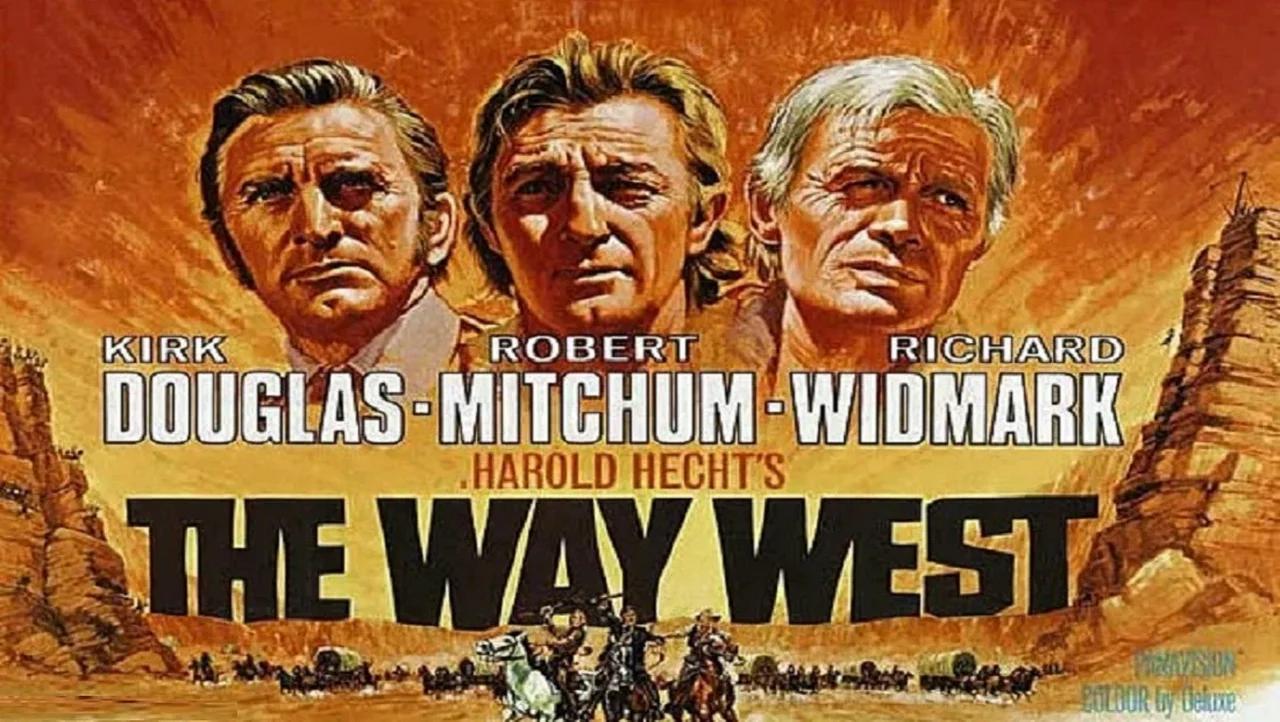

Making a massive Western in the late sixties was a gamble. Honestly, it was a time when the "Old Hollywood" style was crashing head-first into the gritty, cynical vibes of the New Hollywood era. The Way West, released in 1967, sits right in the middle of that wreckage. It’s got the big stars—Kirk Douglas, Robert Mitchum, Richard Widmark—and a Pulitzer Prize-winning source novel. On paper, it should’ve been a masterpiece. Instead, it became a cautionary tale about what happens when you have too many legendary egos on one set and a studio that can't decide if it's making a family adventure or a psychological thriller.

If you’ve seen it, you probably remember the scenery. It's gorgeous. They shot the whole thing on location in Oregon, and it looks it. No soundstages. No fake backdrops. Just raw, dusty trails. But the story? That's where things get kinda messy.

