When most people think about the voyage of the Beagle, they picture a white-bearded Charles Darwin sitting on a giant tortoise in the Galápagos, instantly figuring out how evolution works. It's a clean, simple story. It’s also mostly wrong.

The real trip was a five-year slog. It was messy. Darwin spent most of it being incredibly seasick and wishing he was back in England. Honestly, he wasn't even supposed to be the "naturalist" in the way we think of it today; he was technically a dining companion for the captain, Robert FitzRoy, a man who was terrified of going insane from loneliness.

What actually happened between 1831 and 1836 wasn't a "eureka" moment. It was a slow-burn realization built on thousands of miles of trekking through South American jungles, surviving earthquakes, and shipping crates of dead birds back to London. If you've ever felt like your career or your big project is moving at a snail's pace, Darwin’s journey is the ultimate proof that revolutionary ideas take time—and a lot of grunt work.

A Mission for Maps, Not Monkeys

We have this tendency to think the British Admiralty sent a ship across the world just to help a 22-year-old dropout find himself. They didn’t. The HMS Beagle was on a cold, hard military and commercial mission: mapping the coastline of South America.

The British Empire needed better charts. Better charts meant safer trade routes.

Captain FitzRoy was a brilliant, albeit high-strung, hydrographer. He needed someone of his own social "class" to talk to so he wouldn't crack under the pressure of command. Enter Darwin. Darwin was a Cambridge graduate who had spent more time collecting beetles and hunting than studying for the clergy. He was a last-minute choice. In fact, FitzRoy almost rejected him because he thought the shape of Darwin’s nose indicated a lack of "determination."

Talk about a close call.

They left Plymouth on December 27, 1831. It was a 90-foot ship with 74 people crammed into it. Space was a luxury nobody had. Darwin slept in a hammock slung over his drafting table in the chart room. Every time he stood up, he bumped his head. For five years.

The Myth of the Galápagos "Aha!" Moment

If you search for the voyage of the Beagle online, you'll see the Galápagos Islands mentioned in every second sentence. But here’s the kicker: Darwin was only there for about five weeks out of a five-year trip.

And he kind of blew it while he was there.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

He didn't even realize the finches were all different species at first. He thought some were grosbeaks and others were wrens. He didn't even bother to label which island each bird came from—a massive scientific no-no that he had to fix later by begging his shipmates for their notes.

The real heavy lifting happened in South America.

He spent years riding with Gauchos in Argentina. He dug up fossils of giant ground sloths (Megatherium) and armored Glyptodons that looked like Volkswagens made of bone. This was the turning point. Seeing these massive, extinct creatures that looked like giant versions of the tiny armadillos he was currently eating for dinner made him wonder: why would one disappear and the other stay?

It wasn't a lightning bolt. It was a nagging itch in the back of his brain.

Living through the Chilean Earthquake of 1835

In February 1835, Darwin was lying in a forest near Valdivia, Chile, when the ground started to move. It wasn't just a tremor; it was a massive 8.5 magnitude earthquake.

It changed everything for him.

When he got to the coast, he saw that the land had literally been shoved upward. Mussel beds were rotting in the sun, three or four feet above the high-tide mark where they used to live.

This was the "proof" he needed for the theories of Charles Lyell, a geologist who argued that the Earth was shaped by tiny changes over vast amounts of time. Darwin realized that if the Earth could move up a few feet in a minute, then over millions of years, mountains could grow. And if the Earth changed, the animals living on it had to change too. Otherwise, they'd just die.

It’s easy to forget that Darwin was a geologist first. The biology came later.

✨ Don't miss: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

Life on a Small Ship

The Beagle wasn't a luxury cruise. It was wet, cramped, and smelled like old wood and salted pork. Darwin and FitzRoy got along well enough, but they had "religious" arguments that occasionally led to FitzRoy banning Darwin from his table.

FitzRoy was a literalist. He believed the Earth was young and the Bible was a history book. Darwin was seeing evidence that suggested the world was ancient.

- Seasickness: Darwin was miserable at sea. He spent weeks horizontal in his hammock.

- The Library: They had about 400 books on board. This was Darwin’s real education.

- Correspondence: He wrote thousands of pages of letters. By the time he got home, he was already a scientific celebrity because his mentors in England had been reading his reports to the Geological Society.

The Australian Disappointment

By the time the Beagle hit Australia in 1836, Darwin was ready to go home. He wasn't even that impressed with the "strangeness" of the wildlife. He famously wrote that an unbeliever might think two different Creators had been at work because the animals were so weirdly different from those in the rest of the world.

He saw a platypus and thought it was neat, but he was mostly bored. He found the Australian bush "uninviting" and the people too focused on money.

It goes to show that even one of history's greatest minds had "off" days where he just wanted a decent cup of English tea and a bed that didn't rock.

The Aftermath: Why It Still Matters

When the Beagle finally docked in Falmouth in October 1836, Darwin didn't publish On the Origin of Species the next week. It took him twenty years to work up the nerve.

He spent that time obsessing over barnacles. Seriously. Eight years on barnacles.

But the voyage of the Beagle provided the raw data. It gave him the "vibe" of the natural world—the brutality, the beauty, and the sheer scale of time. He didn't just invent a theory; he observed it into existence.

Today, we use his findings to understand everything from antibiotic resistance to how climate change will shift animal migrations. It’s the foundation of modern biology. Without that 90-foot ship and a captain with a temper, we’d still be scratching our heads about why fossils exist.

🔗 Read more: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

Actionable Takeaways from Darwin's Journey

Darwin's trip wasn't just a scientific expedition; it was a masterclass in how to process information and build a legacy. If you're looking to apply his "Beagle Method" to your own work or life, here is how you do it:

1. Collect first, conclude later

Darwin didn't start with a theory of evolution. He started by picking up rocks and shooting birds. He gathered data for years before he allowed himself to form a major hypothesis. In our world of "hot takes," there is immense value in just observing for a while before deciding what it all means.

