Walk down East Bay Street today and you’re mostly looking for a good cocktail or a view of the harbor. It’s breezy. It’s peaceful. But three centuries ago, you would have been standing on top of a massive brick wall, likely sweating through a wool coat and eyeing the horizon for Spanish warships or literal pirates.

Most people visiting South Carolina think of the "Holy City" as a place of church steeples and pastel houses. That's the postcard version. The grit is underneath. For a few decades in the late 1600s and early 1700s, this place was the Walled City of Charles Town, the only English walled city in North America. It wasn't built for aesthetics. It was built because the settlers were terrified.

Honestly, they had every reason to be. Between the Yamasee War, Blackbeard’s blockade, and the ever-present threat of a Spanish fleet sailing up from St. Augustine, the early Carolinians lived in a pressure cooker.

A City Built on a Swamp and a Prayer

The original 1670 settlement at Albemarle Point (now Charles Towne Landing) was a bit of a disaster. It was buggy and hard to defend. By 1680, they moved the whole operation to "Oyster Point," the peninsula where the Ashley and Cooper Rivers meet. This was the birth of the Walled City of Charles Town.

They didn't just build houses; they built a perimeter.

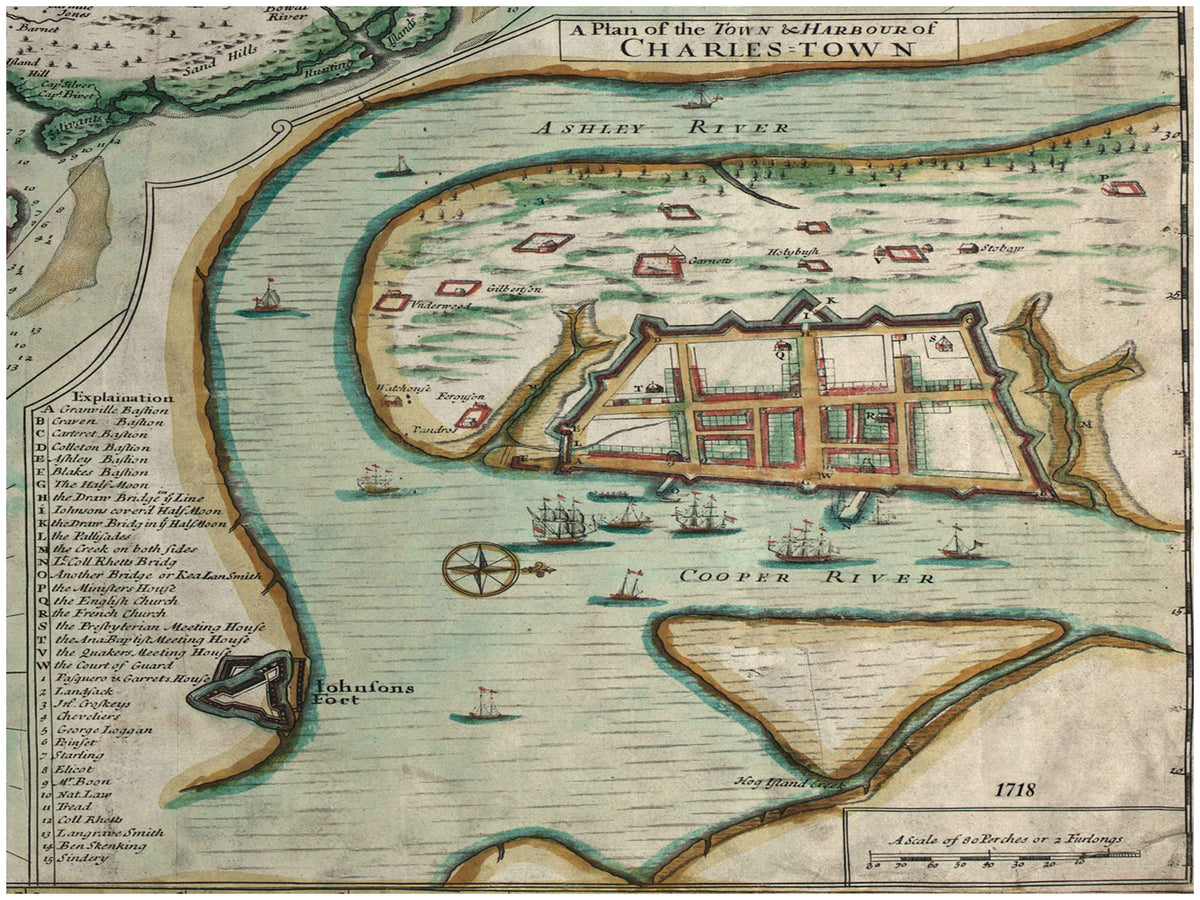

By the early 1700s, specifically around 1704, the fortification plan was in full swing. We’re talking about a massive enclosure that covered roughly 62 acres. It wasn't a castle like you’d see in Europe. It was a sophisticated system of "bastions" (those diamond-shaped projections) and "curtain walls."

If you look at the famous 1711 Crisp Map—which is basically the Rosetta Stone for Charleston archaeologists—you see a city that looks more like a military outpost than a colonial capital. You had the Granville Bastion on the south end (near where Missroon House stands today) and the Craven Bastion on the north. In between? A lot of brick, palmetto logs, and cannons.

