Look at your thumb. Now, imagine everything you've ever known—every war, every first kiss, every cup of coffee, and every person who ever lived—is smaller than a single pixel on a grainy TV screen. That isn't a metaphor. It’s a reality captured in the Voyager 1 photo of Earth, a grainy, streaked image that almost didn't happen.

Carl Sagan had to beg.

NASA didn't want to do it. The engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) were actually pretty worried that pointing the camera back toward the Sun would fry the sensitive Vidicon cameras. They’d already finished the primary mission at Jupiter and Saturn. Voyager 1 was speeding out of the solar system at roughly 40,000 miles per hour. It was 3.7 billion miles away. Why risk the hardware for a photo of nothing?

Sagan pushed. He knew the value wasn't scientific. It was perspective. Eventually, after years of back-and-forth, NASA Administrator Richard Truly gave the green light. On February 14, 1990, the spacecraft turned its neck and took one last look home.

Why the Voyager 1 Photo of Earth Looks So Strange

If you look at the raw image, it’s a mess. There are these weird vertical bands of light cutting across the frame. People often think those are laser beams or some cosmic phenomenon. They aren’t. They’re just sunbeams. Specifically, they are artifacts caused by sunlight scattering inside the camera's optics because the craft was positioned so close to the Sun from that distance.

Earth is a speck.

It’s about 0.12 pixels in size. It’s caught in one of those scattered light rays, appearing as a tiny, flickering point of blue-white light. When the data finally trickled back to Earth—taking about five and a half hours to travel across the vacuum at the speed of light—it arrived as a series of 1s and 0s that had to be reconstructed. The final product we see today is often a composite of three different filters: blue, green, and violet.

The technical specs are wild when you think about 1990 tech. The camera used a slow-scan vidicon tube. This wasn't a digital sensor like the one in your iPhone. It was more like a television camera from the 70s. Because the light was so faint from nearly 4 billion miles away, the exposure time had to be exactly right. Too long, and the Sun would wash everything out. Too short, and Earth would vanish into the blackness.

💡 You might also like: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

The Logistics of a 4-Billion-Mile Selfie

Space is empty. Really empty.

To get the Voyager 1 photo of Earth, the imaging team had to program the spacecraft weeks in advance. Remember, there’s no joystick. You send a command, wait hours for it to arrive, and hope the gyroscopes and thrusters behave. Voyager was headed "up" out of the ecliptic plane, the flat disk where most planets live. This gave it a "birds-eye" view of the neighborhood.