2. Seek out the "Anomalies"

Most people would have ignored the different beaks on those finches or the slight variations in tortoise shells. Darwin obsessed over them. If you see something in your field that doesn't quite fit the standard narrative, don't ignore it. That's usually where the breakthrough is hiding.

3. Cross-pollinate your interests

Darwin’s breakthrough happened because he applied geology (the Earth moves) to biology (life changes). If you only read books in your specific niche, you’re missing the bigger picture. Read outside your comfort zone.

4. Documentation is everything

Darwin kept meticulous journals. He wrote letters. He drew sketches. Ideas are slippery; if you don't write them down the moment they happen—even if they seem small—they disappear.

5. Embrace the "Slog"

He spent years doing the boring stuff—labeling jars, cleaning fossils, and dealing with nausea. Success is rarely a straight line of "wins." It’s mostly just showing up and doing the work when you’d rather be doing literally anything else.

If you want to see the actual specimens Darwin brought back, the Natural History Museum in London is the place to go. They still have some of his finches. Just remember when you look at them: the guy who caught them had no idea they would change the world. He was just a kid on a boat trying not to throw up.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

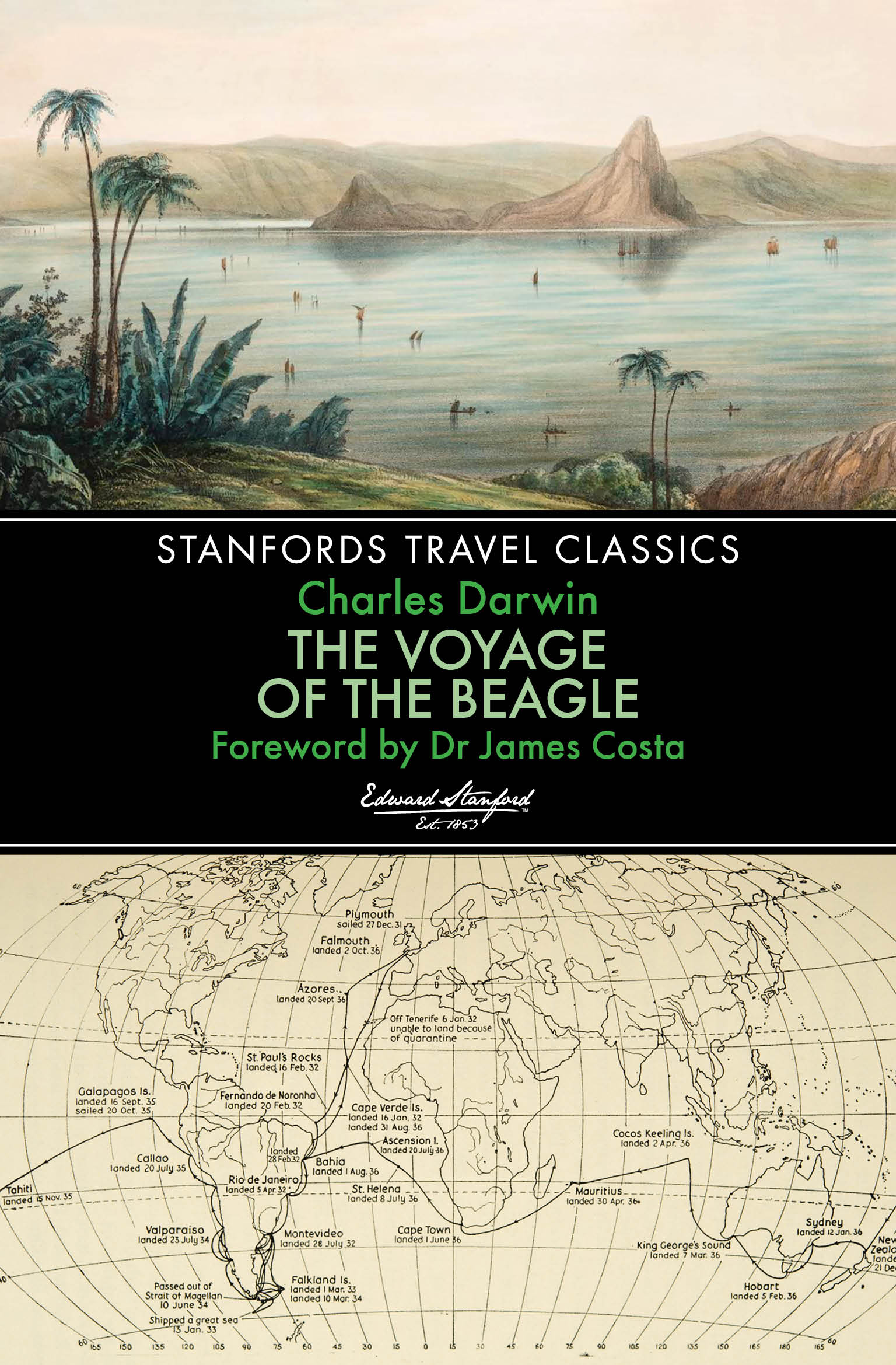

- Read the Source Material: Pick up a copy of The Voyage of the Beagle. It’s actually a very readable travelogue, full of adventure stories and descriptions of the Wild West-era of South America.

- Trace the Route: Use tools like Google Earth to follow the Beagle’s path from the Cape Verde Islands down to Tierra del Fuego. Seeing the terrain helps explain why the trip took five years.

- Investigate the Wallace Connection: Look into Alfred Russel Wallace, the man who came up with the same idea as Darwin at the same time. It adds a whole new layer of drama to the story.