🔗 Read more: UNESCO World Heritage Places: What Most People Get Wrong About These Landmarks

The wall on the waterfront side was the "Curtain Wall." It was made of brick and stood about four to five feet high, designed to stop a naval invasion. On the landward side, things were even more intense. Since they didn't have enough brick for the whole thing, they used earthworks—massive dirt mounds—and a "moat" or "fosse."

Imagine a 10-foot-deep ditch filled with stagnant, brackish water. It was disgusting. It was a breeding ground for mosquitoes. But it kept the cavalry out.

Why the Walls Eventually Came Down

Walls are great for defense, but they're terrible for business. By the 1720s and 30s, the Walled City of Charles Town was bursting at the seams. The population was exploding because of the rice and indigo trade. Merchants wanted to build wharves. They wanted their warehouses right on the water, not behind a pile of dirt and brick.

The walls started to feel like a cage.

Once the immediate threat of Spanish invasion faded and the "Golden Age of Piracy" was effectively ended with the hanging of Stede Bonnet in 1718, the walls became an expensive nuisance. Maintenance was a nightmare. The salt air ate the mortar. The humid South Carolina climate turned the wooden supports into mush.

Piece by piece, the city literally ate its own defenses. They used the old bricks to pave streets or as fill for new construction. By the time the Revolutionary War rolled around, much of the original wall was gone, though the British and Americans would later build new, temporary fortifications.

💡 You might also like: Tipos de cangrejos de mar: Lo que nadie te cuenta sobre estos bichos

Finding the Ghost of the Wall Today

You can't see the wall when you're walking to dinner, but it’s there.

Archaeologists, particularly the team led by Martha Zierden at the Charleston Museum, have spent decades playing a high-stakes game of "Where’s the Wall?" Every time a utility company digs a hole in the street, there’s a chance they hit a 300-year-old brick foundation.

The most famous remnant is in the basement of the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon. If you go down there, you can see a large section of the Half-Moon Battery. It’s cold, damp, and smells like old stone. It’s the real deal. This was the centerpiece of the city’s harbor defense. Standing there gives you a weird sense of scale—you realize just how small and vulnerable the original settlement actually was.

Other traces are subtle:

- Adger’s Wharf: Parts of the old low battery walls are built right over the original fortifications.

- Tradd Street: The "Redan" or small triangular fortifications once stood near the intersections here.

- The Street Grid: Ever wonder why the streets in the French Quarter are so narrow and cramped? They were designed to fit inside that 62-acre box.

Basically, the "Walled City" footprint defined the DNA of downtown Charleston. The reason the city is so walkable today isn't urban planning—it's because nobody wanted to walk further than they had to when there were pirates outside the gate.

The Misconception of "Perfect" Defense

People often think these walls made the city an impenetrable fortress. They didn't.

📖 Related: The Rees Hotel Luxury Apartments & Lakeside Residences: Why This Spot Still Wins Queenstown

During the Siege of Charleston in 1780, the city fell to the British. The walls—or what was left of them—weren't enough. The real defense of the city was always more about the geography of the harbor and the treacherous sandbars that grounded enemy ships. The walls were a psychological barrier as much as a physical one. They told the world: "We are here, we are English, and we aren't leaving."

It's also worth noting that the walls weren't just about foreign invaders. They were about control. In a colony where the enslaved population would soon outnumber the free population, the walls served as a tool of internal surveillance and "security."

How to Experience the Walled City Now

If you want to actually "see" the Walled City of Charles Town, don't just look for bricks. Look for the shifts in elevation.

- The Powder Magazine: This is the oldest public building in South Carolina (built around 1713). It sat just inside the city walls. It was tucked away so that if the gunpowder exploded, it wouldn't take the whole waterfront with it. It's a museum now, and it’s one of the best places to see the actual equipment used to defend the wall.

- The Charleston Museum: They have a dedicated exhibit on the "Walled City" that features artifacts pulled directly from the excavations. You’ll see everything from cannonballs to the remains of the wine bottles the soldiers were drinking while on watch.

- Walk the Perimeter: Start at the Old Exchange, walk south to the site of the Granville Bastion (near 40 East Bay St), then head west toward Meeting Street, and loop back north. You’ve just circled the heart of the 1704 defenses.

Actionable Steps for the History-Minded Traveler

Don't just take a generic carriage tour. If you want the real story of the Walled City of Charles Town, follow this checklist:

- Visit the Old Exchange first. Do the dungeon tour. Seeing the physical bricks of the Half-Moon Battery is essential for context.

- Download the "Walled City" maps. The Mayor’s Walled City Task Force has done incredible work mapping the exact coordinates of the bastions. You can overlay these on your phone while walking.

- Check for "Active Digs." Sometimes, the Charleston Museum has ongoing excavations near the waterfront. If you see archaeologists in a hole near East Bay, stop and look.

- Look for the Plaques. There are small markers embedded in the sidewalks and on buildings that indicate where the bastions used to sit. Most people walk right over them.

- Go to the Powder Magazine. It’s the most tactile way to understand the military reality of 18th-century life.

The walls are gone, but they dictated the shape of every street, alley, and garden you see in the historic district today. Charleston isn't just a city with a history; it’s a city built on top of a fortress that refused to disappear.