History is messy. If you look at the 1730s, you’ll find a Europe that was basically a tinderbox waiting for a single dead king to set it off. That king was Augustus II, and when he died in 1733, the War of the Polish Succession kicked off. It sounds like a localized dispute about who gets to sit on a throne in Warsaw, right? Wrong. This was a continental brawl that dragged in everyone from the French Bourbons to the Russian Romanovs. It wasn’t just about Poland. It was about who ran the world.

Most people haven't heard of it. That's a shame. It’s a masterclass in backroom deals and dynastic ego.

The Setup: Two Men, One Throne

When Augustus II passed away, Poland-Lithuania had a weird system called an "elective monarchy." Instead of a crown just passing to a son, the local nobles—the Szlachta—got to vote. This sounds democratic until you realize that every major power in Europe was bribing those nobles to pick their guy.

On one side, you had Stanisław Leszczyński. He’d actually been the King of Poland before but got kicked out. He had a massive ace up his sleeve, though: his daughter was Marie Leszczyńska, the wife of King Louis XV of France. Basically, France wanted their father-in-law on the throne to create a pro-French bloc in the East.

On the other side stood Augustus III, the son of the late king. He had the backing of Russia and the Holy Roman Empire (Austria). They didn't necessarily love him, but they hated the idea of a French puppet sitting in Poland.

It was a classic proxy war.

France vs. Everybody

The fighting didn’t actually happen much in Poland. That’s the irony of the War of the Polish Succession. While the Polish nobles were arguing and getting intimidated by Russian troops, the real blood was being spilled in the Rhineland and down in Italy.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

France, led by the elderly but sharp Cardinal Fleury, knew they couldn't easily march an army into the heart of Poland. So, they hit the Habsburgs (Austria) where it hurt. They teamed up with Spain and Savoy-Sardinia to snatch up Austrian territories in Italy. It was a massive land grab disguised as a succession dispute.

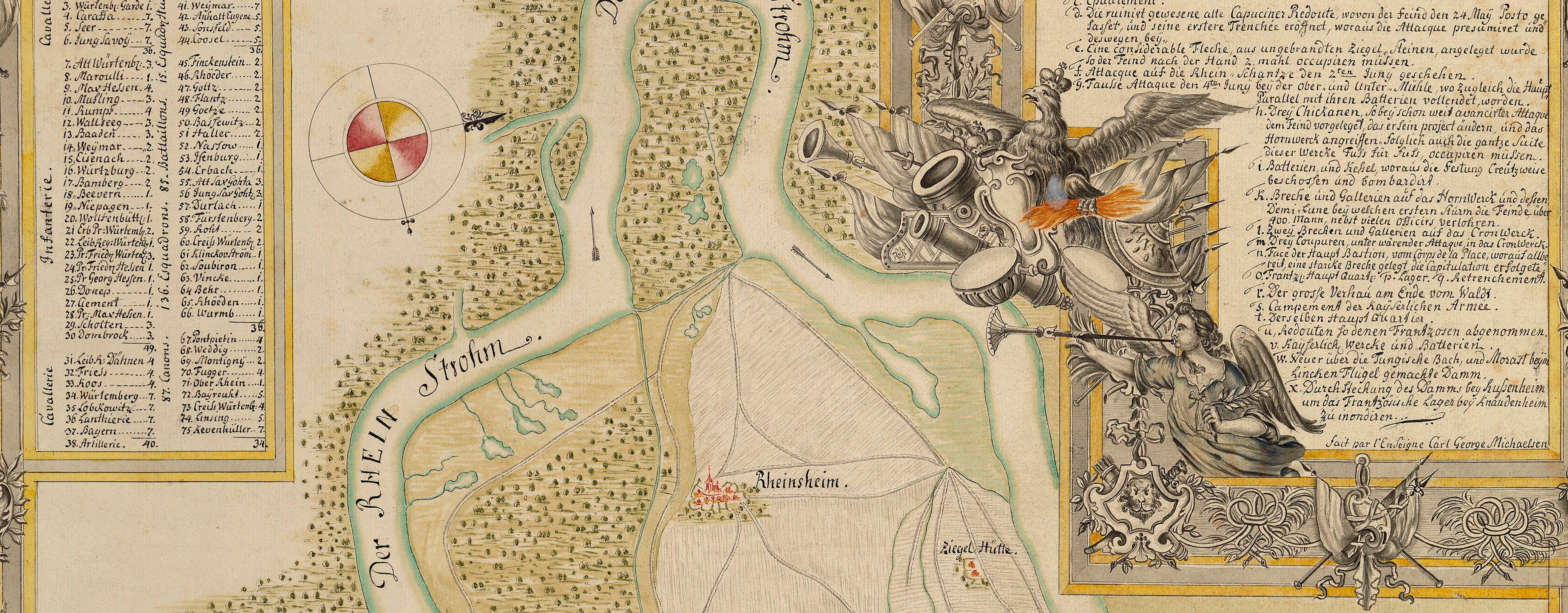

Think about the scale here. You had French generals like the Duke of Berwick (who actually got his head blown off by a cannonball at the Siege of Philippsburg) fighting along the Rhine, while Spanish troops were busy conquering Naples and Sicily.

