories show up for a birthday party.

- The Emerald City of Oz (1910): Baum tried to end the series here by saying Oz was cut off from the world forever. Fans freaked out.

- The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913): He came back because he needed the money, frankly.

The list continues through Rinkitink in Oz, The Lost Princess of Oz, and finally Glinda of Oz, which was published posthumously in 1920.

The Evolution of the World

The world-building is incredibly dense. Oz is divided into four main quadrants: Munchkin Country (East), Winkie Country (West), Gillikin Country (North), and Quadling Country (South). Each has its own color scheme—blue, yellow, purple, and red.

It’s a rigid system, but Baum constantly broke his own rules.

He introduced the Nome King, a grumpy underground monarch who became the series' recurring villain. He introduced the Shaggy Man, Polychrome (the Rainbow’s daughter), and the Hungry Tiger, who is "hungry" because he has a conscience and refuses to eat babies, even though he really wants to. It's weirdly psychological.

Life After Baum: The Ruth Plumly Thompson Era

When Baum died, the publishers didn't want to stop the gravy train. They hired Ruth Plumly Thompson to keep the Wizard of Oz book series alive. She wrote 21 books—more than Baum himself.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Her style was different. It was lighter, full of puns, and focused more on royalty and knights. Some fans love her for expanding the lore; others feel she made Oz a bit too "cutesy." But you can't talk about the series without acknowledging her. She introduced characters like Jack Pumpkinhead (well, he was Baum's, but she used him more) and the Knight of the Courteous Heart.

Later, other "Royal Historians" took over, including John R. Neill, the man who illustrated almost all the original books. His books are surreal and visually driven, which makes sense given his background.

The Political Allegory Debate (That Might Be Nonsense)

You might have heard in a college history class that the Wizard of Oz book series is actually a secret manifesto about the Gold Standard and the Populist movement of the 1890s.

The theory goes: Dorothy represents the American people, the Scarecrow is the farmers, the Tin Man is the industrial workers, and the Yellow Brick Road is the Gold Standard. The "Silver Slippers" represented the bimetallism movement (silver coinage).

Does it hold up?

Honestly, historians are split. While Baum was a journalist and definitely aware of politics, he always claimed he just wanted to write "modernized fairy tales" to please children. Most modern Oz scholars, like those at the International Wizard of Oz Club, think the "political allegory" thing is a bit of a reach that gained steam in the 1960s. It's fun to think about, but the books stand better as pure, imaginative fantasy.

Why Oz Still Matters in 2026

We live in an era of "reboots" and "reimaginings." From the Wicked musical (and movies) to dark TV adaptations like Emerald City, the Wizard of Oz book series is the well that everyone keeps dipping into.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Why?

Because Baum accidentally created a myth. He created a place that feels real enough to visit but strange enough to be infinite. Oz isn't just a location; it's a vibe. It’s the idea that you can be incompetent, cowardly, or heartless, and yet, through the act of just showing up, you find out you had those qualities all along.

Also, the books are just funnier than the movies. The Scarecrow is a bit of a snob because he has "superior" brains. The Wizard is a total fraud but a likable one. There's a human messiness to the characters that the 1939 film polished away to make them "wholesome."

Common Misconceptions to Clear Up

- The Witch's Name: She doesn't have one in the first book. She's just the Wicked Witch of the West. Gregory Maguire gave her the name "Elphaba" in the 1990s for his novel Wicked.

- The Flying Monkeys: They aren't inherently evil. They are slaves to a magical Golden Cap. Whoever owns the cap can command them three times. In the book, they're actually quite helpful once Dorothy gets the cap.

- The Wizard's Ending: In the book, he doesn't just fly away and leave Dorothy behind by accident. He genuinely tries to take her, but the balloon gets loose. He's more of a tragic figure of circumstance than a bumbling fool.

How to Actually Read the Series Today

If you want to get into the Wizard of Oz book series, don't just buy a "Best Of" collection. You need to experience the illustrations.

W.W. Denslow illustrated the first book with these bold, Art Nouveau lines that defined the look of the characters. After a falling out with Baum, John R. Neill took over for the rest of the series. Neill’s work is incredibly detailed and beautiful. Reading an Oz book without the art is like watching a movie with the screen off.

Most of these books are now in the public domain. You can find them for free on Project Gutenberg or LibriVox. However, if you're a collector, look for the "Books of Wonder" reprints. They preserve the original color plates and the specific way the text wraps around the drawings.

Actionable Next Steps for Oz Newcomers

- Read "The Marvelous Land of Oz" first. Skip the first book if you've seen the movie a thousand times. Book two will blow your mind because it's so different and introduces the "real" Oz politics.

- Check out the International Wizard of Oz Club. They've been around since 1957 and publish a journal called The Baum Bugle. It’s the best place for deep-dive research.

- Track down the John R. Neill illustrations. Google his name and "Oz." The level of detail in his pen-and-ink work is lightyears ahead of what was standard for children's literature at the time.

- Watch "Return to Oz" (1985). While it’s a movie, this Disney cult classic is actually way more faithful to the tone of the Wizard of Oz book series than the 1939 version. It combines elements of The Marvelous Land of Oz and Ozma of Oz. It’s scary, weird, and perfect.

The world L. Frank Baum built is massive. It’s a place where lunch grows on trees (the lunch-box trees in Ozma of Oz are a personal favorite) and where death is almost impossible. It’s a strange, American utopia that hasn't lost its shine in over a century. If you’ve only ever followed the yellow brick road on a TV screen, you’re only halfway home.

The real Oz is waiting in the pages, and it’s a lot more interesting than Kansas ever was.