If you stare at a standard war in pacific map long enough, you start to realize why the logistics of 1941 to 1945 were a total nightmare. Honestly, most maps we see in school textbooks do a terrible job of showing the sheer emptiness of it all. You see a few dots for Hawaii, a blob for Australia, and some tiny specks for the Solomon Islands, and you think, "Okay, they just sailed from point A to point B."

But it wasn't like that. Not even close.

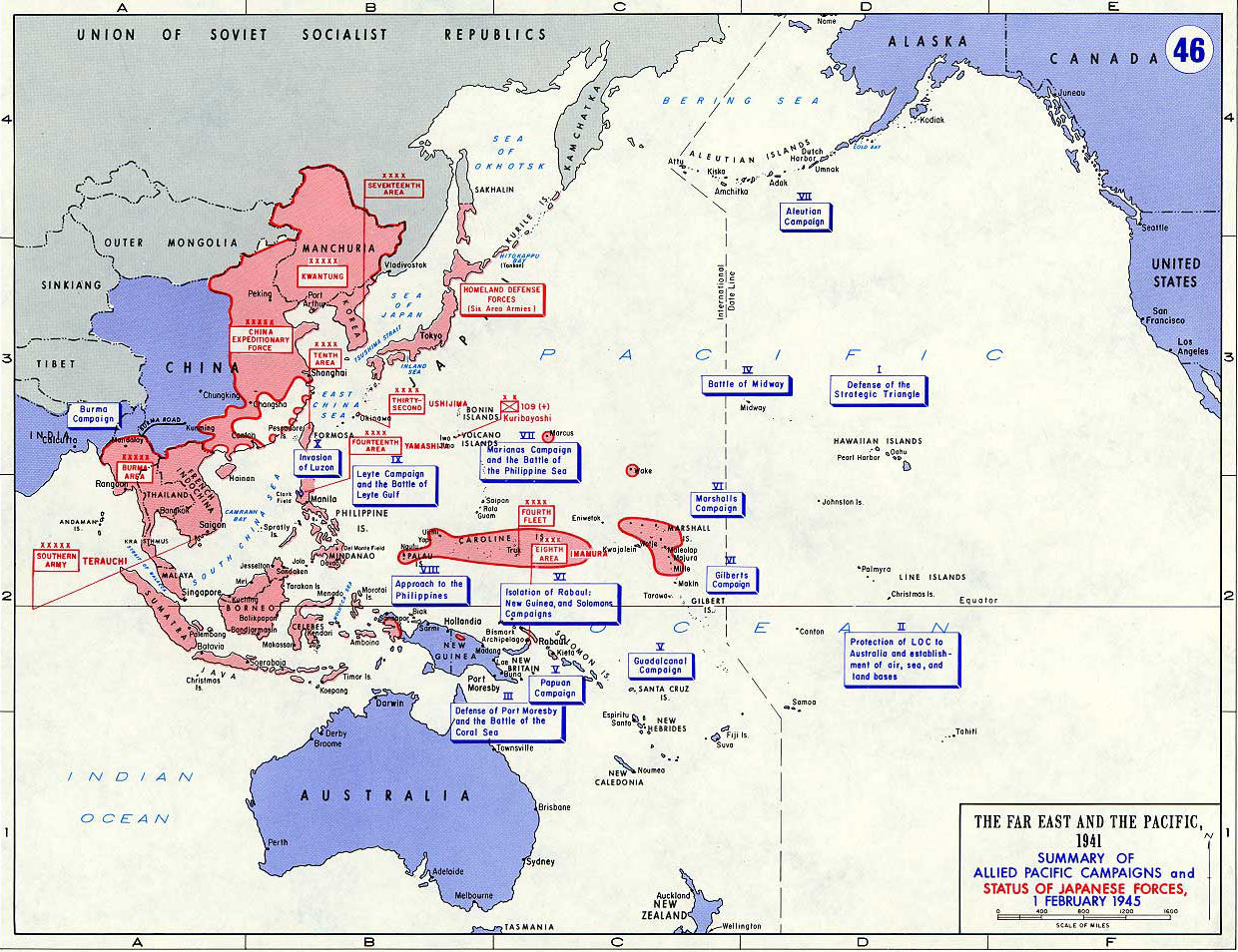

The Pacific Theater covered about one-third of the entire Earth's surface. That is more than all the landmasses on the planet combined. When people look for a war in pacific map, they’re usually trying to understand how a conflict could possibly span 60 million square miles. It’s hard to wrap your brain around the fact that Nimitz and MacArthur were moving armies across distances that make the European front look like a backyard skirmish.

The Tyranny of Distance

The US Navy had a term for this: "the tyranny of distance." Basically, if you were a sailor in 1943, you weren't just fighting the Imperial Japanese Navy; you were fighting the Pacific Ocean itself.

Look at the distance between San Francisco and Brisbane. It's over 7,000 miles. Compare that to the Atlantic, where the hop from New York to London is roughly 3,500 miles. You’ve got double the distance, half the infrastructure, and a thousand tiny islands that aren't even big enough to support a runway. This fundamentally changed how the map functioned. In Europe, the map was about lines on the ground. In the Pacific, the map was about "points" and "reaches."