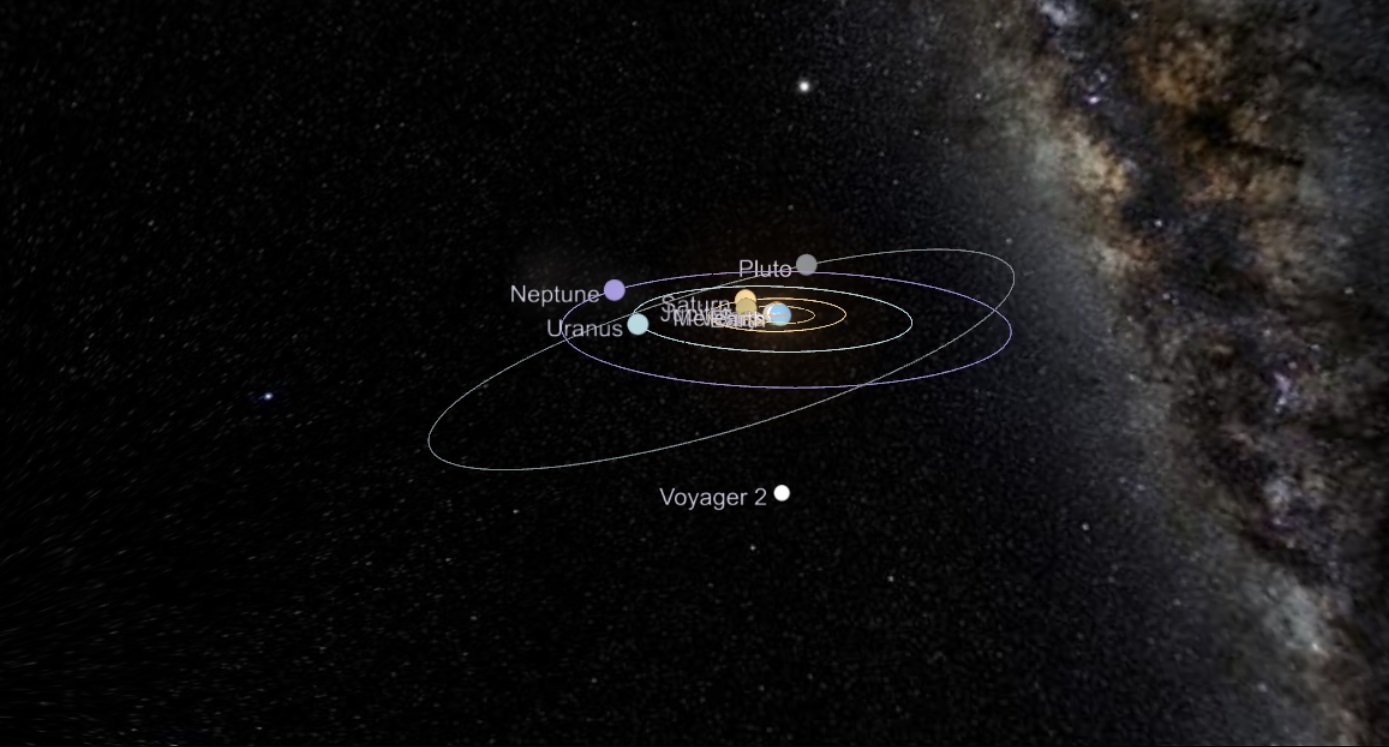

Candice Hansen-Koharcheck and Carolyn Porco were two of the key scientists involved in planning this "Solar System Family Portrait." It wasn't just Earth. Voyager took 60 frames in total, capturing Neptune, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, and Uranus. Mercury was too close to the Sun to see. Mars was lost in the glare. Pluto (still a planet then!) was too small and faint to be picked up.

The "Pale Blue Dot" Monologue

You can't talk about this photo without Carl Sagan’s 1994 book. He coined the term "Pale Blue Dot." He noted that from this distant vantage point, Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But to us, it’s everything.

Sagan wrote: “That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.”

It’s a bit of a gut punch. Honestly, it’s the most successful piece of "science PR" in history because it shifted the conversation from "how much does this rocket cost?" to "who are we in the universe?"

Debunking the Myths About the Image

A lot of folks get the details wrong. No, this wasn't the first photo of Earth from space. That happened way back in 1946 using a V-2 rocket. And it’s not the most detailed—the "Blue Marble" from Apollo 17 holds that title.

📖 Related: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

What makes this one different is the scale.

- Myth 1: Voyager 1 stopped to take the photo. Reality: It was hauling. The cameras were fired while the craft was in motion, but because the planets are so far away, there was no motion blur.

- Myth 2: The photo was released immediately. Reality: It took months to process the data and create the mosaic. It wasn't unveiled to the public until a press conference in May 1990.

- Myth 3: You can see the moon. Reality: Not in the famous single frame of the Pale Blue Dot. The moon and Earth are essentially merged into one tiny point of light at that resolution.

The Tech Specs: A Relic in the Void

The computer onboard Voyager 1 has less memory than the key fob for your car. It has about 68 kilobytes of memory. Total.

The data rate for the Voyager 1 photo of Earth was painfully slow. By the time it was at that distance, it was transmitting at about 1.4 kilobits per second. For context, a basic modern webpage is several megabytes. It took forever to get those pixels home.

The cameras were actually turned off shortly after this sequence was finished. Why? To save power and memory for the interstellar mission. Voyager 1 is currently in interstellar space—the space between stars. It is no longer "seeing" anything. It is feeling its way through the dark using instruments that measure magnetic fields, cosmic rays, and plasma densities.

The cameras will never be turned back on. The heaters for them have been shut down to keep the core instruments running. They are frozen, dead eyes staring into the vacuum.

Is there a "New" Pale Blue Dot?

We’ve tried to recreate the magic. Voyager 2 didn't take a similar photo because of its trajectory. However, the Cassini spacecraft took a photo of Earth through the rings of Saturn in 2013. It’s called "The Day the Earth Smiled." It’s much higher resolution, much prettier, and much more "modern."

But it doesn't hit the same way.

👉 See also: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

There’s something about the 1990 version. The graininess makes it feel more real. It feels like a grainy home movie of a childhood you can't go back to. It captures the isolation of our planet in a way that high-def digital photography actually struggles to do.

In 2020, for the 30th anniversary, NASA JPL processed the image again using modern image-processing software. They cleaned up some of the noise while being careful to keep the "integrity" of the original data. This version is much clearer, but Earth remains exactly what it was: a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark.

The Reality of Our Cosmic Neighborhood

When you look at the Voyager 1 photo of Earth, you're seeing the limits of our reach. We are a "Type 0" civilization on the Kardashev scale. We haven't even mastered our own star’s energy, let alone traveled to the next one.

Voyager 1 is currently about 15 billion miles away. That sounds like a lot. But in galactic terms? It’s basically still in our front yard. It will take another 40,000 years for it to pass within 1.6 light-years of the star AC +79 3888 in the constellation Camelopardalis.

Space is big. You just won't believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. The photo is the only thing that makes that scale digestible for a human brain.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to really "feel" the impact of this image, don't just look at a tiny version on your phone.

- Find the high-resolution 30th-anniversary remaster. NASA's JPL website hosts the full-size TIFF files. Download it.

- Zoom in. Keep zooming until the Earth is just those few pixels. Look at the vastness of the black space surrounding it.

- Read the full "Pale Blue Dot" speech. It’s not long, but it’s probably the most important piece of literature ever written by a scientist. It changes how you view your daily stresses.

- Track the Voyager. There is a real-time "Eyes on the Solar System" tool by NASA that shows exactly where Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are right now, their speed, and which instruments are still alive.

The Voyager 1 photo of Earth wasn't a scientific necessity. It was a philosophical one. It remains a reminder that for all our differences, we are all stuck on the same tiny, fragile raft in a very big ocean.

If we don't take care of this pixel, there isn't another one waiting for us. Not yet, anyway. We’re still just the people on the dot.