Lake Superior is a graveyard, sure. But usually, the ships that go down are old wooden schooners or vessels caught in "November Witch" gales that would sink a mountain. The Western Reserve steamer shipwreck is different. It’s haunting because it shouldn't have happened. The ship was a marvel. It was the pride of the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company, a massive steel-hulled giant launched in 1890 that was supposed to represent the future of Great Lakes shipping.

Then, on a relatively calm August night in 1892, it just... broke.

If you’re standing on the shore of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula today, looking out toward Deer Park, you’re looking at the site of one of the most baffling and tragic maritime disasters in American history. It wasn't a collision. It wasn't a fire. The ship literally fractured in two while carrying the owner and his entire family on a summer pleasure cruise.

The Night the Steel Failed

August 30, 1892. The Western Reserve was "running light," meaning it had no cargo. It was heading upbound toward Two Harbors, Minnesota, to pick up iron ore. On board was Peter Minch, the main man behind the Kinsman Transit Company and a heavy hitter in the Cleveland maritime scene. He brought his wife, his son, his daughter, and even his sister-in-law along for the trip. It was supposed to be a vacation.

The water wasn't even that rough. I mean, it was choppy, yeah, but nothing a 300-foot steel vessel couldn't handle. Suddenly, around 9:00 PM, a massive crack echoed across the deck. It sounded like a cannon shot.

The ship had buckled.

You have to imagine the sheer terror of that moment. One minute you're sitting in the captain’s cabin, and the next, the very floor beneath you is splitting. Within ten minutes, the Western Reserve was gone. The steel hull, which everyone thought was invincible compared to the old wooden boats, had failed catastrophically.

👉 See also: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

The Lone Survivor’s Nightmare

There were two lifeboats launched. One capsized almost immediately in the wake of the sinking ship. The other, carrying the Minch family and several crew members, struggled through the surf for hours. They were so close to the shore. They could see the lights.

But Lake Superior is a cold, heartless place.

As the lifeboat reached the sandbar near Deer Park, a massive wave flipped it. Everyone went into the water. Out of 31 people on board the Western Reserve, only one man made it to the beach alive: Harry Stewart, the wheelsman. He watched the Minch family drown in the surf right in front of him.

Stewart had to trek through miles of dense, mosquito-infested woods to reach the Life-Saving Station at Muskallonge Lake. When he finally staggered in, he was barely coherent. His account is the only reason we know the specific details of the Western Reserve steamer shipwreck today. Without him, the ship would have just been another "missing" vessel on the Great Lakes.

Why Did It Snap? (The Bessemer Problem)

For years, people argued about why the ship broke. Was it a rogue wave? Was the ballast off? Honestly, the truth is much more boring and much more terrifying: bad metallurgy.

In the 1890s, steel was the "new" thing. The Western Reserve was built using Bessemer steel. At the time, engineers didn't fully understand "brittle fracture." Basically, the steel used in the hull was too high in phosphorus and sulfur. When the temperature of the water dropped or the ship hit a certain frequency of vibration while empty, the steel became as brittle as glass.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

- The ship didn't bend.

- It didn't dent.

- It shattered.

The Western Reserve was a guinea pig for a technology that wasn't ready. Following the disaster, Lloyd’s of London and other maritime insurers started looking much closer at the chemical composition of Great Lakes steel. They realized that the "strength" of steel was a lie if the material couldn't handle the localized stresses of a Great Lakes chop.

Comparing the Sisters: The W.H. Gilcher

Just two months after the Western Reserve went down, its sister ship, the W.H. Gilcher, also vanished. It was built with the same steel, in the same way. It disappeared in Lake Michigan with all hands. That was the nail in the coffin for that specific type of early Bessemer steel construction. It changed how we build ships forever.

