Ever tried to compress a gallon of water? You can't. Not really. Liquids are stubborn. But gases? Gases are basically the introverts of the molecular world—they just want as much space as possible between themselves and everyone else. Because of that, the volume of gases is one of the most unpredictable, fascinating, and honestly, slightly annoying things to measure in a lab.

Most people think volume is just about the size of the container. That’s only half the story. If you take a tank of oxygen from a cold room into a hot garage, that gas is going to try its hardest to expand or it's going to spike the pressure until something gives. It’s a constant dance between temperature, pressure, and the number of molecules you're shoving into a space.

Why Gases Behave Like Empty Space

Think about a solid block of iron. The atoms are packed like commuters on a rush-hour subway in Tokyo. There’s nowhere to go. Now, think about a gas. If those iron atoms were a gas, they’d be miles apart. In fact, in a typical sample of air, the actual "stuff"—the physical matter of the molecules—occupies less than 0.1% of the total volume. The rest? Just empty, lonely space.

This is why the volume of gases is so sensitive. Since there's so much "room to move," any change in the environment sends the molecules flying faster or slower, which changes how much space they take up. This isn't just theory. It’s why bags of chips puff up when you drive into the mountains. The air pressure outside the bag drops, so the gas inside pushes out to claim more volume.

The Ideal Gas Law: A Beautiful Lie

If you’ve spent five minutes in a chemistry class, you’ve heard of $PV = nRT$. It’s the "Ideal Gas Law." It’s the holy grail for calculating the volume of gases.

- P is pressure.

- V is volume.

- n is the amount of gas (moles).

- R is the universal gas constant (about 0.0821 if you’re using atmospheres).

- T is temperature (and it must be in Kelvin, or everything breaks).

But here’s the kicker: "Ideal" gases don't actually exist. The law assumes that gas molecules have zero volume themselves and that they don't attract or repel each other. In the real world, molecules like carbon dioxide or water vapor are "sticky." They have intermolecular forces. At high pressures or very low temperatures, the Ideal Gas Law falls apart. This is where engineers have to use the Van der Waals equation, which adds "correction factors" for the fact that molecules do, in fact, take up physical space and occasionally bump into each other with intent.

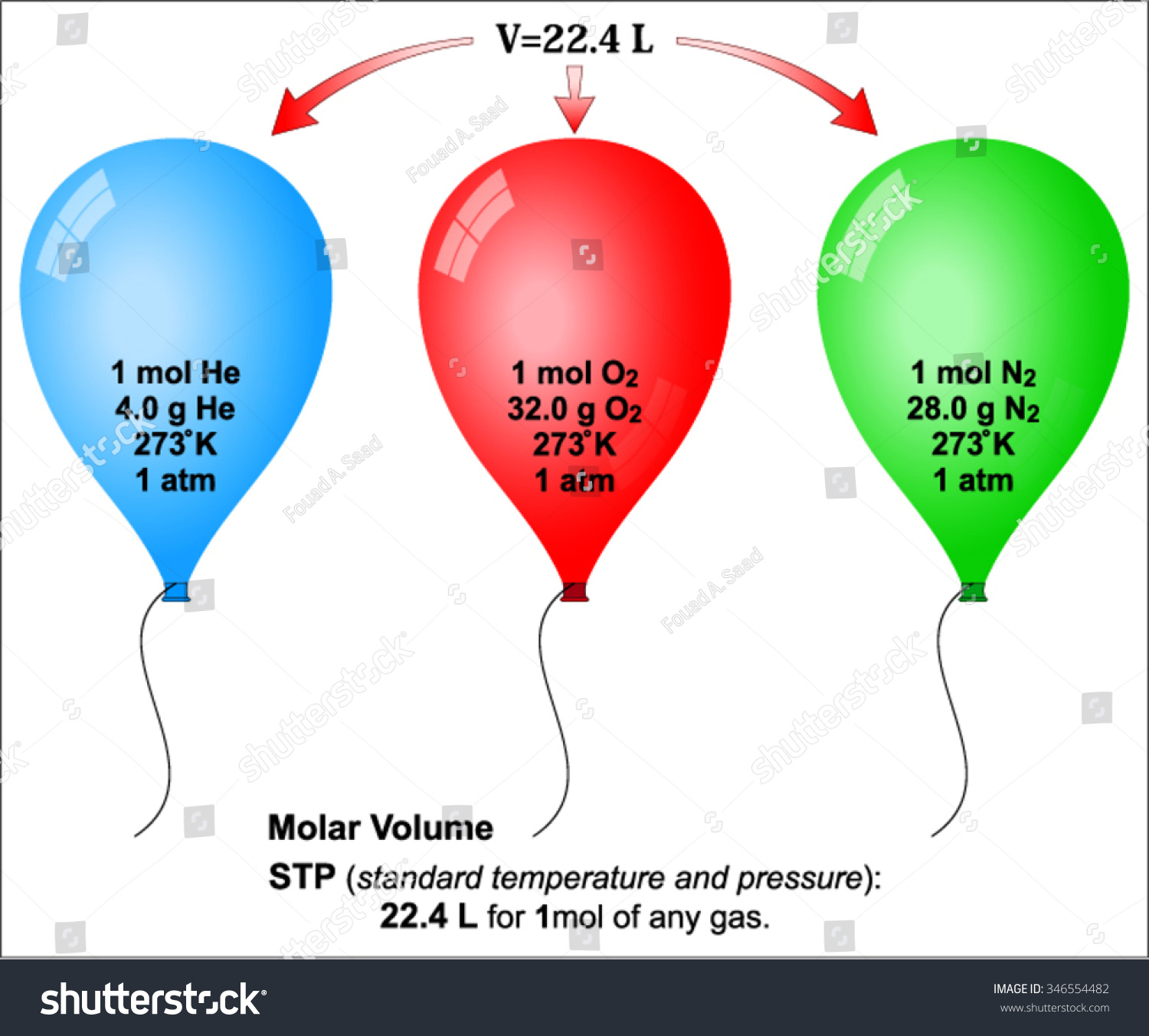

Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP)

To make sense of the volume of gases, scientists had to agree on a "neutral" baseline. They called it STP. Historically, this meant 0 degrees Celsius and 1 atmosphere of pressure. Under these specific conditions, one mole of any ideal gas occupies exactly 22.4 liters.

