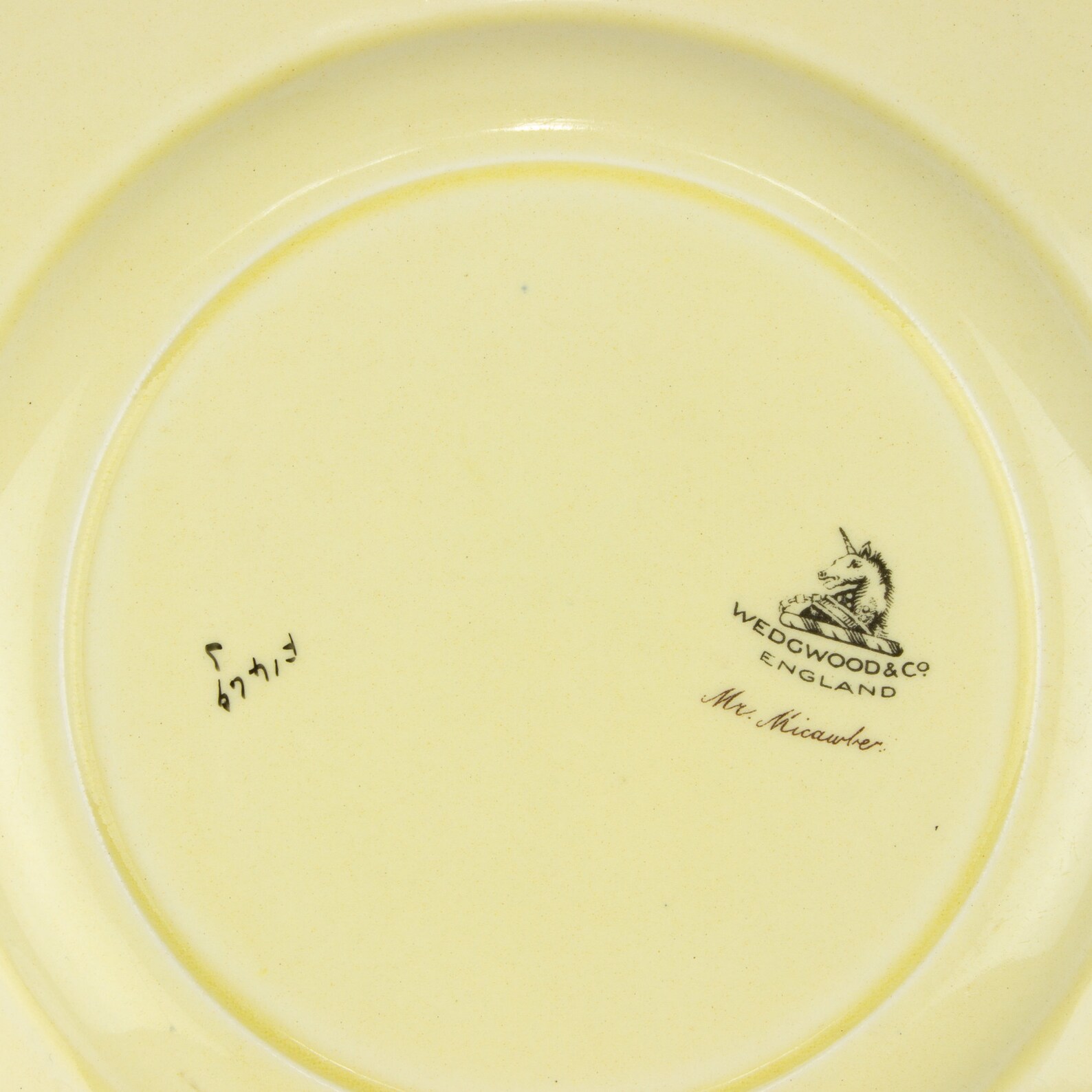

You’re at a thrift store or maybe digging through your grandmother’s attic when you spot it. A creamy white plate with a crisp blue pattern. You flip it over, see the name "Wedgwood," and your heart skips. You’ve struck gold, right? But then you notice something odd. There’s a unicorn. A little prancing mythical beast staring back at you.

Honestly, this is where most people get tripped up.

If you see a unicorn on your ceramics, you aren't looking at the world-famous "Jasperware" Wedgwood founded by Josiah Wedgwood in 1759. You’ve actually found a piece from Wedgwood & Co, a completely separate company based in Tunstall. They were cousins, sure, but in the world of high-stakes antique collecting, that "& Co" makes a massive difference in history, style, and—let's be real—your bank account.