Finding the Wreckage Today

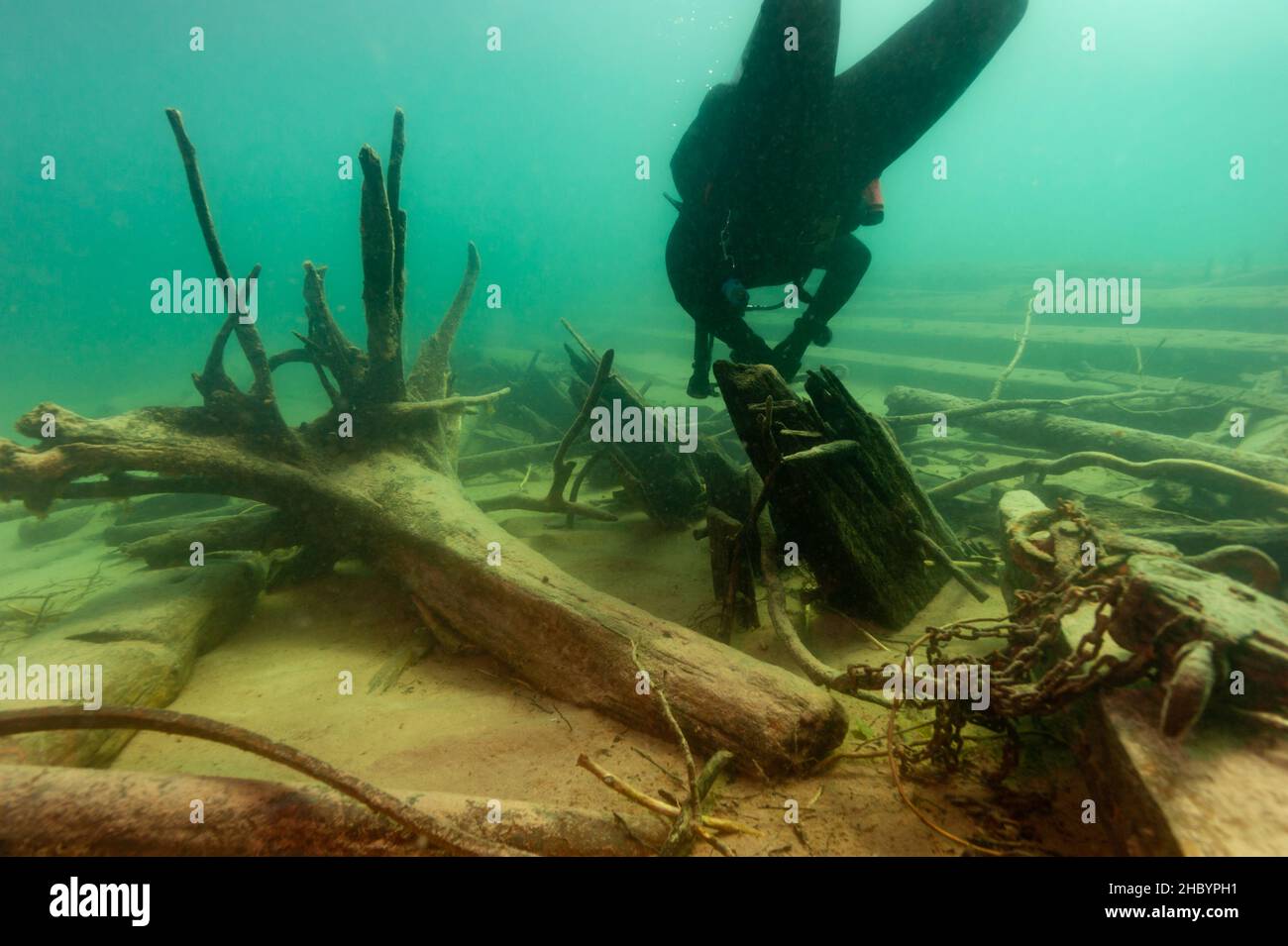

For over a century, the Western Reserve sat in the dark. It’s deep. We’re talking 600 feet of water. In 1988, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society finally located it using sonar.

What they found was a ghost.

The ship is in pieces. The bow and stern are separated by a significant distance, confirming Stewart’s story that the boat broke clean in half. Because the water is so cold and lacks much oxygen at that depth, the wreckage is eerily preserved. You can still see the mast and the engine room equipment.

It's a protected site. You can't just go diving there—not that most people could, given the extreme depth. It requires specialized mixed-gas diving or ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles). If you want to see artifacts, your best bet is the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point. They have items recovered from the area and a massive amount of documentation on the Minch family.

🔗 Read more: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

Lessons from the Deep

The Western Reserve steamer shipwreck isn't just a story about a tragedy; it’s a case study in engineering hubris. We thought we had conquered the lakes with steel. We hadn't.

If you’re planning to visit the area or research Great Lakes shipwrecks, here is how you can actually engage with this history:

Visit the Whitefish Point Museum

Don't just look at the lighthouse. Go into the wreck gallery. They have a specific focus on the steel-hull failures of the 1890s. It puts the Western Reserve into a context that makes you realize how lucky we are that modern metallurgy is a regulated science.

Hike the Deer Park Shoreline

Drive out to Muskallonge Lake State Park. Walk the beach toward the east. This is where Harry Stewart crawled out of the water. When you see how rough the surf is even on a "nice" day, you'll understand why the rest of the crew didn't stand a chance once that lifeboat flipped.

Research the Genealogies

The Minch family was massive in Cleveland. If you're into local history, looking into the Kinsman Transit Company archives gives you a look at the business side of this disaster. The financial hit was huge, but the loss of the family's lineage was what really shocked the socialites of the era.

Check the Weather Reports

If you're a boater, use the Western Reserve as a reminder. The ship was "too big to fail" until it wasn't. Lake Superior creates its own weather patterns. Always check the NOAA Nearshore Marine Forecast specifically for the Whitefish Point to Munising sector.

The lake doesn't care how much your boat cost or what it's made of. The Western Reserve proved that over 130 years ago, and it remains one of the most sobering reminders of the power of Superior. It’s a grave, a classroom, and a mystery all wrapped into one scattered pile of 19th-century steel.

Go to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society website and look at the sonar images of the break point. You can see the jagged edges of the steel where it failed. It’s a chilling visual that explains more than any textbook ever could about why this ship—and the people on it—never stood a chance.