October 1929 didn't just happen. It wasn't some random lightning bolt from a clear blue sky, even if the bankers on Wall Street at the time tried to pretend it was.

People think everyone lost their shirts in a single afternoon. They didn't. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 was actually a slow-motion car wreck that took weeks to fully ignite and years to finish its path of destruction.

Honestly, the "Roaring Twenties" were a bit of a fever dream. You had World War I veterans coming home, new technologies like the radio and the toaster hitting shelves, and a stock market that seemed like a literal money printer. By 1929, roughly 10% of American households were invested in the market. That sounds small now, but back then? It was massive. Everyone from your barber to your grandmother was checking the ticker tape.

But beneath the jazz and the gin, the foundation was rotting.

Why the Wall Street Crash of 1929 was basically inevitable

The problem wasn't just that prices were high; it was how people were paying for them. Enter: "buying on margin."

Imagine you want to buy $1,000 worth of stock. You only have $100. In 1928, a broker would happily lend you the other $900. It felt like free money as long as the market went up. But if the stock dropped? The broker would call in that loan immediately. You had to pay up right then, or they’d sell your stock for a loss.

This created a domino effect. When the first few bricks wobbled, the whole wall came down because everyone was forced to sell at once to cover their debts.

Economists like John Kenneth Galbraith, who wrote the definitive The Great Crash, 1929, pointed out that the economy was wildly top-heavy. The rich were getting much richer, but the average worker's wages weren't keeping up. People were buying cars and radios on credit. Sound familiar? By mid-1929, production was slowing down. Steel production dropped. Car sales slumped. The "smart money" started heading for the exits in September, but the general public was still buying the dip.

Black Thursday and the Illusion of Safety

October 24, 1929. Black Thursday.

✨ Don't miss: Funny Team Work Images: Why Your Office Slack Channel Is Obsessed With Them

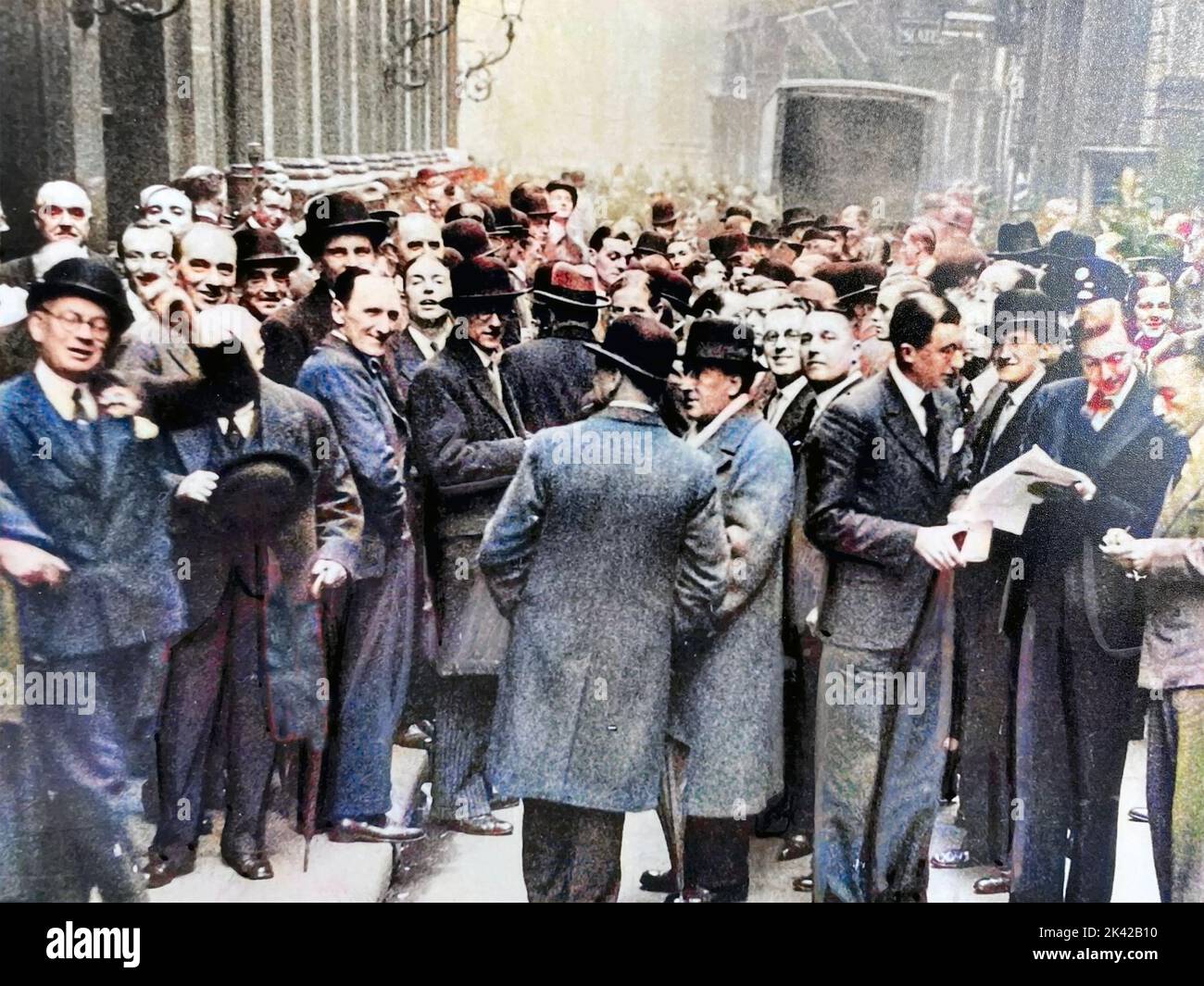

The morning started with a localized panic. Prices gapped down. By midday, the floor of the New York Stock Exchange was a mosh pit of screaming men in wool suits. There’s a famous story about Richard Whitney, the Vice President of the Exchange. He walked onto the floor and loudly placed a massive order for U.S. Steel at a price well above the current market.