What Actually Happens in The Way West

Basically, the plot follows a wagon train leaving Missouri in 1843, headed for the Oregon Territory. Kirk Douglas plays Senator William Tadlock, a man who isn't just looking for a new home; he wants to build a literal utopia. He’s obsessed. He’s the kind of guy who whips his own son to prove a point about discipline. Douglas plays him with this vibrating intensity that makes you wonder if he’s the hero or the villain. Usually, in these movies, the leader is the "good guy." Tadlock is... not that.

Then you have Robert Mitchum as Dick Summers. He’s the scout. Mitchum was basically playing himself at this point—stoic, tired, and clearly over the drama. He's the one who knows the land, but he’s also losing his eyesight, which adds a layer of "one last job" melancholy to the whole thing. Richard Widmark rounds out the trio as Lije Evans, a farmer who just wants a better life but constantly clashes with Tadlock’s borderline dictatorial leadership.

The movie is famous (or maybe infamous) for a few specific things:

- The Cliff Scene: This is genuinely impressive. They actually lowered wagons over a massive cliff using ropes. No CGI back then, obviously. It’s one of the most stressful sequences in 60s cinema.

- Sally Field’s Debut: Yep, this was her first movie. She plays Mercy McBee, and her subplot involves an unplanned pregnancy and some pretty heavy themes for a 1967 "family" Western.

- The Indian Conflict: There’s a scene where a settler accidentally kills the son of a Sioux chief, mistaking him for a wolf. The fallout is brutal and doesn't exactly paint the settlers in a heroic light.

Why it Flopped and What Went Wrong Behind the Scenes

You've probably heard that Kirk Douglas was a bit of a "handful" on sets. On The Way West, that was an understatement. Reports from the time suggest he was constantly trying to direct the other actors, which didn't sit well with veterans like Mitchum and Widmark. Mitchum, in particular, was famous for his "zero effort" cool, and having Douglas breathe down his neck about motivation probably didn't help the chemistry.

Director Andrew V. McLaglen was a protégé of John Ford, and he tried to capture that Ford-esque epic scale. But United Artists, the studio, got cold feet. They reportedly hacked about 20 minutes out of the beginning of the film before it hit theaters. This left the character introductions feeling rushed. One minute they're in Missouri, the next they're halfway across the continent, and you’re left wondering why these people hate each other so much already.

Critics at the time were pretty savage. Roger Ebert gave it a mediocre review, essentially saying the film gets buried under its own scenery and clichés. It wasn't a "disaster" in the sense that it was unwatchable, but for the budget they spent, it was a massive disappointment.

Historical Accuracy vs. The Novel

The film is based on A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s novel, which is a legitimate piece of literature. The book is way more internal. It’s about the slow, grinding psychological toll of moving thousands of miles. The movie, naturally, had to add more "action."

In the book, Tadlock isn't even a Senator, and he doesn't die some dramatic death falling off a cliff. He actually gets kicked out of the group much earlier because he's a jerk. The movie keeps him around because, well, you don't pay Kirk Douglas top dollar to disappear halfway through the second act.

Also, a quick reality check for history buffs: wagon trains mostly used oxen because they were stronger and cheaper than horses. In the movie, you see a weird mix of horses, mules, and oxen that doesn't really make sense for a 2,000-mile trek, but hey, horses look better on a movie poster.

✨ Don't miss: South Park AI Trump Video: What Really Happened with that Deepfake

Is It Worth Watching Now?

Honestly? Yes. Even with its flaws, The Way West is fascinating. It’s a "transitional" film. It has the grand orchestral score and the wide-screen vistas of the 1950s, but the characters are dark and messed up in a way that feels like the 1970s.

If you’re a fan of Westerns, you should watch it just to see the "Big Three" (Douglas, Mitchum, Widmark) together. It’s the only time they all shared the screen in this capacity. Plus, the cinematography by William H. Clothier is top-tier. It captures the Pacific Northwest in a way few films have managed since.

What you should do next:

If you want to see how this story was supposed to be told, go find a copy of A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s original novel. It provides the depth and character motivation that the studio’s "hack and slash" editing job removed from the film. After that, track down the 122-minute theatrical cut of the movie—just keep an eye out for that cliff scene. It’s still one of the best practical stunts in Hollywood history.