The Strategy of the Dots

Historians like Samuel Eliot Morison, who basically wrote the definitive history of US Naval operations, pointed out that the war in pacific map was essentially a series of stepping stones. This is what we now call "Island Hopping." But even that term feels a bit too organized. It was more like a violent game of leapfrog.

👉 See also: Otay Ranch Fire Update: What Really Happened with the Border 2 Fire

The goal wasn't to capture every island. That would’ve taken fifty years. Instead, the strategy—championed by Douglas MacArthur and Chester Nimitz—involved bypassing heavily fortified Japanese "strongpoints" like Rabaul. Why fight a bloody battle for a base when you can just seize the island next to it, build an airfield, and let the guys on Rabaul starve?

It was brilliant. And it was terrifying for the soldiers who knew that if their ship sank in the middle of these vast blue gaps, they were hundreds of miles from anything resembling help.

How the Map Changed After 1942

If you look at a war in pacific map from early 1942, it’s depressing. Japan’s "Rising Sun" flag was everywhere. They had the Philippines, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, and were knocking on the door of Australia. The "Southern Resource Area" was theirs. They had the oil, the rubber, and the tin.

But then came Midway.

Midway is a tiny speck. It’s a pair of sand islets. If you look at it on a global map, it's a pixel. Yet, because of its position, it was the "sentry" for Hawaii. When the Japanese lost four carriers there, the map started to shrink for them. The expansion stopped. The lines on the war in pacific map began to recede, not in a straight line, but in a jagged, two-pronged approach.

✨ Don't miss: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

- The South Pacific Drive: MacArthur pushing up through New Guinea toward the Philippines. This was muddy, jungle warfare.

- The Central Pacific Drive: Nimitz taking the Gilberts, the Marshalls, and the Marianas. This was "Big Blue Blanket" carrier warfare.

These two paths eventually converged on Okinawa and Iwo Jima. If you track this on a map, it looks like a giant pair of pincers closing in on the Japanese home islands.

The Maps They Didn't Show You

Cartography in the 1940s was a weapon. We often think of maps as objective, but they’re always biased. The Japanese maps of the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" made the Pacific look like a unified lake, a cohesive empire. American maps often used "Polar Projections" or "Mercator Projections" that distorted the size of the islands to make them look more significant than they were.

There's also the issue of bathymetry—the map of what's under the water. Submarine warfare was arguably the most effective part of the US strategy. By 1944, US subs had effectively cut off Japan from its colonies. If you look at a map of Japanese merchant ship sinkings, the dots cluster around the Luzon Strait and the coast of China. It’s a map of a country being strangled.

Honestly, the "real" war map isn't just where the troops were; it’s where the fuel was. Without oil from the East Indies, the Japanese fleet was stuck in port. By the end of the war, the war in pacific map showed a Japan that was a literal island in every sense—isolated, starving, and out of options.

Misconceptions About the Terrain

People think "Pacific" and they think "tropical paradise."

Wrong.

The map doesn't show you the humidity. It doesn't show the volcanic ash of Iwo Jima that was like walking through a bowl of flour. It doesn't show the "razor coral" of Tarawa that shredded boots and skin.

🔗 Read more: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

A major mistake people make when reading a war in pacific map is assuming the scale of the islands matches their strategic importance. Peleliu is tiny. It's a dot. Yet, the battle there was one of the most lopsidedly violent encounters of the war. The map tells you where people died, but it doesn't always tell you why that specific rock mattered. Usually, it was for one thing: a 5,000-foot strip of flat land where you could land a B-29.

The Legacy of the Lines

Even today, the war in pacific map dictates modern geopolitics. The "First Island Chain" that military analysts talk about today when discussing China? That’s the same geography. The bases we have in Guam and Okinawa? Those are legacies of the 1945 map.

We are still living in the footprint of the Pacific War.

If you want to truly understand this geography, don't just look at a static image. You have to look at the logistical lines. You have to realize that every bullet, every tin of Spam, and every gallon of aviation fuel had to be shipped across thousands of miles of submarine-infested water. The map was a logistical miracle as much as it was a tactical one.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you’re trying to study the war in pacific map for a project, a game, or just personal interest, don't rely on a single source. History is 3D.

- Check out the West Point Military Academy digital archives. They have the most accurate situational maps that show troop movements day-by-day.

- Compare "Area" vs "Point" maps. Area maps show who "owned" what, but point maps show where the actual bases were. In the Pacific, you only really controlled the 10 miles around your airfield. Everything else was empty ocean.

- Use Google Earth. Turn on the 3D terrain and look at the "atolls." An atoll isn't a solid island; it's a ring of coral around a lagoon. Understanding that explains why landings were so difficult—ships couldn't get over the reef.

- Read "The Fleet at Flood Tide" by James D. Hornfischer. He does an incredible job of explaining how the Marianas campaign changed the map forever by bringing Japan within range of the B-29 bombers.

The Pacific wasn't just a place where a war happened. The geography was the war. Every mile gained was a victory over the sheer scale of the planet. When you look at that war in pacific map next time, remember the empty space. That's where the real story lives.