Why did Russia care?

Russia, under Empress Anna, was just starting to feel its power. They wanted to prove that no king could sit in Warsaw without their permission. They sent 30,000 troops—a huge number for the time—to ensure Augustus III won. This was the moment Russia effectively turned Poland into a protectorate.

Stanisław Leszczyński? He had to flee to Danzig (Gdańsk). He waited for French ships to save him. They sent a small force, but it wasn't enough. The French fleet was intercepted, and eventually, Stanisław had to escape the city disguised as a peasant. It's the kind of stuff you'd see in a movie, honestly.

The Peace That Redrew the Map

By 1735, everyone was tired. The fighting slowed to a crawl. The Treaty of Vienna (eventually finalized in 1738) is where the real "magic" happened. This wasn't a peace treaty that solved Polish problems; it was a real estate swap.

- Augustus III got the Polish throne.

- Stanisław Leszczyński got the Duchy of Lorraine as a consolation prize. When he died, it would go to France. This was a huge win for the French.

- Austria lost Naples and Sicily to a branch of the Spanish Bourbons. To make up for it, they got the tiny Duchies of Parma and Piacenza.

- Francis Stephen, the Duke of Lorraine, was forced to give up his ancestral lands. In exchange, he got the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. This mattered because he was engaged to Maria Theresa, the future Empress of Austria.

Basically, they moved entire populations around like chess pieces to make sure the "Balance of Power" didn't tip too far in any one direction.

🔗 Read more: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

The Long-Term Fallout

We often overlook the War of the Polish Succession because it sits between the bigger "Great" wars—the War of the Spanish Succession and the Seven Years' War. But it changed everything.

It signaled the decline of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The fact that foreign powers could simply impose a king on them showed that Poland was no longer a sovereign player; it was a prize to be carved up. A few decades later, Poland would disappear from the map entirely.

It also solidified the Bourbon-Habsburg rivalry. France got closer to its goal of reaching its "natural borders" by securing Lorraine. Spain regained a foothold in Italy that would last until the 19th century.

Honestly, the human cost was significant but often buried in the footnotes. Thousands died in sieges like Philippsburg or Kehl for a king that most of them would never meet.

What We Get Wrong About This War

People often think 18th-century wars were "gentlemanly." They weren't. The Siege of Danzig was brutal. Civilians starved while the French and Russians traded artillery fire. There’s also a misconception that this was a "failed" war for France. On paper, their guy (Stanisław) lost the throne. But strategically? France won big by gaining Lorraine.

You also can't ignore the role of the "Pragmatic Sanction." This was a legal document Emperor Charles VI was obsessed with, trying to ensure his daughter Maria Theresa could inherit his lands. He gave up territory in this war just to get other countries to sign that piece of paper. Spoiler alert: they ignored it the second he died.

💡 You might also like: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

Modern Lessons from 1733

What can we learn from the War of the Polish Succession today?

First, proxy wars are never just about the country where the fighting starts. Poland was the excuse; Italy and the Rhineland were the targets. Second, diplomacy is often just a way to formalize what happened on the battlefield, but with a lot more fancy clothes and expensive ink.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to understand the modern borders of Europe or why certain royal houses ended up where they did, you have to look at these "minor" wars. They are the connective tissue of history.

- Look at the Map: Open a map of Europe from 1700 and compare it to 1740. Focus on the border between France and Germany (Lorraine) and the southern tip of Italy. That's the visual legacy of this war.

- Research the "Secret Cabinet" Diplomacy: The 1730s were the peak of "Cabinet Wars." Decisions were made by a few ministers in small rooms, not by public sentiment or national identity.

- Trace the Rise of Russia: This war was one of the first times Russian boots were on Western European soil. It set the stage for Russia's role as the "Gendarme of Europe" in the 1800s.

- Visit the Sites: If you're ever in Nancy, France, look at the Place Stanislas. It's a gorgeous square built by the man who lost the Polish throne but won a duchy. It’s a literal monument to the compromise that ended the war.

The conflict wasn't just a footnote. It was the moment the old medieval style of "who is the king" met the modern reality of "who has the biggest army and the most gold." Poland paid the price, and the rest of Europe moved the furniture around.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly grasp the impact of the War of the Polish Succession, your next step should be researching the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It started only two years after the Treaty of Vienna was finalized. You will see immediately how the territorial swaps of 1738 directly caused the massive explosions of the 1740s, specifically regarding Frederick the Great's seizure of Silesia. Understanding these two conflicts as a "double feature" provides the clearest picture of how the Enlightenment-era balance of power actually functioned on the ground.