The Identity Crisis: Wedgwood vs. Wedgwood & Co

It’s a classic case of family branding gone wild. Enoch Wedgwood, a distant cousin of the famous Josiah, founded Wedgwood & Co in 1860. He took over a firm called Podmore, Walker & Co and decided to use his own name. Smart business? Maybe. Confusing for us 160 years later? Absolutely.

The Wedgwood & Co unicorn mark was the company's way of standing out while leaning into the prestige of the name. While the "real" Wedgwood used impressed names or an urn logo, Enoch’s outfit went for the unicorn.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

It’s a bit of a "Diet Coke vs. Coke" situation. Both are soda, but they aren't the same thing. The Tunstall-based Wedgwood & Co specialized in what they called "Ironstone" or "Royal Semi-Porcelain." This was the sturdy, everyday stuff meant for the growing middle class, particularly in the American market.

Decoding the Unicorn: What the Marks Actually Mean

You can actually date these pieces pretty accurately just by looking at how the unicorn is "dressed." The mark evolved as the company grew and changed hands.

The Early Days (1860–1890)

In the beginning, the mark was often just the unicorn's head or a full unicorn with the words Wedgwood & Co. If your piece says this but doesn't have the word "England," it’s likely pre-1891. Why? Because the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 forced all imports into the U.S. to show their country of origin. No "England"? It’s a Victorian original.

The "Ltd" Era (1900–1965)

In 1900, the firm became a limited company. This is a huge "tell." If the mark says Wedgwood & Co Ltd (or sometimes just Ld), you know for a fact it was made after the turn of the century. Some of these marks even have a weird "floating" Ltd that looks like it was squeezed in as an afterthought because they didn't want to pay for a whole new stamp. Potters were frugal like that.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

The Imperial Years

Sometimes the unicorn is paired with a crown or the words Royal Semi-Porcelain. Don't let the "Royal" fool you—it wasn't necessarily made for the Queen. It was a marketing term used to describe a specific type of durable earthenware that looked like porcelain but didn't cost a month's wages.

Why This Mark Actually Matters Today

Is it a fake? No. Wedgwood & Co was a legitimate, high-quality Staffordshire pottery. They produced some of the most iconic "Asiatic Pheasants" and "Blue Willow" patterns you’ll ever see.

In fact, some collectors prefer the Wedgwood & Co unicorn mark because the pieces feel more "human." They were the plates families actually ate off of. They have character. They aren't museum pieces kept behind glass; they are survivors of a century of Sunday dinners.

However, if you're looking for that signature matte-blue Jasperware with white classical figures, the unicorn is a red flag. Josiah’s company (the one that still exists today) actually ended up buying the remains of Enoch’s company in 1980. They renamed the factory "Unicorn Pottery," which is a poetic, if slightly ironic, end to the family rivalry.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Quick Identification Checklist

If you’re staring at a mark right now, run through this:

- Is there a unicorn? It's Enoch Wedgwood (Tunstall), not Josiah (Barlaston/Etruria).

- Does it say "Ltd"? It’s post-1900.

- Is there a month/year code? Look for impressed numbers like "1034." That would mean October 1934. They were surprisingly organized with their dating.

- Is it "Royal Stone China"? This was their trademark for heavy-duty, nearly indestructible kitchenware.

The Actionable Truth

Don't toss it just because it isn't "Josiah" Wedgwood. These pieces are still highly collectible, especially the transferware in deep blues and mulberry tones.

Here is what you should do next:

- Check for "crazing": Run a fingernail over the surface. If you feel tiny cracks in the glaze, it’s older, but it also means you shouldn't put it in the dishwasher. Hand wash only.

- Verify the pattern name: Often, the pattern name (like "Chusan" or "Honolulu") is printed right above or below the unicorn. Searching for the specific pattern name plus "unicorn mark" will give you a much better idea of its current market value.

- Check the "Ltd" spacing: If the "Ltd" looks misaligned compared to the rest of the text, you likely have an early 1900s piece from the transition period, which is a fun bit of history to share.

Knowing the difference between these two "Wedgwoods" doesn't just make you look smart at antique shows—it saves you from overpaying for a name while helping you appreciate a rugged, beautiful piece of Staffordshire history that stands perfectly well on its own four hooves. Or, well, one horn.