That’s roughly the size of a large beach ball.

It doesn’t matter if it’s light hydrogen or heavy xenon. If it’s one mole at STP, it takes up 22.4 liters. This is Avogadro’s Law in action. It’s incredibly counterintuitive. You’d think a "heavier" gas would be "bigger," right? Nope. Because the molecules are so far apart, their individual size is negligible compared to the space between them.

Charles’s Law and the Hot Air Balloon

If you heat a gas, it gets bigger. Jacques Charles figured this out in the 1780s, and it’s why hot air balloons stay off the ground. When you blast that propane burner, you aren't adding more air to the balloon. You're just making the existing air take up more volume.

As the temperature rises, the kinetic energy of the molecules spikes. They hit the sides of the balloon harder and more often, pushing the fabric outward. Because the same amount of gas is now spread over a larger volume, the air inside becomes less dense than the cool air outside. Buoyancy kicks in. Up you go.

👉 See also: TV Wall Mounts 75 Inch: What Most People Get Wrong Before Drilling

But there’s a limit. Absolute zero. That’s $-273.15$ degrees Celsius. Theoretically, at this temperature, the volume of gases would become zero. The molecules would simply stop moving. Of course, in reality, the gas would turn into a liquid or solid long before it hit that point, but the math behind it is what gave us the Kelvin scale.

Boyle’s Law: The Scuba Diver’s Nightmare

Robert Boyle was a bit of a polymath, and he spent a lot of time messing around with pressure pumps. He discovered an "inverse" relationship. If you double the pressure on a gas, you halve its volume.

This is life-or-death info for scuba divers.

If a diver takes a deep breath of air at 30 meters down (where the pressure is four times higher than the surface) and then swims to the top without exhaling, the volume of gases in their lungs will quadruple. Their lungs would literally rupture. This is why the golden rule of diving is: "Never hold your breath."

Real-World Applications: From Ammonia to SpaceX

Understanding the volume of gases isn't just for passing midterms. It’s the backbone of global industry. Take the Haber-Bosch process, which creates the ammonia used in fertilizer. This reaction involves nitrogen and hydrogen gases. To get the highest yield, engineers have to manipulate pressure and volume with extreme precision. Without this specific understanding of gas behavior, we couldn't feed half the planet’s population.

✨ Don't miss: Why It’s So Hard to Ban Female Hate Subs Once and for All

Then there’s rocketry. SpaceX’s Starship uses sub-cooled liquid methane and oxygen. Why sub-cooled? Because by lowering the temperature way below the boiling point, you increase the density and decrease the volume. This lets them cram more fuel into the same size tank, providing more thrust-to-weight ratio. It’s literally Charles’s Law in reverse to get more "bang" for the buck.

Common Misconceptions That Trip People Up

- "Gases always fill their container." Well, yes, but they don't do it evenly if there are extreme gravity or temperature gradients.

- "All gases weigh the same if the volume is the same." Absolutely not. A 22.4L balloon of Helium is much lighter than a 22.4L balloon of Radon. The volume is the same, but the mass is vastly different.

- "Humidity doesn't affect gas volume." It actually does. Water vapor is a gas, and it displaces other gases like nitrogen and oxygen. Moist air is actually less dense than dry air, which is why baseballs fly further in humid weather (less air resistance).

How to Measure Gas Volume Yourself

You don't need a multi-million dollar lab to see this in action. The most common way to measure the volume of gases produced in a chemical reaction is "displacement of water."

Basically, you fill a graduated cylinder with water and flip it upside down in a tub of water. You run a tube from your reaction (like baking soda and vinegar) into the mouth of the cylinder. As the $CO_2$ bubbles up, it pushes the water out. The amount of "empty" space at the top is your gas volume. Just remember to account for "vapor pressure"—a tiny bit of that volume is actually evaporated water, not your $CO_2$.

Actionable Takeaways for Working with Gases

If you're dealing with gas volumes in a DIY project, a home brewing setup, or a classroom, keep these specific steps in mind:

- Always convert to Kelvin. If you use Celsius in a gas calculation, your results will be wildly wrong because Celsius can be zero or negative, which breaks the ratios. Just add 273.15 to your Celsius reading.

- Check your pressure units. Standard pressure can be 101.3 kPa, 1 atm, or 760 mmHg. Mixing these up is the #1 cause of engineering errors in gas statics.

- Factor in "Real Gas" behavior. If you are working at pressures above 10 atmospheres or temperatures near the boiling point of the gas, stop using $PV=nRT$. Use a compressibility factor ($Z$) to account for the molecular stickiness.

- Account for altitude. If you're calibrating equipment in Denver versus Miami, the atmospheric pressure difference will change the volume of gases by about 20%.

Understanding gas volume is really about understanding that nothing is static. Gases are the most "alive" state of matter, constantly reacting to the world around them. Whether you're inflating a tire or designing a Martian habitat, the math stays the same: pressure, temperature, and volume are in a permanent tug-of-war.