He was trying to show confidence. He was acting on behalf of a group of bankers, including titans from J.P. Morgan, who pooled their cash to prop up the market.

It worked. For a few days.

The market stabilized on Friday and Saturday. People breathed a sigh of relief. They thought the "organized support" of the big banks had saved the day. But the weekend gave investors too much time to think. They realized the bankers couldn't hold back the tide forever. When the opening bell rang on Black Monday (October 28), the bottom fell out. Then came Black Tuesday.

On October 29, the volume was so high—16.4 million shares—that the ticker tape machines couldn't keep up. They were hours behind. Investors were selling stocks without even knowing what the current price was. They just wanted out.

The Myth of the Jumpers

We've all heard the stories about bankers jumping out of skyscrapers the moment the market crashed. It’s mostly a legend.

While there were certainly tragic suicides—the head of Rochester Gas and Electric, for instance—the "suicide wave" was largely an exaggeration by the press. The New York Chief Medical Examiner actually noted that the suicide rate in the months following the crash was lower than it had been in the summer.

The real tragedy wasn't a sudden leap from a window; it was the slow, grinding poverty that followed. It was the "Hoovervilles" (shanty towns) popping up in Central Park. It was the fact that by 1933, nearly 25% of the country was unemployed.

🔗 Read more: Mississippi Taxpayer Access Point: How to Use TAP Without the Headache

It wasn't just a "Stock Market" Problem

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 didn't cause the Great Depression all by itself, but it was the catalyst that exposed every single weakness in the American banking system.

Back then, banks weren't the giants we see today. They were small, local, and unregulated. Many of them had used their depositors' savings to gamble on the stock market. When the market crashed, the banks lost that money.

When people realized their life savings might be gone, they ran to the banks to withdraw their cash. This is a "bank run." Since banks only keep a fraction of their cash on hand, they ran out of money and locked their doors. Over 9,000 banks failed in the 1930s. If your bank closed, your money was just... gone. No FDIC insurance. No bailouts for the little guy.

The Global Aftershocks

This wasn't just an American disaster. Because of the gold standard and the web of debts left over from WWI, the crash exported misery to Europe.

Germany, already struggling with hyperinflation and reparations, saw its economy collapse. This economic desperation is widely cited by historians as the fertile ground that allowed the Nazi party to rise to power. The crash essentially ended the first era of globalization. Countries retreated into protectionism, passing things like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which basically strangled international trade.

It’s a grim reminder that when the world's largest financial engine throws a rod, everyone gets hit by the shrapnel.

Can it happen again?

Yes and no.

We have "circuit breakers" now. If the S&P 500 drops 7% in a single day, the New York Stock Exchange literally hits a pause button for 15 minutes to let people cool off. If it drops 20%, they shut it down for the day. We also have the FDIC, so if your bank fails, your money (up to $250k) is safe.

💡 You might also like: 60 Pounds to USD: Why the Rate You See Isn't Always the Rate You Get

But the core psychological driver of the Wall Street Crash of 1929—irrational exuberance followed by blind panic—is part of human DNA. We saw echoes of it in 1987, 2008, and even the "flash crashes" of the 2020s. The math changes, the technology gets faster, but the fear remains the same.

Leverage is still the monster under the bed. Whether it's subprime mortgages or high-frequency trading algorithms, the moment people start trading with money they don't actually have, the risk of a 1929-style "forced liquidation" sky-rockets.

Lessons from the Rubble

So, what do we actually do with this history? It’s not just a trivia session.

First, understand that the "all-time high" is the most dangerous time to get cocky. In September 1929, the famous economist Irving Fisher famously said stock prices had reached "what looks like a permanently high plateau." He was wrong. Spectacularly wrong. He lost his personal fortune and his reputation.

Second, diversification isn't just a buzzword. In 1929, if you were all-in on RCA (the "Nvidia" of its time), you were wiped out. Those who had cash, gold, or even just a mix of different assets survived to buy at the bottom.

Third, look at the "margin" in your own life. Not just financial margin, but emotional and temporal. The crash was a crisis of liquidity—people needed cash now and didn't have it. Keeping an emergency fund isn't just about car repairs; it's about not being forced to sell your assets when the world is on fire.

To protect yourself from the echoes of 1929, take these specific steps:

- Audit your leverage. Check your brokerage accounts to see if you are trading on margin. If the market dropped 20% tomorrow, would you face a margin call? If yes, de-risk immediately.

- Verify your "Safe" cash. Ensure your bank is FDIC insured (or NCUA for credit unions). Avoid keeping significant life savings in "shadow banking" platforms or unregulated crypto exchanges that lack these protections.

- Study the Ticker. Don't just look at the price of stocks. Look at the volume. The 1929 crash was defined by a total lack of buyers. If you see prices falling on high volume, it’s a sign of a structural shift, not just a "dip" to be bought.

- Read the primary sources. Pick up a copy of Lords of Finance by Liaquat Ahamed. It explains how the central bankers of the time—the "four horsemen"—actually caused more damage by trying to fix things with old-school logic that no longer applied to a modern world.

The market eventually recovered, but it took until 1954 for the Dow Jones to reach its September 1929 peak again. That's 25 years. Patience is a virtue, but survival is the prerequisite for playing the game.